Most historians think Thais originated in southern China. Tais (Tai is the spelling of the diaspora of ethnic groups who speak the same family of languages; some later settled in what is now Thailand) had lived in Guangxi, Guizhou, Yunnan, and Guangdong. Some might have fanned out around 2,000 years ago, when China’s Han Dynasty expanded from the north. But many historians see the late first millennium CE as the main period when Tais expanded from the borderlands of southern China and northwestern Vietnam (around Dien Bien Phu) and moved into lands that became modern Thailand and Burma. More came into Thailand during the Mongol expansion in the 13th century.

Ancient Tais organized themselves into several little groups and perhaps small states (some chronicles say that these states existed in Yunnan and northern Thailand in the late first millennium CE, before the Khmers dominated much of the area) rather than a single empire with a bureaucracy to unify it, as China’s Han Dynasty did. Tai political systems were more decentralized and personal. Lots of groups formed muang systems. The word Muang was used for the territory that encompassed a cluster of villages.

It also often meant the largest local village, which was the political hub for all the others. But its meaning was personal as well as geographic, because the leader of the most prominent family in the most important village often acted as the entire muang’s headman. Some headmen erected a pillar outside their houses, treating it as the center of supernatural powers, which they probably distributed throughout their territory by conducting rituals. The concept of muang thus included a male with enough prestige to attract followers, as well as local spirit cults, the human community, and the land’s life-generating power (when towns later grew, it also came to mean a fortified town which was the center of power and civilization). Long before the 13th century, Tais were used to residing in intimate groups that were held together with personal relationships instead of a more abstract and centralized Confucian bureaucracy.

The historian David Wyatt wrote that most ancient Tai households were probably single nuclear families. They grew rice and vegetables, fished in nearby rivers, tended domestic animals, hunted in the surrounding forest, made tools, and wove cloth. One to two dozen households cooperated to harvest rice, coordinate water flows, and repair homes and bridges.

People could shift their loyalties to another strongman if he became more powerful or if their current leader became too demanding. Because populations weren’t dense, it was relatively easy to move to another place. Chinese culture was more oriented to a centralized government and settled communities that extended families were rooted in, but Tai ideas that unified the world were more flexible. They reflected a multitude of little communities rather than a huge empire.

Growing rice in small riverine valleys and upland plains, ancient Tais were intimate with nature, and they probably honored spirits of rivers, mountains, rice, trees, the land’s power, and ancestors. They generally lived on a small scale and focused on the immediate landscape and personal relationships. Modern Thais’ preferences for coziness have ancient roots.

Most historians think Tais spread through Thailand, Laos, eastern Burma, and Assam over several centuries in multiple groups rather than one mass migration. The people who moved into Thailand’s central plains encountered the sophisticated Dvaravati civilization.

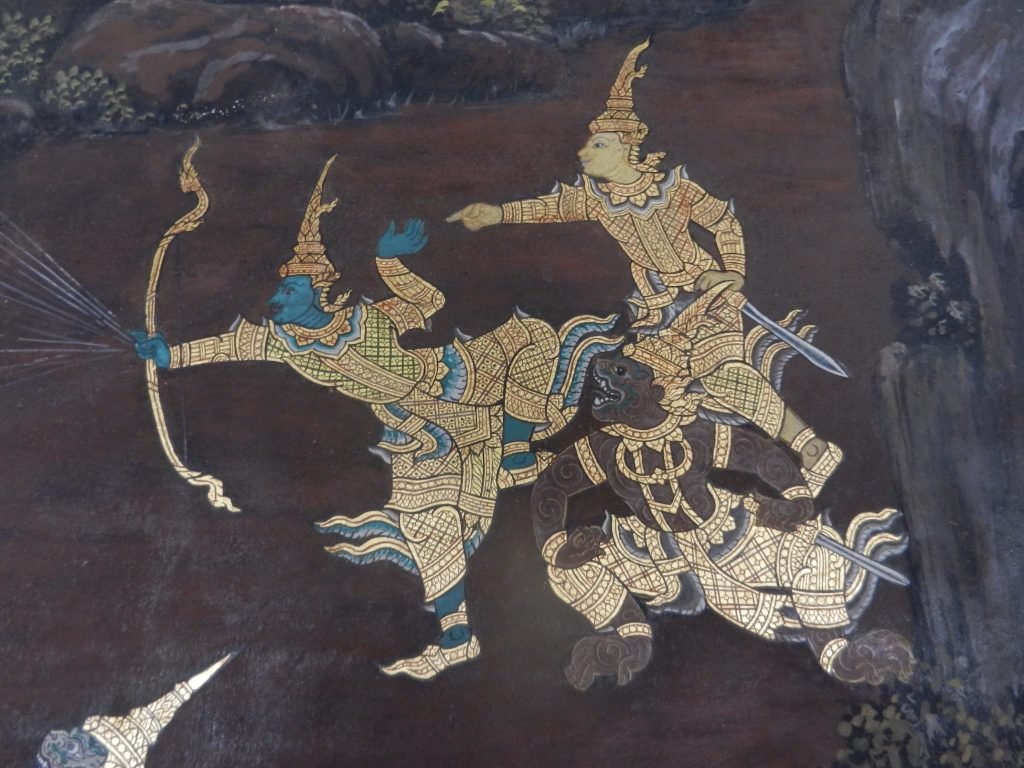

Dvaravati communities had traded with each other for many centuries, and they used money and made refined art that people still admire. Many of their sculptures of Buddhas, saints, and Hindu gods smile, and dancers’ and musicians’ faces (below) curve almost as gracefully as Angkor Wat’s devatas. The art historian Hiram W. Woodward Jr. enjoyed their approachability. Their scale is human rather than monumental, and their faces and forms are usually gentle (though a few statues are of people manhandling prisoners or slaves).

Much of Thailand’s architecture that preceded the formation of Thai states in the 13th century was equally graceful. One of my favorite examples is this stupa form that a Mon kingdom in the north called Haripunchai built in several wats.

The slender outline of this narrow pyramid with five levels makes it more light than bulky, and each side of every level contains three niches with a Buddha statue in a standing position. The five layers of Buddhas thereby calmly bestowed grace on all quarters of the realm. Charles Higham said that most people in Thailand just before 1200 spoke either Mon or Khmer (both are in the same family), so the realm was multicultural as Tais settled in. When the locals were ready to establish independence from the Khmers in the 13th century, enough Tais had moved in to assume the political leadership, but they incorporated Mon art. Sukhothai duplicated this stupa’s form in its own ritual center so that it added yet more lilt to its mixture of shrines.

The Thai states (now spelled Thai because Tai people now had their own states in what is now modern Thailand) thus emerged when many cultures’ art forms were influencing each other and being blended by people who had been used to human-scale environments. Victor Lieberman thought that Tais brought new systems of rice irrigation with them after living in uplands and learning how to create paddies on slopes.

The historians Chris Baker and Pasuk Phongpaichit, in A History of Thailand, noted that Khmer and Dvaravati cultures were more used to constructing large ponds in flatlands to trap rainfall. This tradition culminated in the mammoth reservoirs at Angkor (below).

Both Tais and Mon–Khmers probably shared their farming expertise with each other, and Tais were inspired by the Dvaravati and Khmer art.

Thai culture’s development then became even more enchanting because Sukhothai imbibed art and ideas from several other cultures at the same time.

Sukhothai adopted Theravada practices from Sri Lanka that followed the Buddha’s original teachings about simple living. These traditions avoided the Mahayana speculations that expanded the universe into deities and domains that zoom into outer space and beyond. Thais, accustomed to living in small communities and promoting harmony with local spirits, found Sri Lanka’s down-to-earth Theravada more appealing. Sukhothai’s early kings imported monks and artists from Sri Lanka as they built shrines and monasteries.

Sukkhothai also imported monks and artists from towns down on the peninsula, near the border with modern Malaysia. The peninsula had been an international trading hub for many centuries because water surrounded it on three sides and it was between India and China. The city Nakhon Si Thammarat was the peninsula’s Theravada spiritual center and it had a close relationship with Sri Lanka; Sukhothai’s king brought one of its monks to his capital to become its patriarch.

The peninsula already had an ancient cultural heritage. People had built an empire called Srivijaya in the seventh century (where Malaysia and western Indonesia currently are), and it remained the main power in the region for the next four centuries. It coexisted with Angkor, but both were different in key ways. While the latter was centered on rice farming, the Malay state focused more on the sea.

It straddled the straits of Malacca and controlled trade between India and China, as Malacca would in the 15th century. Chinese thought its forest products had medicinal properties, and they traded silks, lacquers, and ceramics for them. Its main city was near Palembang, in southeastern Sumatra, and it contrasted with Angkor. The historian John N. Miksic wrote that its people probably built their homes over water rather than on dry land, and that the city was several miles long and often only one house wide. A visitor wouldn’t have seen enormous stone temples, but the endless line of stilt homes bustling with families selling goods must have been pulse-quickening too.

The Srivijaya Empire declined in the late 11th century, after a southern Indian state called Chola attacked it to gain more control of Southeast Asian commerce. Several port towns then shared the trade in the straits, and they retained Srivijaya’s artistic influence. The old empire had fashioned many refined statues of Buddhas and Mahayana deities. Some were slender, with bodies in soft S curves, and others were decked with thin garlands of jewelry (Lokeshvara, a bodhisattva associated with compassion is shown below).

These elegant images, which contrasted with the massiveness of many Khmer temples (Pre Rup is below), probably resonated with the people, who lived by the water, sailed in limber boats, and valued the physical and mental deftness that ocean-going trade requires.

They probably inspired some of Sukhothai’s artists.

I found Srivijaya’s environment as appealing as Thailand’s when I visited fishing villages in northeastern Malaysia during my 2007 trip. As in Thailand, dense greenery surrounded intimate communities that emphasized politeness, but their environments were different too. The water in the lagoons reflected crowds of boats and palm trees so that the ripples seemed as animated as the fronds blowing in the breezes. Forests of stilts rose from the waters and supported wooden homes and planked walkways. Most Thais were more oriented to land, but those who migrated to or traded with coastal communities still must have related to the combination of animated energy and cozy villages, and to the flowing art forms (you can learn about Malay culture in another article here).

Burmese connections also grew. Pagan and Sri Lanka had shared Theravada forms of worship since the 11th century. A Mon-speaking society in what is now southeastern Burma also influenced Thai culture. One of its leading monks was brought to Sukhothai because it had become a Theravada stronghold. Both cultures in Burma built stupas and towers in forms that slowly tapered.

Chinese artisans were moving into Sukhothai, and they influenced Thai ceramics. Chinese artists also added design elements to lacquerware and mother-of-pearl inlay, and their zodiacal animals appear on some Thai artworks. Thais assimilated their images and ideas in their own ways, fusing them with the wealth of other cultures’ traditions that they had absorbed.

Of course Indian influences were pervasive, but many came secondhand from lands other than India. Theravada traditions were brought from Sri Lanka, and much of the Hindu art came from the Khmers. The Indian heritage was thus adopted in a looser way than it probably would have been if it all had come directly from one Indian state. By assimilating it indirectly from multiple cultures, Thais could more easily synthesize it with their own sensibilities, adopting what they found appealing and ignoring what they didn’t.

Contact between Sukhothai and the peninsula, Angkor, Sri Lanka, Burma, indigenous Mon people, India, and the Chinese diaspora was continuous. All these cultures added to Thais’ mixtures of ideas, artistic images, and rituals as their own kingdoms emerged. These international connections helped establish Thais’ assumptions about the most fundamental forms and ideas.

Art forms and ways of perceiving and thinking that mix grace and animation became prevalent in Thai culture and have usually remained so, because they converged from an enormous number of places, times, interactions between people, and experiences with the natural environment. People shared ceremonies and pilgrimage sites, traded goods, visited temples, saw graceful shrines and processions of monks, heard the same music, emphasized deference to social superiors, believed in local spirits, and shared the rice growing cycle and the prominence of waterways. All of these converged over time into people’s shared experiences, and this provided them with a common field of meanings that has been uniquely Thai.

The West’s focus on three-dimensional perspective, abstract linear relationships, and distinct objects and their masses also converged from many political centers and an enormous number of influences. Florence, Rome, Venice, and Northern Europe developed these influences together. An untold number of interactions that fleshed them out created the West’s fundamental assumptions about how the world coheres.

So if you ask what made Thailand Thai, or what made the West Western, your horizon opens into an international tapestry with infinite creativity—with limitless abilities to blend multiple societies and to generate new ideas and works of art. Instead of being bound to one idea, art form, or general perspective and treating it as universal truth which holds all things and experiences to its terms, your view can become liberated so that it widens into the diversity of people’s ideas and their interactions with each other and with the environment.

When you combine looking At, With, and Beyond, you can see limitless abundance in the ideas and art forms that your culture has treated as fundamental, and in aspects of your daily life, including your cuisine, interpersonal behavior, and objects that you live closely with. They all glimmer when you see them in enough ways. So do Thai stupas, Indian temples, traditional Native American houses, African sculptures, and Chinese temples. As you keep studying multiple cultural landscapes and comparing them with each other, your perspective can increasingly shift to this radiance. Everything around you, from high art to everyday objects, can become luminous. It can shine, not only in a way that reflects its own cultural milieu, but all societies around the globe.