A previous article here explored Confucianism, but many Daoists have been critical of its orientation to politics. They have emphasized harmony with nature and not trying to impose political institutions or philosophic concepts on it. Just let things be and attune yourself with them. Until recently Laozi was thought to have written the movement’s seminal book (the Daodejing) and to have been an older contemporary of Confucius. But some historians now say that he didn’t write it and that he might not have even existed. The book is actually a collection of short sayings from different sources, which were written around 400 BCE and attributed to him.

The Daodejing begins by saying that the Dao that can be spoken of is not the eternal Dao. With this caveat that words and concepts can’t be imposed on it, we can note that the word’s oldest known meaning was a path on which one could travel or conduct ritualized processions. But it’s not strictly a line from point A to point B, because its meaning was extended to the universe, society, and the norms for mastering a profession or technique. The universe is not most basically a static structure; it’s in flux and we can harmonize ourselves with it and serenely accept the changes it undergoes.

The Dao pervades all existence, and it patterns lifecycles and all other natural processes. Living in harmony with it rather than trying to dominate it is the best way to promote well-being.

The second word in the book’s title is de, which had a long history as a combination of virtue and power that circulates. Confucians adopted the term and associated it with personal virtues, like humanity, propriety, and filial piety. The Daodejing made de cosmic as well and linked it with the Dao, calling it the Dao’s power. It nourishes things and beings and thus gives people the natural ability to align themselves with the universe. Most mess up the alignment by becoming overly concerned with political affairs, material possessions, status, and types of thinking that stuff all things into artificial categories. This fussing makes them deplete their energies as they frantically run around and think too much.

We can limit our knowledge of things by trying to define them too sharply. By presuming to define them, we impose our concepts on them so that we can’t understand them in other ways. Definitions are necessary in academic and other political institutions, but being addicted to them limits our perceptions and knowledge to prefabricated ideas that are abstract and thus distant from what we’re inquiring about.

We can achieve some clarity by using conventional concepts and definitions, but we can appreciate nature more fully by absorbing ourselves in it without weighing ourselves down with intellectual baggage.

We’re naturally aligned with the Dao, and we can cultivate our de by acting more spontaneously and effortlessly. Instead of pre-planning things and getting upset when they don’t go our way or becoming proud and assertive when they do, we can learn to go with the flow.

The term wu wei expresses this alignment, and it has often been translated as actionless action, but it’s much deeper than being inactive. Instead, it’s being so well harmonized with nature’s processes that you can be most effective with the least effort. Another seminal Daoist book, the Zhuangzi, told a story about a butcher who stopped analyzing oxen before cutting them up. He learned to see them holistically with his spirit and slice each one in the perfect place with minimal force. He said that an average butcher had to change his knife every month because he hacked, but he used the same one for 19 years on thousands of animals, and its blade was as fine as it was when it was fresh from the whetstone.

The ancient Greek poet Hesiod, in Works and Days, said that people must labor but he didn’t imagine work as effortless. He told his brother that we have to exert ourselves nearly all the time. People are at odds with nature and must compete with each other in Hesiod’s world. Competition is the order of things, and Greeks honored victorious Olympian athletes and saw Homeric warriors as models of what they wanted to be (the temple of Athena Nike–Athena as a goddess of victory–stands out on the Athenian acropolis–below). But Daoists felt that we don’t need to run ourselves ragged if we appreciate our natural harmony with the universe.

In contrast with Laozi, we know that Zhuangzi lived, and a lot of his fans have considered him one of the most appealing people from ancient times. He told a story about the Lord of the Yellow River flooding during the autumn rains and thereby feeling that he was the greatest being in the world. He then flowed into the North Ocean and realized that he was tiny in comparison. The ocean told him that a frog in a well cannot discuss the ocean because his horizons are limited by the well’s size, and a summer insect can’t discuss ice because it only knows its own season. Likewise, a conceptually rigid scholar cannot explain the Dao.

Zhuangzi’s writings include several other comparisons between enormous and small domains. Like the vast panoramas in several ancient Indian texts, they encourage humility. He used unconventional combinations of ideas to debunk the seriousness and self-importance that some Confucians showed. The man was a disrupter and seemed to revel in it. He taught that words do not fully define the world. Instead, they can trap us in biases that prevent us from appreciating it deeply. Rituals and propriety do not align people with the universe; Confucians emphasize them because they’ve lost their alignment with it. They are uptight about rules, status, and possessions because they’re out of harmony with nature and thus personally insecure.

In contrast with both Confucianism and Legalism, Zhuangzi emphasized the free individual over the state. The rulers are the problem rather than the solution. By imposing laws, rituals, customs, and uses of words, they divide us from both nature and our real selves. A person can best investigate reality by overcoming dependence on these conventions and appreciating the moment without yoking it to pre-established concepts.

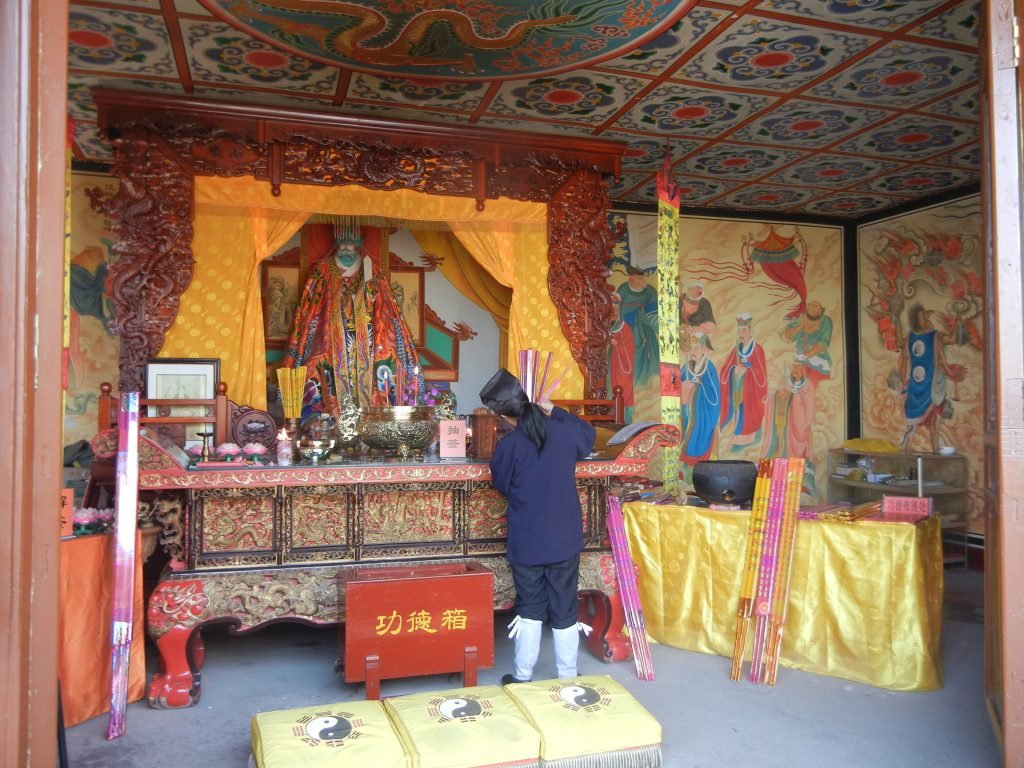

Many Daoists since the beginning of the Common Era have felt that people can attain immortality by cultivating their de. They can achieve it by meditating, ingesting combinations of chemicals, using breathing exercises, controlling sexual energies, and practicing physical exercises that balance the flow of energies in the body. By the early first millennium CE, many Daoists emphasized these quests for eternal life. But in contrast with the spontaneity that the Daodejing and Zhuangzi previously taught, they often focused on complex techniques for meditating and manipulating chemicals to create what was believed to be the elixir of immortality. Some groups built monasteries, priestly hierarchies, and large collections of scriptures. Some adopters of Daoism in the late Han Dynasty were members of millenarian cults which emerged as the dynasty was disintegrating as floods, droughts, epidemics, famines, political corruption, large gaps between the rich and poor, and local warlords plagued it. They saw Laozi as a deity who would save the world and bring about the age of great peace (taiping). If Zhuangzi had lived until then, he might have laughed at people’s tendencies to forget the original simplicity, presume to meticulously manage the basic forces in nature, and project the dao into a messianic figure.

Although early Daoists felt that Confucians are too political, both movements share some basic assumptions about reality. They’re the two widespread religious faiths that originated in China, and they reflect its culture. The eminent sinologist and archaeologist K.C. Chang wrote that neither emphasized a transcendent power which creates and governs nature from a position that’s above it, as Westerners often have. Instead, all processes and beings exist in a holistic universe which is self-sufficient, and their interactions are not determined by anything that’s beyond it. This assumption has many facets and expressions, including yin-yang patterns. Its roots were already ancient when Daoism and Confucianism emerged, going back to the Shang Dynasty and even before, in the Yangshao period. It has been reflected in Chinese assumptions about language, music, painting, and architecture.

This assumption has not emphasized distinctions and opposed forces, as many ancient Greeks did. Harmony of and resonance within a self-sufficient and holistic universe are more basic. Daoists and Confucians have shared this assumption, and it shaped Chinese Buddhism, as we’ll explore in a later article.