The last two articles explored the development of three-dimensional perspective in Florence, but what about the cold North? Though Northern Europe lacked the Mediterranean’s clear sunbathed coasts, it had its own cultures and natural features which converged with each other and with the medieval heritage in ways that helped make three-dimensional perspective pan-European.

When Italian artists were perfecting linear relationships, northern painters advanced realism in their own ways. In the 1430s Jan van Eyck worked in another wealthy city of freedom-loving merchants, Bruges, which is in modern Belgium (Bruges, Ghent, and Ypres became wealthy from the cloth trade around 1100). He began to paint people’s features so that warts and wrinkles got as much attention as angelic Italian faces and sun-kissed beefcakes.

His Adoration of the Lamb in the Cathedral of St. Bavo in Ghent is a panoramic medieval view of the world with a northern flair. Processions of Old Testament patriarchs and prophets, New Testament figures, popes, bishops, deacons, and virgin martyrs arrive at an altar that’s surrounded by angels. A lamb symbolizing Christ stands on it, bleeding into a shiny chalice. Rolling verdant hills and cities with elaborate Gothic towers surround all the people. Van Eyck put everything into view to stress the theme’s universal importance. But to make this all-encompassing landscape real, he showed hundreds of plants and flowers in precise detail. Van Eyck set the standard for northern realism, and many other great Flemish painters quickly followed him, including Petrus Christus, Rogier van der Weyden, Hugo van der Goes, and Dieric Bouts. These northern lights later inspired Rubens and the 17th-century Dutch masters.

However, Michelangelo didn’t always approve of their work. He said that their paintings only deceive the eye. Instead of portraying higher ideals, like David’s integration of a noble spirit and a perfect body, they show things in their everyday mundaneness. I’ve found some of the young women that they painted rather disturbing. Their pretty long blond hair looks like spun gold, but their faces are so pallid and thin that they look sickly or malnourished.

They probably did look that way at times because famines and plagues recurred, and medical care was often more harmful than helpful. Why did these painters develop this unsparing realism?

The land around Bruges isn’t as picturesque as Italy. It spreads by the sea, around a river that the Rhine flows into. It’s flat and often overcast and chilly.

People struggled to squeeze livings from its sandy soils. Even at weddings, their food was usually humble, as in Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s painting (below). And neighboring countries were often rude. The French ruled the area in the 13th century, and the Spanish took it over in the 16th century. Both taxed its hardworking people and sacked their towns when they rebelled. Why pick on this frugal land?

It was a trading hub between the Rhine, the North Sea, and Paris, and merchants there built international networks. Other states tried to use it as a cash cow, and this encouraged its people to look at the world with a cynical eye.

Nobody had a tougher eye than Reynard the Fox. Flemish people savored stories about his exploits, which were penned by an early 13th century poet named Willem. Historians don’t agree about who he was, but his readers enjoyed the fox’s quick wit. Reynard lived in a world of bullies. The bears and wolves around him were stronger, but he was cleverer. The king had told Tybert the Cat to bring him to his court because he had stolen many chickens. When he reached Reynard’s gate, the fox greeted him, “Good friend! We will go tomorrow. Come and stay with me tonight.”

What would they have for dinner? Tybert said, “I’d sure like a nice fat mouse.”

“Good cousin! You’re in luck! A priest lives near here and his barn is full of mice. I’ve heard him complain that so many dart around that they’ll soon drive him from his house.”

Reynard had stolen a rooster from the priest, and he knew that his son had set a trap for him. He led unsuspecting Tybert into it. The priest heard it snap shut, thought it had nabbed the pesky thief, and joyfully bolted out of his cot naked (many people in the medieval West slept in the nude).

He beat the cat with his distaff so savagely that Tybert had to attack him. He bared his teeth and claws, leaped upwards, and ripped off his penis. His horrified wife shrieked that she’d rather lose a whole year’s offerings for her soul than her nightly pleasure. Nothing was too sacred for Flemish irreverence towards authority.

Some Italians who visited Flanders in the 16th century wrote that its people lacked style. They worked and drank so hard that their lives alternated between stony sobriety and blind drunkenness (Bruegel shows peasants drinking it up on a Sunday as two wealthy visitors appear scandalized).

When I explored medieval towns in Belgium, grey clouds usually covered the sky. Since I always wanted to be sober in order to explore as much as possible, I looked into every one of the many chocolate shops in sight and always carried several pieces with me. I craved something to make me feel warm in the gloomy climate, even around Ghent’s magical late-medieval towers (below).

But Italian artists learned much from Flemish painters in the 15th century. Oil-based painting was first mastered there and then taken to Italy because it allowed artists to give details sheen to make them stand out. The harsher colors of northern painting (cold blues and reds) were also brought south, and they added drama to many Italian works. Piero della Francesca used them to sharply contrast tones in order to emphasize divine ratios. Italian artists also learned northern techniques for making people’s portraits more realistic.

Pan-European trade, Christian traditions, and the ancient Greco-Roman heritage gave both regions many shared meanings, and their ways of looking at the world fused despite the cultural gaps. Flemish cities like Bruges (below) had been wealthy trading hubs since the 12th century.

The great Nuremberg painter, Albrecht Durer, spent two years in Venice, and he wrote that Italy had many of the world’s most pleasant people, and some of its worst scoundrels. The plain-spoken German wasn’t completely at home in a culture that sometimes stressed style over truth. But he brought techniques from its masters north and used them to give medieval visions he had grown up with a scientific realism. Snarling demons look as though they might lunge from the page.

This realism converged from other currents from the Middle Ages as well. The devotio moderna movement grew in the 14th century, and it deemphasized the intellectual focus of the scholastics and emphasized Jesus, particularly his birth, suffering, and death. It also highlighted his mother’s suffering. It took an emotional and devotional rather than contemplative approach to divinity. It was especially strong in Flanders and the Rhineland, but it also had adherents in England (where The Cloud of Unknowing was written), Italy (where Catherine of Sienna wrote of mystical love for God), and Bohemia, where it influenced Jan Hus’s preaching against the Church’s heavy-handedness.

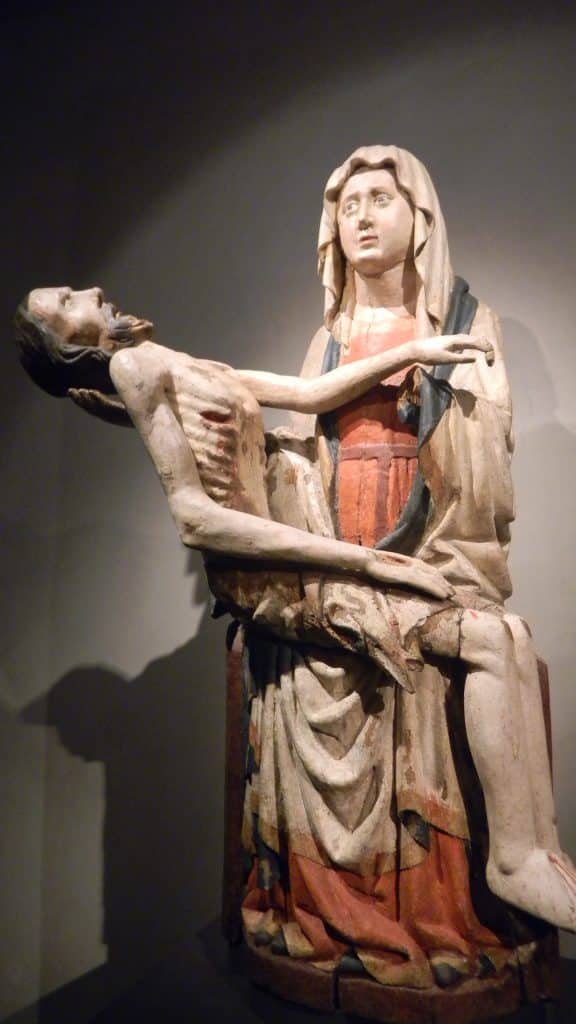

This movement had a huge amount of influence on visual arts. Sculptors and painters now expressed emotional sympathy with the suffering Savior with compelling realism.

Christ as a feeling human being, rather than the universal king, was increasingly worshipped, and artists vividly showed his agony (the above sculpture is in Prague and the crucifix below is in Cologne’s cathedral).

The suffering of the people around Christ was also portrayed. Scenes of his being taken down from the cross became especially popular.

As feelings became emphasized more, the specific was increasingly appreciated rather than the universal. This trend had been developing since the 12th century, when cities were growing, more popular literature was written, and the cult of Mary emerged. Sculpture, painting, and stained glass in the great Gothic cathedrals was becoming increasingly realistic. The builders of those cathedrals and leaders in the new universities tried to cobble all things under one intellectual system, but there was now too much diversity in those dynamic cities to cram into it. Some people looked for alternative meanings.

The magnificent edifices of those cathedrals and scholastic philosophic systems still predominated, but in the 14th century several things converged to make more people question them. The bubonic plague carried away about one third of the souls in Europe.

The papal schism left Europe with two popes vying for top-dog status, and this made some Christians doubt the Church’s authority, since each contestant was excommunicating his rival and his followers. The papal palace in Avignon (below) stood heavy over the town to rival the pope in Rome.

Guests in its banquet hall (below) would have been surrounded by ornate tapestries on the walls. Was he or his opponent legitimate? His palace must have it hard for many visitors to decide.

The failure of the crusades to win the Holy Land left Europeans to battle each other with increasing vehemence. In 1208 Pope Innocent III launched the most ferocious regional crusade, in southern France. Courts in Languedoc, such as Toulouse, were some of the most cultured in Europe. They were highly literate and cosmopolitan, with Jews, Muslims, and troubadour poets. The crusades ravaged them with scorched earth tactics and public burnings of thousands of Cathars. The Church then established an inquisition in Languedoc to sniff out all remaining heretics. Fear and memories of violence now scarred this fecund culture.

The Hundred-Years-War dragged states all over Western Europe into it, and new ways to slaughter people emerged. The long bow was simply a six-foot-tall bow. It was first used in the mid-12th century by the English marcher lords, who were trying to subdue the Welsh, and it became widely used in the 14th. It required a strong arm (a bowman needed to apply 100 pounds of force to pull and release the string), but an experienced bowman could fire a shot every five seconds which could pierce a knight’s armor–a six-fold improvement in firepower, since crossbows required 30 seconds per shot. The English demonstrated this new might at the battle of Crecy, the first major battle of the One-Hundred-Years-War. Their army was marching through France and the proud French knights intended to drive them out. At Crecy the French knights charged, and the English infantrymen launched a hail of volleys with their longbows and routed them. Bodies of French knights fell on top of the bodies of their already fallen comrades. The survivors were shocked to see mere commoners defeat their army.

As the power and prestige of knights were declining, the use of mercenaries increased. These professional soldiers would fight for anyone who gave them enough money or land. They became one of the worst scourges of the 14th century. Their large numbers sometimes inflated local conflicts into a pan-European scale because all the soldiers on the continent would rush to get in the action. Between wars, they created their own action by pillaging towns and villages. The ideal of the gallant knight was being replaced by hoards of ruthless thugs.

Upper-class homes, like Ightam Mote in Kent (above), needed a surrounding wall or moat for protection. The water looks romantic today, but it was a life-or-death investment back then.

Europe had greatly prospered from the 11th century through the 13th, but the world now seemed like a miserable place to many. It was harder to unify it under the balance of Trinity, Church, and king, which Gothic cathedrals expressed so well. It now seemed full of suffering without a benevolent universal agent to protect people.

Folks responded by further emphasizing inner life, intense emotions, and the specific situation rather than the universal order of things. Nominalism emerged in philosophy, which focused on the particular rather than a system of universal categories. Artists represented people’s reactions to specific events rather than serene contemplations, and those events were often traumatic.

This wider selection of situations and emotions to portray gave the developers of three-dimensional perspective more material to put into the new framework. The classical heritage from Italy, no-nonsense northern realism, and experiences from the Middle Ages blended in countless interactions, and three-dimensional perspectives became richer and more compelling. You can read about developments in Italy that also made three-dimensional perspectives immersive. A perspective becomes basic and commonly shared when many cultural currents converge. You can also read about India, China, and Africa.