Many Westerners have assumed that reality is centered on individual objects, distinct domains, linear relationships, proportion, vision, and mimesis (accurate imitation of things while creating artistic images). But equally creative cultures have held other assumptions, including China, India, and Africa. What seems basic seems so because an enormous number of experiences converged and reinforced each other as centers of perspective. The encounters between ancient Greece and Rome strengthened these experience and spread them in much of Europe.

Denis Feeney, in Beyond Greek; The Beginnings of Latin Literature, wrote that any Roman who progressed beyond basic schooling needed to learn some spoken and written Greek. He noted how remarkable it was for an ancient Western culture to incorporate a conquered society’s literature as its own educational standard. The only other time that happened was when the Semitic-speaking Akkadians adopted Sumerian literature, including the stories about Gilgamesh.

In the third century BCE, Livius Andronicus wrote some of the most influential early Latin literature by translating the Odyssey. The Homeric poem’s coasts, voyages, and geography of independent communities resonated with people in Italy and Sicily, who lived in similar natural environments dominated by clearly demarcated coasts, valleys, and plains.

Livius Andronicus converted Greek gods into similar Roman deities. Zeus became Jupiter, Hera was turned into Juno, and Hermes became Mercury. As these translations became conventions, the old Roman deities were given more flesh and color by being associated with the lively stories from Homer and Hesiod.

In the second century BCE, a tragedian named Accius provided a detailed genealogical history of Troy’s royal family, which proceeded from Jupiter to Aeneas’ father, Anchises. He thereby encouraged Romans to adopt Greece’s temporal horizons when they thought about their own origins.

It would have been much harder to convert Indian geographic features (including jungles, deserts, the Himalayas, monsoons, and long rivers) and gods into Roman counterparts. But Livius Andronicus’ Odyssey contained many translations that were based on similar features in the Greek and Roman worlds. Homer invoked Mousa for inspiration at the beginning of his Odyssey, and Livius translated this goddess of song into a Latin counterpart. Denis Feeney noted that his Camena was a water deity which Romans identified with a spring outside their city walls. This choice had several facets. Carmen was a Latin word for song, and the Greek muses were identified with a spring on Mount Helicon in Greece.

Many aspects of Romans’ and Greeks’ experiences were thus similar. Romans added their own gods and modified some events to make the traditional focus on the Odyssey engaging for them. This reinforced Romans’ and Greeks’ emphasis on human-scale events within a short enough timespan to form tangible lineages between current political leaders and the founders of civilization rather than Indians’ projections back to cosmic origins (brahman).

Rome’s treatment of history also reinforced the common Western perspective of foundational events and personages in physically tangible terms and locatable places. In the third century BCE, Naevius wrote the Latin language’s first known historical monograph, which detailed Rome’s war with Carthage in Sicily. It linked Rome’s long-term enemy’s mythical Trojan origins to real events within the audience’s lifetimes, and thus emphasized ideas of history and time that focused on the clash of current societies around the Mediterranean.

In the early second century BCE, Ennius reinforced this perspective by writing an epic in the Homeric poems’ meter (dactylic hexameter) about Rome’s history from the fall of Troy to his own day. Denis Feeney said that Ennius’ work was seen as a universal history, which culminated in Rome’s ascendance as the main event in the world and the universe. He greatly influenced Virgil’s Aeneid.

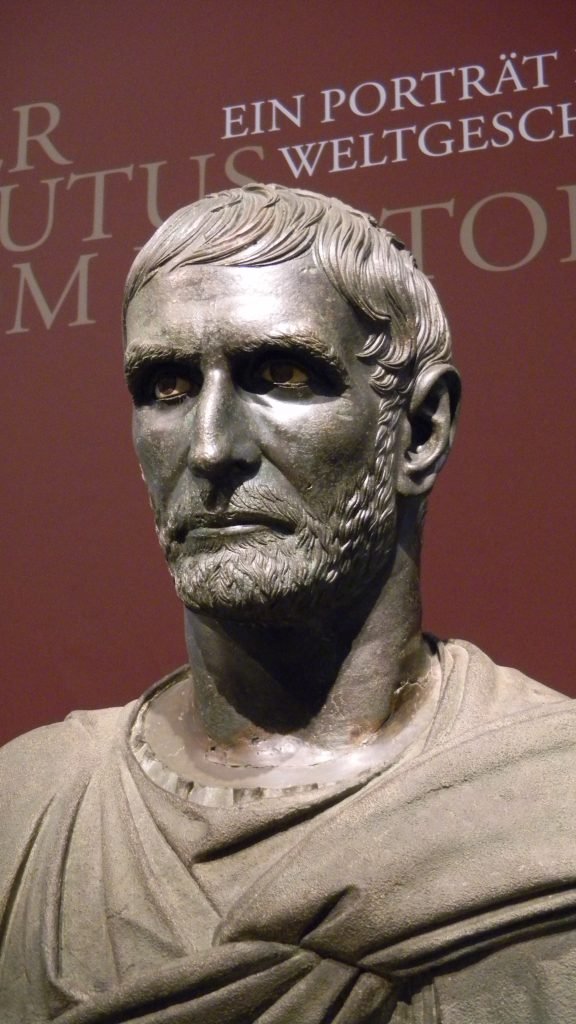

Romans adopted Greek traditions of creating realistic busts of political leaders. Above, Julius Caesar is shown looking physically frail, but iron-willed and emotionally detached as though he operates from a realm that’s above the bustling world. One of his assassins, Marcus Junius Brutus, is pictured below with an equally firm will. Romans created engaging portraits of the most influential historical figures, which made their narratives visually engaging.

In the third century BCE, Fabius Pictor composed a history that derived Rome’s founding date from the Greeks (the first year of the eighth Olympiad, 748–747 BCE). Livy worked on a mammoth 142-book history of Rome from around 30 BCE until his death in 17 CE. He apologized for immediately taking his readers to the ancient past rather than the present, acknowledging that they were more interested in current events. This remote past in his work started with the fall of Troy and Aeneas’ wanderings. Although Rome was the focus in these historians’ books, its temporal horizons were conceived in terms of Greece’s past rather than extended back to much more distant origins.

Roman theater became more inspired by Greece in the third century BCE. The previous Greek influences were less deliberate and systematic, and they were often mixed with popular Etruscan plays, Oscan entertainments, and early Roman improvised farces. But from about 240 BCE on, Romans more directly adapted Greek theater. Their state had become the dominant power in Italy rather than one of several societies, and they were differentiating it from the more “rustic” people. They were showing that it deserved hegemony over all other Italians and claiming that Rome’s culture was on par with their known world’s most prestigious.

Most of the Greek theater that Romans adapted came from its classical age. They translated the three great tragedians from the fifth century (Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides) and comedy writers from the fourth century. The latter (Menander, Diphilus, and Philemon) pioneered the domestically focused comedy that is still the most popular in the West. Menander (below) is still honored at Athens’s Theater of Dionysos.

After the traumas and political upheavals of the Peloponnesian War and subsequent economic hardship after the loss of tribute from the Delian League, Athenians saw Aristophanes’ plays as too free-wheeling. And blatantly insulting political leaders became impermissible after Alexander the Great took over the Greek world and established monarchial rule over it. After the city-states lost their independence, private life often became more satisfying than public affairs, and people’s experiences became more centered on the home. In Athens’s Theater of Dionysos (below), they could view each other as they watched plays that dramatized them.

Comic playwrights then narrowed their focus from state-wide political events to domestic settings, often with a young man and woman in love, the woman’s cranky father trying to thwart the marriage they’re planning, and crafty household slaves and neighbors siding with the youths and duping the old man. Many plays ended in a marriage feast which presaged continued abundance in the succeeding generations. This plot has remained so popular that the Canadian literary scholar Northrop Frye called it “the argument of comedy.” In Menander’s Dyskolos (The Grouchy Man), a misanthropic elder lives with his daughter and their slave. He detests other people and avoids speaking with them whenever possible. A dashing young man meets his daughter and they fall in love, but Dad doesn’t want anything to do with him. The old man then falls down a well, the others save him, he experiences a change of heart, and approves of the marriage. The play ends in a celebration.

Another popular type of comic play begins after a young maiden was raped and she became pregnant. The ravager sees her again without recognizing her, falls in love with her, but does not want to marry her because she is with child. But all is resolved in the end, when they recognize that they were already close enough to lawfully wed.

Comic plays thus often created contrasts between initial threats to and final affirmations of social conventions. The characters often ended up arranging a wedding and celebrating with food, wine, music, dancing, and jokes about sexual bliss that the couple would soon enjoy while producing the next generation. The community’s abundance would thereby continue.

Most comedies since then have retained this focus on domesticity, often with a young romantic couple, a cranky older man, and lively servants or neighbors. Shakespeare adapted Greek new comedy and Roman comedy in his early comedies, and the modern sitcoms I Love Lucy, The Honeymooners, All in the Family, and Everybody Loves Raymond followed many of their patterns. Raymond’s father telling people who disagreed with him to kiss him between the back pockets was a modern Dyskolos.

So as Rome grew and as her citizens were representing human affairs on stage, they adopted Greek traditions that portrayed events in the here and now, and this reinforced the focus on those traditions. The characters they created were people of the world navigating its competitive societies to build prosperous and happy homes. They built theaters throughout the empire which rivaled the ones the Greeks erected.

The one above is in Rome. The photo below shows the interior of the theater in Jerash, Jordan.

Plautus (254–184 BCE) was Rome’s most influential playwright that was born in Italy. He combined Roman topics with traditional Greek themes and settings and used vivid language to bring them to life. Clever slaves were prominent in many of his plays; they were in the know about the misunderstandings between the other characters. Rome’s large and diverse population craved action, trickery, and quick repartee. Plautus’s talents were ideal for pleasing his audiences.

A generation later, Terrance established himself as Rome’s greatest playwright, and he composed comedies with more elevated language and more nuanced characterizations, personal relationships, and judgements. According to the history and classics professor Erich S. Gruen, he used earlier Greek literary standards to set an aristocratic tone and educate the public. So whether refined or ribald, Roman drama was largely inspired by Greece.

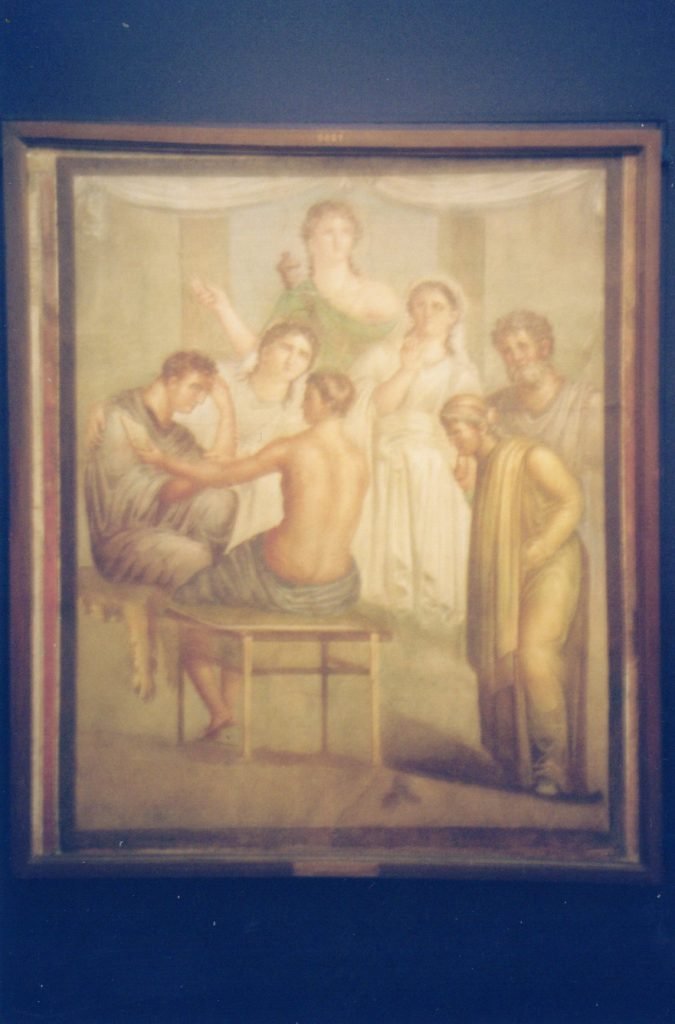

Romans also adopted Greek ways of visualizing the world. Oswald Spengler and Erwin Panofsky wrote that perspectives in both cultures’ paintings focused on the human body. Florentines in the early 15th century developed a mathematical theory of three-dimensional perspective, which is based on the vanishing point in the center and a grid of lines that proceed from the viewer’s frame of reference and converge on it. This has given painters a powerful technique for precisely arranging objects in scenes. But ancient Greeks and Romans centered perspectives on the body, an oval or circle that surrounded a few people, or a herringbone pattern of lines branching from a body’s spine.

These techniques aren’t as pin-point precise, but they make the viewer focus on people’s physical presence. Panofsky, in Perspective as Symbolic Form, wrote that classical antiquity’s art was purely corporeal and that its objects were visible, tangible, and anthropomorphic.

Panofsky also noted that objects weren’t arranged into an abstract spatial unity, like the three-dimensional framework that Florentines defined, but were instead affixed to each other in a cluster. They reflected the old Homeric narratives, which focused on two or a few characters in dialog or combat. Romans thus inherited Greeks’ love of painting scenes that were oriented to bodies in the here and now and to proportioned relationships between them.

Roman sculpture was equally influenced by Greece. As ever more money flowed to the empire, statues were acquired and set up in temples, public buildings, and wealthy people’s homes. Since institutions and elite citizens were eager to project their own prestige, the demand was huge. The industry of creating replicas of Greek sculptures emerged so that artists in Rome were trained in Greek aesthetics. Roman gods adapted from Greek deities shared spaces with statues of emperors and prominent citizens. All together reinforced people’s shared focus on distinct bodies with detailed muscles and facial features.

In the early second century CE, Emperor Hadrian (below) became a classical buff and loved all things Greek.

He built a second agora in Athens (below). Romans constructed several other monuments in Athens, including the Theater of Herodes Atticus, which rises next to the city’s older theater.

Augustus Caesar’s right-hand man, Agrippa, erected a massive odeum in the middle of Athens’s original agora. They constructed a temple for Mars next to it. Since this area had been open for centuries, these buildings changed the agora’s character. The new monuments expressed Rome’s political dominance, but they were all in stately proportioned Greek forms that had graced the city for centuries, thereby reinforcing the traditional aesthetics. The Latin poet Horace thus wrote that Greece took her conquerors captive.

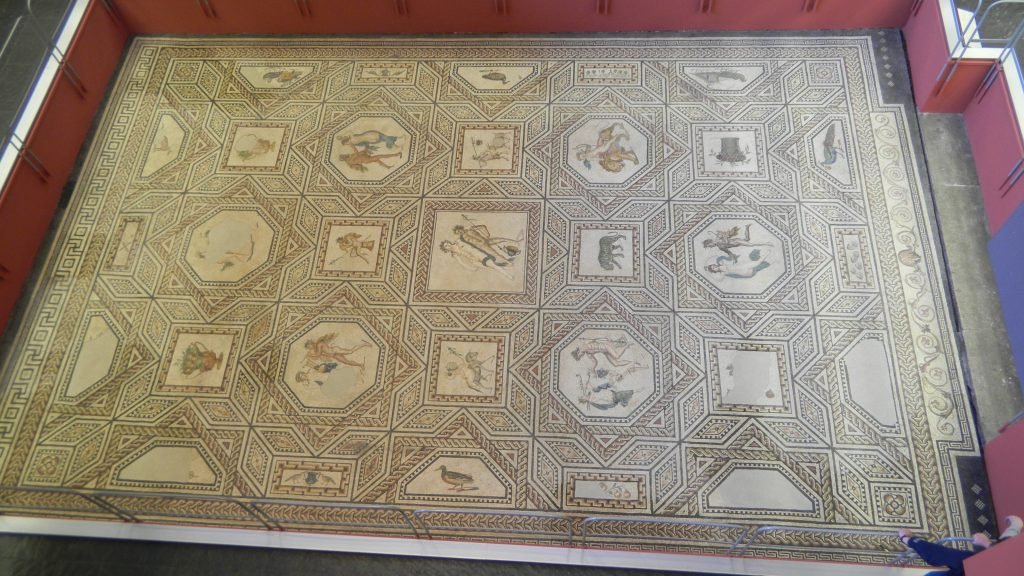

The convergence of both societies took people throughout Europe captive. Rome granted citizenship to newcomers more liberally than Athens did, and as the empire spread through much more of Europe than the Greek city-states, an increasing number of people adopted Greco-Roman ways of thinking and perceiving. These traditions provided shared images of good living and a common mental framework. Cologne became the largest Roman city in northern Germany. When I toured its Roman museum, one of its most prominent items was a mosaic floor of a local who had prospered in this trading hub on the Rhine (pictured above). A large image of a plump peacock within an abstract trapezoidal shape dignified one of the edges.

Being from India, it was a stunningly exotic creature in northern Germany. Peacocks were associated with royalty in Persia and Babylonia, where they guarded harems. As Rome expanded into the Middle East, some of its wealthiest citizens enjoyed these iridescent birds as luxuries. A person displaying its image in Northern Europe would have given locals a message that he was connected with political powers that could acquire all of the world’s wealth and curiosities.

All the other figures in the mosaic (people and more birds) were also portrayed within abstract geometric shapes, including squares, octagons, and shapes similar to trapezoids.

Local guests in this room thus saw an abundance of life forms within an orderly arrangement of static and idealized shapes as a sign of well-being and political influence. Farmers and merchants in the surrounding area arriving to trade would have also seen porticoed houses and public buildings, elegant glass vases, proportioned ceramics, and realistic sculptures of people. In this way, aesthetics from Greece and Rome spread in Europe and became standards of well-being.

They also became standards for beauty and truth. The Nobel Prize-winning physicist Frank Wilczek, in A Beautiful Question; Finding Nature’s Deep Design, marvels at the proportions he sees in particle physics and biology. The physicist Sabine Hossenfelder, in Lost in Math; How Beauty Leads Physics Astray, wrote that ideals of beauty and the beliefs that nature is elegant and simple that they inspire are not scientific but matters of faith. These ideals have captivated people for so many centuries because they were established in many types of experiences more than 2,000 years ago.

Other people developed different ideals about nature, including Southeast Asians, Muslims, and Native Americans.