It was one of the world’s greatest cities before Bangkok became the capital in 1782. Ayutthaya was founded in 1351, and it became the most powerful Thai state until the Burmese destroyed it in 1767. Ayutthaya could dominate international trade because it was closer to the sea than the other two kingdoms, Sukhothai and Lanna, were. It also had the most flatland for rice farming and could thus support more people. Merchants from all over the known world teemed through its ports in splendid displays of colors that rivaled the vitality of Thai arts. Arabs, Persians, Gujaratis, Tamils, Chinese, Japanese, Malays, Javanese, Bengalis, Portuguese (in the 16th century), and Dutch, English, and French (all three in the 17th century) sold their wares and bought goods there. They loaded their ships with wood, spices, wax, ivory, rhinoceros horns, and hides of deer, buffalo, and cattle. The land’s gifts and merchants from every known state converged in this vigorous city.

Ayutthaya exported rice to another great Southeast Asian state that I later explored on the same trip, Malacca. Its capital hugged the western side of the peninsula’s southern end in what is now modern Malaysia. Malacca lacked extensive lands to farm but it controlled trade through the straits. This was some of the most valuable real estate in the world because it was one of two places where ships could sail between India and China. The other was off the southern end of Sumatra, which was more out of the way. Controlling the straits gave Malacca a lot of wealth to show off.

Like Ayutthaya, Malacca hosted merchants from every known culture, but Muslim sultans ruled this equally colorful melting pot. They governed from a multi-story boat-shaped wooden palace on stilts that perched on a hill overlooking the harbor and warehouses. Malacca sent luxury goods and cotton from India to Ayutthaya in return for rice. These two business meccas grew up together. Both represented Southeast Asia’s new commercial directions after Angkor and Pagan declined, and both added more dazzle to the region.

Angkor also enriched Ayutthaya’s cultural synthesis. Ayutthaya adopted some of its royal rituals after taking many of its eminent priests and artists in 1431–2. In the Indravisaka ceremony, the Thai king assumed the guise of the ancient Vedic god Indra to make rain fall. Royalty and the land’s fertility were thus linked, and Angkor’s hallowed rituals added might to this association. Scribes, accountants, doctors, priests, and astrologers developed a palace language based on Khmer and Sanskrit. So Ayutthaya’s kings projected their own prestige with the Khmer court’s glamour.

Ayutthaya’s cultural effervescence and the land’s allure blended in a spellbinding cityscape. The city thrived at the confluence of the Chao Phraya and Lopburi rivers. Engineers dug a canal to make an island and then built the capital on it. They also constructed canals through the city for transportation. The cobalt lanes carrying long, narrow boats were bracketed by trees and pagodas. Some foreigners noted that streets along the canals were dirty and that high water sometimes flooded them, but Dutch travelers estimated between 300 and 450 shrines in Ayutthaya and noted that almost all were gilded. Architects aimed more for grace than bang. Instead of mountains for Hindu gods, Thais built tall, narrow Buddhist pagodas that curved upwards into needle-sharp points which rose above the tree tops and tickled the clouds. An orchard of spires shimmered above the verdant canopy. Spiritual luminosity and natural abundance intertwined and reached the sky.

The land around the island must have been equally enchanting. A 17th century Dutch merchant named Jeremias Van Vliet noted that the island’s main streets were uninhabited, since it was the kingdom’s political and ritual center. Most people lived in the surrounding area, which bustled with villages, temples, and rice fields. Ayutthaya was thus dominated by waterways, greenery, cozy homes, and tall, lean spires rising over the tree tops.

One of Ayutthaya’s most famous monuments forms a great contrast with Khmer art. The Thai king Prasat Thong erected Wat Chai Watthanaram in 1630 where his mother had lived.

It represents Mt. Meru, as Angkor Wat does, but in a Thai way. A square wall with a tower in each corner and at each midpoint encloses the loftier central spire, which symbolizes the lustrous peak. The surrounding wall, more walls beyond it, and open areas in between represent the rings of land and oceans around Meru. However, the towers are narrow and they gently taper as they rise.

So rather than looking like one huge mass, the wat undulates with steeples that dance as the stupas on the palace grounds did. The wat’s location at the edge of a river that borders the old city amplifies this effect because water reflects the towers. The palace’s builders used pools in the same way.

An excellent way to explore Thai wats is to slowly approach them and amble through their courtyards and viharas. This is how Thais have traditionally visited them. There’s no vantage point from which people can see the whole. This is so in Jayavarman VII’s big foundations in Angkor as well, but they often straitjacket the gaze into long, narrow corridors and small courtyards. Perspectives are usually freer in Thai architecture. They meander through dancing forms and flickering colors. Boat-like halls, curving roofs, and rippling stupas don’t sharply contrast with surrounding spaces. Surfaces and spaces mingle into a happy flow that people can wander through and see from many angles.

Water is often a key aspect of Thai art, and many celebrations include boat processions. The frequent use of water in rituals and daily transportation (at least before the 20th century) has added more lightness, fun, and spontaneity to Thai perspectives. It has also strengthened the relaxed flow of a multitude of forms as a fundamental aspect of reality.

Ayutthaya’s stupa for Queen Suriyothai is a marvelous example of how these lilting forms mix. Thais erected it next to a river to honor her for leading an army against invading Burmese in the late 16th century. It’s narrower and more elongated than the Sri Lankan bell shape, but it also has several indentations in each corner. The scallops and increasing narrowness towards the top make the whole edifice ripple as delicately as the water that reflects it.

I saw how these combinations of water and lightened forms can become magical when I viewed Suriyothai’s monument from the other side of the river. Long, narrow boats glided by. The water, the slender vessels, and the stupa in the background intermixed.

Standing on the grounds of a monastery that was full of traditional architecture, I was looking from one jewel, across the serene water, to another. Since Ayutthaya once glittered with spires, monasteries, the royal palace, and waterways, a perspective of the city would have been less of a survey of an abstract grid and more of a meander from one enchanting place to another.

As I walked around the royal palace’s stupas, some of the smaller spires playfully hid behind the bigger ones and then reappeared. This interplay kept shifting as I strolled. The curving forms danced in a slow and relaxed tempo.

The three main stupas honor kings from the 15th century. People in Ayutthaya deposited relics of royals in shrines because they associated rulers with the Buddha. To them, monarchs protected the dharma on earth. Ayutthaya fought about 70 wars, but kings projected their rule with soft forms in order to appear benevolent.

But the graceful forms masked several tensions beneath the surface:

- Ayutthaya fought about 70 wars during its 416-year life. Its kings competed with other states for Southeast Asia’s increased trade.

- Firearm use began in Southeast Asia in the 15th century. Malacca fell to the Portuguese in 1511, and Ayutthaya entered an arms race with neighboring people, including the Burmese. All scrambled for Portuguese, English, Dutch, French, Chinese, and Persian cannons, guns, mercenaries, and engineers. The blasts made warfare deadlier and contrasted with the ethereal art.

- Ayutthaya’s court often ruled more harshly than the other Thai states. Beginning in the late 15th century, kings partitioned society into levels that highlighted distinctions between upper and lower classes. Much of the beauty that the nobles created was built on the aching backs of the under classes, who had to perform free labor for the king.

- The kingdom was politically unstable. Like Angkor, it lacked rules for royal successions, and many of them were violent. But people were willing to game for the throne because the king profited from the trade. Millions of elephants, rhinos, and deer were slaughtered, and their pelts and horns were sold to foreign merchants. Noblemen were willing to risk their lives for the rewards from this system which siphoned the environment’s wealth.

All the same, the natural beauty, royal glitz, and sleek temples gave locals lots of ways to enjoy the moment and ignore impending political upheavals. As in modern Bangkok, many corrupt and greedy elites masked themselves in a culture that stressed elegance, fun, and smiling complicity. But Ayutthaya was intoxicating during the peaceful times.

The Burmese zealously leveled Ayutthaya in 1767. This orgy of destruction was rare in Southeast Asia, and it traumatized the country so much that it still bears scars. The Burmese destroyed more cities on their way back to Pegu, and large sections of land were depopulated. Hundreds of thousands of people, dazed from wanton pillaging they had never experienced, desperately wandered in search of food. Some Thais still speak of Burma with bitterness. One man that I met called it “the enemy,” and several movie makers and modern writers have portrayed its people as thugs.

But the Burmese spared many stupas. They’re scattered throughout Ayutthaya, which also has modern wats, museums, and the old palace grounds. Most tourists only see a fraction of what is there. The town’s relaxing atmosphere made me glad that I began my first trip to Thailand there instead of Bangkok. The people’s amiability and the remnants of past glory gave me an introduction to traditional Thailand that I’ll always treasure.

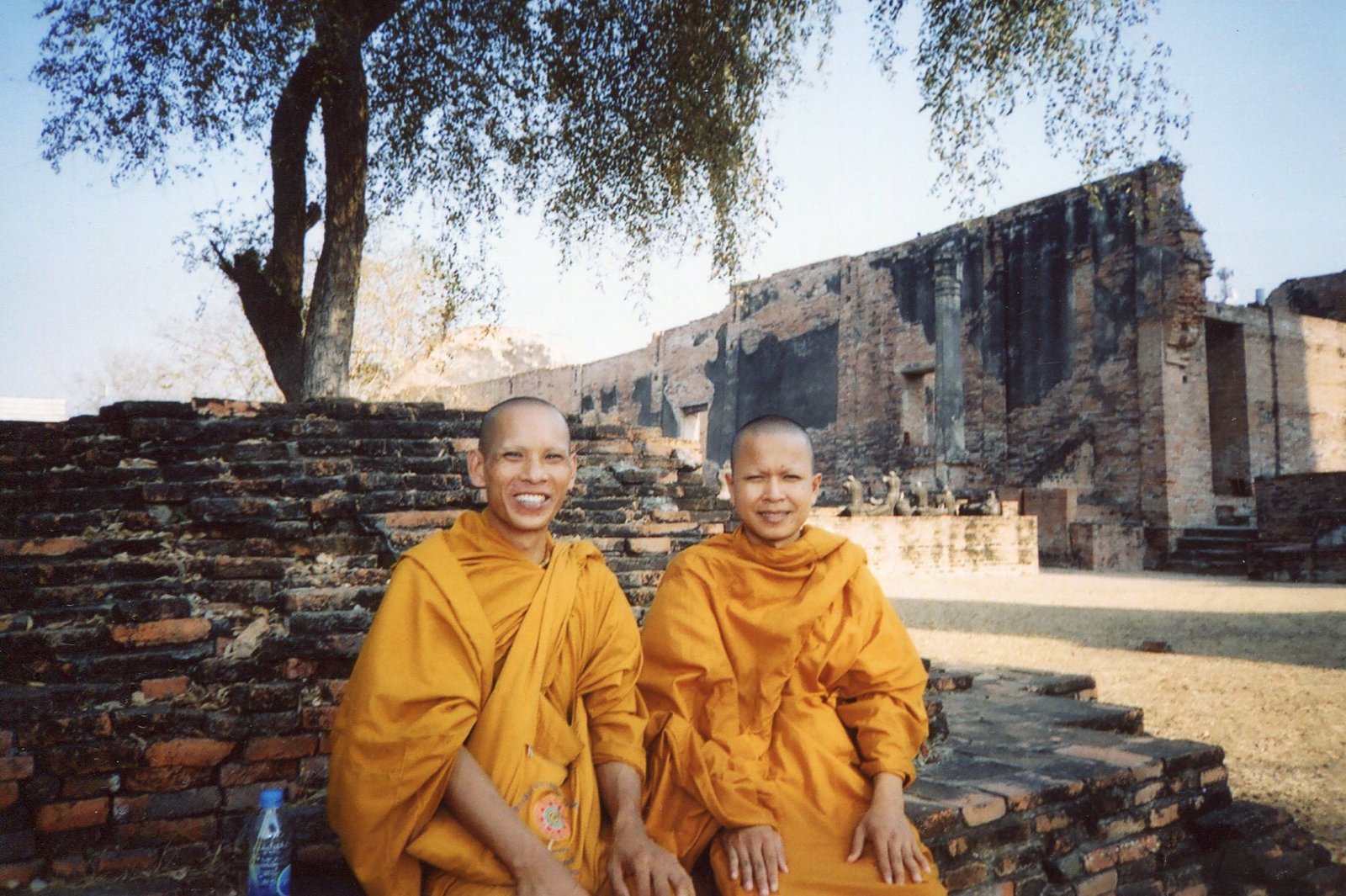

The monk on the left in the top photo took a folder of pictures from his robe’s pouch and showed me his parents and girlfriend. Many Thai men join monasteries for a short time to gain merit for their parents and themselves and then return to worldly life. This man still thought of his secular connections, but he also showed me photos of wats that he had visited all over Thailand. He often smiled while sharing pleasant images of both worlds. Ayutthaya was high on his list of destinations, so it still lusters in people’s imaginations.