After China’s Han dynasty disintegrated in the early third century CE, a succession of warlords became emperor wannabes, but their rules were short lived. Turkic-speaking nomads called Tuoba then established the Northern Wei Dynasty and ruled northern China from 386 CE to 535. They converted to Buddhism and built their capital at Datong (the speculative replica of the palace presides below).

They ruled unforgiving terrain at the edge of Mongolian grasslands.

If the reconstruction of the palace at Datong is reasonably accurate, they combined their land’s sternness with traditional Chinese architectural forms. But they were soon to create a much more inclusive cultural fusion that was as influential as what political rulers and wealthy merchants were doing around the Lower Yangtze. Both areas converged to enable Chinese culture’s continuity from ancient times to the present.

In the fourth century CE, the philosophers Dao An and Hui Yuan more deeply and widely established Buddhism in China, and they made devotion to artistic images central. Northern Wei kings blended this practice with expressions of their own authority.

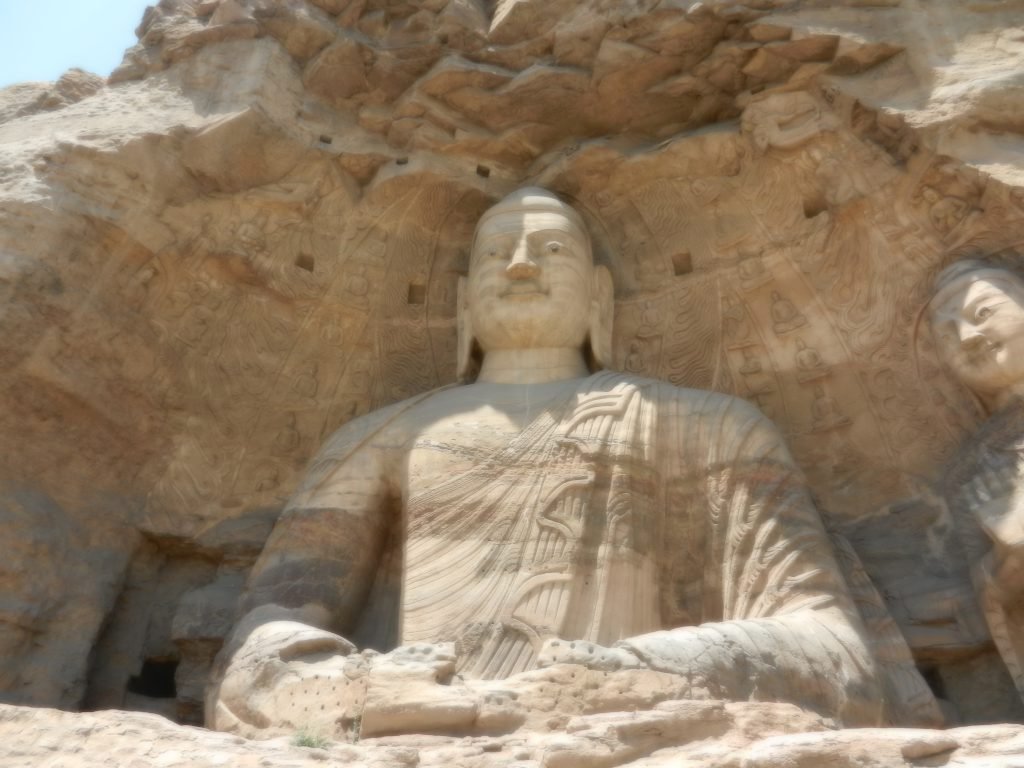

The earliest Yungang caves followed a militaristic aesthetic, with enormous Buddhas in simplified shapes that can make a person fear that he’ll be crushed if he sneezes in front of them. The historian Mark Edward Lewis, in China between Empires, wrote that the first five caves built at Yungang might have portrayed Wei emperors as Buddhas. Monks in the southern dynasties gained the privilege of not having to bow to the emperor, but the Wei Dynasty’s chief monk declared that all monks should bow to the king, asserting that the ruler is an incarnation of the Buddha. He worked in the government department that oversaw Buddhist practices, appointing officers for the realm’s major religious establishments. Some Chinese scholars have called the initial five caves (16, 17, 18, 19, and 20) the Five Imperial Caves (the Buddha in Cave 18 is shown below).

Northern Wei emperors deported thousands of laborers and craftsmen from the northwest when they conquered it in 439 and forced them to build their capital and its surroundings. Influences from northwest, including the caves at Dunhuang, have been seen in the Yungang caves (below).

The art historian Angela Falco Howard, in Chinese Sculpture (in the Yale University series on Chinese art), wrote that Tuoba rulers believed that their ancestors would emerge from a sacred cave, where their descendants were honoring them. Tuoba culture then relied on Chinese institutions and aesthetics as it settled into agricultural life, and it blended them with its own traditions.

Its kings soon portrayed the Buddha with a longer body than the sturdy early statues. The newer figures are dressed more like Chinese noblemen than Indian aesthetics. Other people are shown with the same courtly elegance (below).

Music has been deeply appreciated in China since antiquity. These celestial musicians look like transplants from a well-fed royal court.

The Wei Dynasty also brought artists and craftsmen from the northeast. People from east to west blended their traditions into pan-Chinese art.

They converged to create the continuity and breadth of Chinese culture.

The lush carvings and painting from Cave 10 combine influences from many regions.

In 494 Emperor Xiaowen transferred the capital south to Luoyang. Blends of artistic styles from Datong inspired artists during the great Tang Dynasty, including the makers of the Longmen grottoes (below).

Buddhists in Datong continued to erect temples with Chinese architecture. Huayan Temple (above) was built by the Khitan in the twelfth century, when the first great Gothic cathedrals and Angkor Wat were constructed.

The Shanghua Temple (above and below) was also built in the twelfth century.

Datong is now a modern industrial town with about 3 million residents.

Parents were picking their kids up from school in the above shot. Most of the youngsters are probably immersed in social media.

But they’re still absorbing Datong’s proud heritage.