Ancient Greeks’ minds had many deep roots, including the body. Their especially intense love of athletic games helped encourage them to assume that reality is a human-scale field of distinct entities which can be clearly seen. This assumption still characterizes much Western thought, so we’ll explore its athletic roots here. Fortunately, we won’t need to enter any boxing matches.

Olympia’s local aristocrats had consulted its oracle of Zeus and organized athletic contests since at least the eighth century BCE, and competitors soon came from more distant lands. By the early sixth century BCE, three new international sporting festivals were established. The Pythian Games began at Delphi (pictured below), the Nemean Games started in an area between Corinth and Argos, and the Isthmian Games were established near Corinth.

Sporting matches were now pan-Greek. Athletes first competed with their peers for personal and tribal glory, but by the sixth century, they represented their home towns. The whole city now rooted for its heroes. Since the Greek world was a patchwork of independent city-states, these festivals became one of the main ways in which its people shared experiences and developed a common identity.

The playing field, the civic agora, and the amphitheater had common traits that reinforced Greeks’ ideas about the world. All were open areas in which people were within clear sight of each other. Instead of the vast subcontinent Indians lived on, the most meaningful places for Greeks were human-scale and out in the open. They allowed folks to scan the whole venue, and all those eyeballs could see the same things. Nothing was mysterious or visible only to priests in trances. The world seemed fathomable and rational.

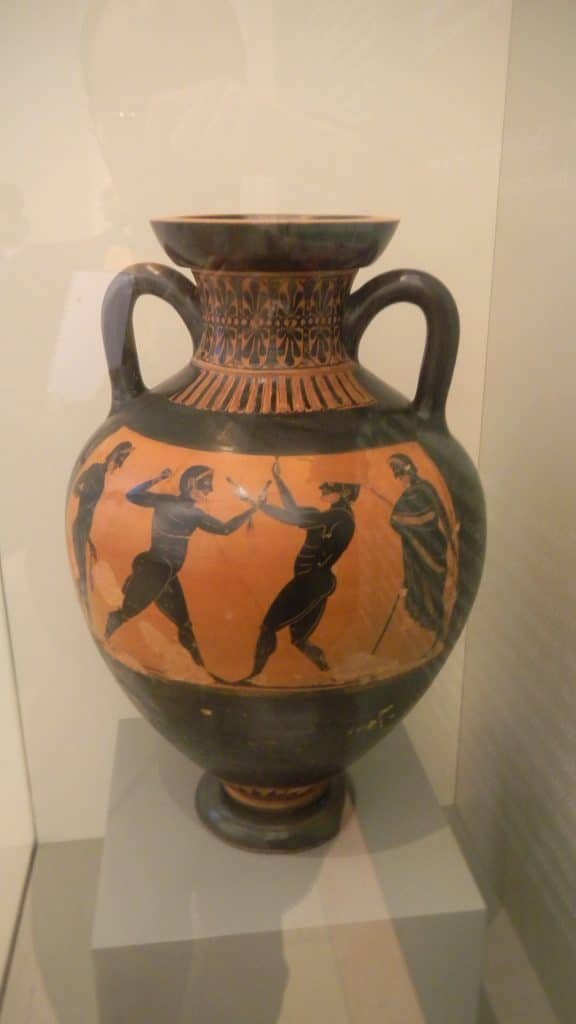

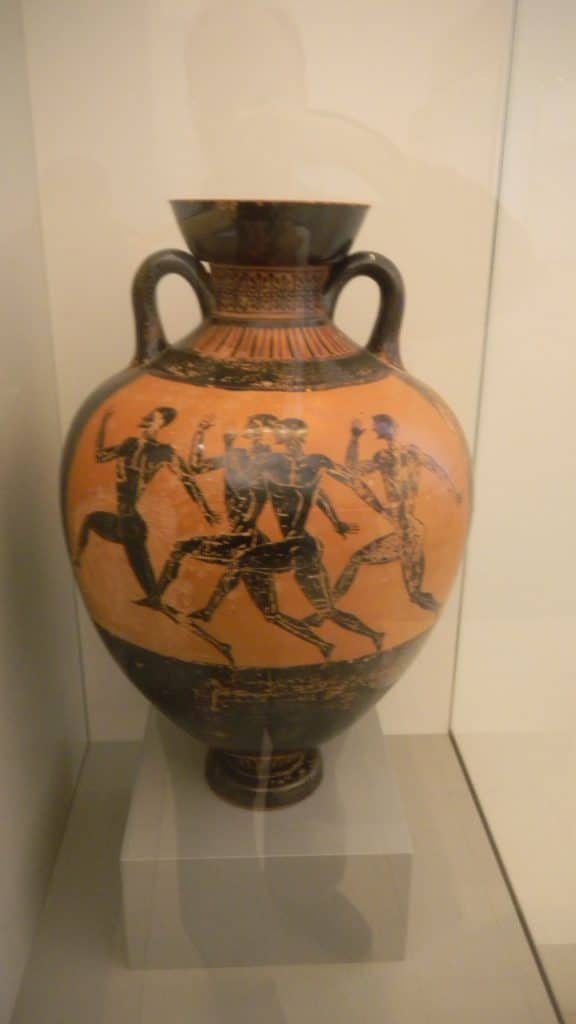

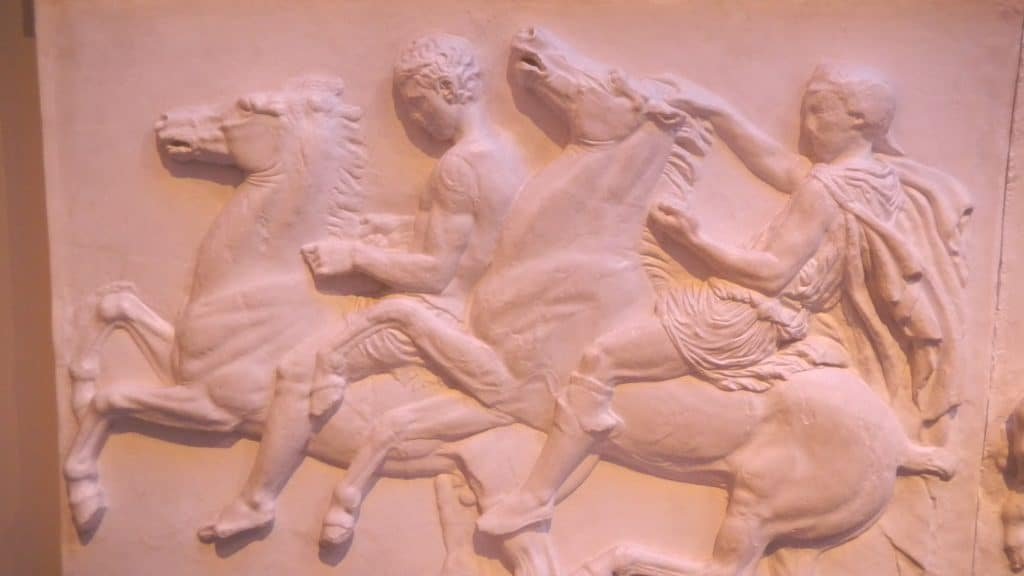

What spectators at the games saw was agon (contest/confrontation) between two people (wrestlers, boxers, or charioteers) or a few (foot racers, long jumpers, javelin throwers, or discus throwers). They watched distinct entities interacting with each other. Relationships between visible objects were the main focus rather than Vedic priests’ enormous cosmic field and the sonic vibrations emanating through it.

The Iliad gave Greeks a vivid model for viewing athletic competitions. Achilles’ best friend, Patroklos, was slain in the Trojan War, and the grieving warrior staged funeral games to honor him after his body was burned on a pyre. The poem gave riveting descriptions of the matches, which are so engaging that every modern sportswriter would do well to read them.

Odysseus and Ajax squared off for a wrestling contest. They wrapped their thick, brawny arms around each other, and so tight was their embrace that their limbs looked like a building’s rafters fastened against each other. Neither could immediately throw the other. Their bones crackled, their flesh reddened, welts rose and blood flowed on their ribs and shoulders, and sweat poured down their trunks. Ajax finally hoisted him, but the always clever Odysseus kicked him in the back of a knee and threw himself onto his chest as his mighty opponent fell. Both kept grappling and clawing until Achilles stopped the contest, declaring it a draw. He didn’t want two of the best Greek warriors injuring each other in a sporting match.

Both heroes then raced each other, and Ajax immediately bolted ahead. But Odysseus knew that gods help people who honor them. He prayed to his patron, Athena, to spur him on. Since she was the goddess of cleverness, he was her kind of guy. She infused strength into his legs and made Ajax slip on a sleek pile of cow dung. He fell face-first so that excrement filled his mouth as Odysseus streaked past him. Ajax spat out the dung and bellowed that Athena helped her favorite like a mommy coddling her boy. The Greeks loved lingering over details of interactions between two people. They had sharp eyes for turns of events and were masters at dramatizing them.

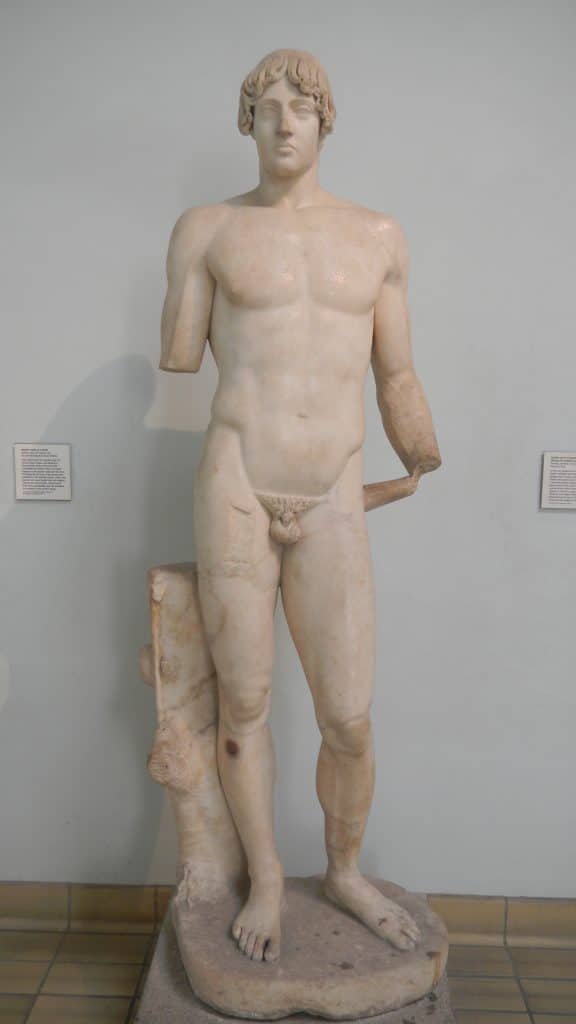

Spectators at real sporting matches saw the body in full glory. Athletes competed in their birthday suits, displaying the male physique at its physical peak. Greek sculpture developed at the same time that the games did, and larger-than-life-sized statues were made of young men in the nude, facing the front in full grandeur. People saw the male nude as the height of beauty. It represented the perfect distinct entity by being strong, independent, and in control of itself (sculptors began to fashion life-sized female nudes in the fourth century BCE).

Kenneth Clark, in The Nude; A Study in Ideal Form, wrote that the games gave the Greeks’ cult of physical perfection religious dignity. The male body’s strength and proportionate form reinforced their model of reality. Statues first faced the front and looked straight ahead, and their limbs hung in symmetry with each other. Clark likened early Greeks’ statues to their temples, with two column-like legs supporting a flat torso which is crowned by a broad chest.

By the sixth century BCE, the men with those splendid distinct bodies represented separate places. Athletes competed for their city-states’ prestige, and this reinforced Greeks’ views of the world as a collection of distinct locations contesting with each other. Sculptors fashioned statues of proud victors in the nude, poets compared Olympic champions to gods and Homeric heroes in strength and beauty, and cities built gymnasia where youths trained for athletic competitions and military battles. All this cultural activity reinforced the focus on distinct entities and locations.

By the end of the sixth century BCE, sculptors made the transitions between statues’ sections smoother so that the body was one graceful whole rather than a collection of geometric shapes. They also showed muscles, veins, hair, and facial features more realistically so that the statues were the most life-like sculptures that any culture had created by that time according to Western aesthetics.

Those figures were different from the ancient Khmer sculptures of Hindu gods, Buddhas, kings, and warriors (one at Preah Ko is shown below).

Clark wrote that those Greek and Asian sculptures represent a universal idea, which associates the strong masculine body with spiritual perfection, but a key difference emerged in Greece. The Asian statues are less defined. Their bodies are thick, solid, and proportioned, but their muscles and bones are not as detailed and they sometimes don’t show at all (the revered Phra Singh Buddha statue in Chiang Mai is pictured below).

The Eastern sculptors were looking at the body and thinking more of a spiritual or political ideal which it represented. But Greeks were looking at the body and seeing flesh, muscles, sinews, and veins. They savored the details of surfaces and the distinctions between areas. Washboard abs and rippling biceps provided contrasts on the surfaces. Details of the body didn’t need to serve spiritual or political ideals; they were valid on their own.

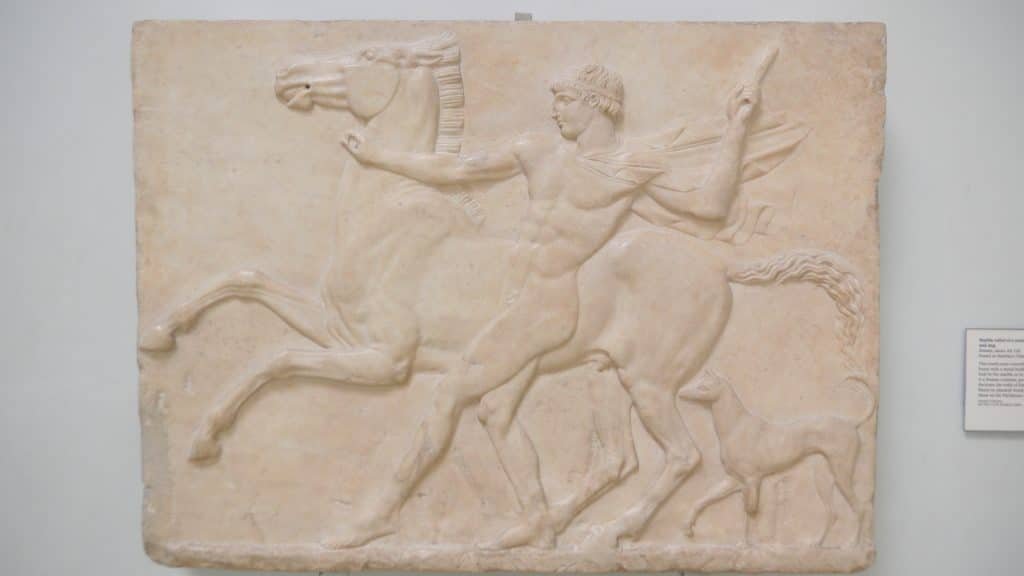

Ancient Greeks developed sharp eyes for turns of events as well as physical details. A book by Marcel Detienne and Jean-Pierre Vernant called Cunning Intelligence in Greek Culture and Society examines some key terms for this kind of focus.

Phronesis and metis were words for a kind of knowledge that the Greeks highly valued. Phronesis meant foresight and prudence–the ability to anticipate a situation before it occurs. Phronesis was not just intuition or a good eye; it was deliberation aimed at a desired result. Metis had a similar meaning. A person of metis is always ready to pounce and take advantage of a situation when the opportune moment arises.

A related concept was kairos, which meant opportunity. Metis seizes the opportunity, even if it’s fleeting. R. B. Onians, in The Origins of European Thought, wrote that the earliest known uses of kairos, which are in Homer, referred to parts of the body that a weapon can most easily penetrate. The word was later generalized to mean target and opportunity. According to Onians, it also meant due measure, because an opportunity or target is limited. Taking advantage of it or penetrating it requires a precise aim.

Homer expressed another aspect of metis. He called Odysseus polymetis–an expert at all sorts of tricks. He had many talents for getting out of trouble; he could assume many disguises and find his way out of any kind of problem. These talents were necessary because he faced a lot of opponents who threatened to overwhelm him. The giant Cyclops tried to crush him with brute force. The dozens of men who were trying to steal his wife and home tried to overwhelm him with their numbers. Circe and Calypso tried to seduce him with their charms. Poseidon had the vastness and power of the ocean to torment him. Odysseus’s metis was contrasted with overwhelming forces that can obliterate a distinct hero. He needed the ability to outfox the characters around him, and Greeks admired him for his ability to do so.

Constant competitions made Greeks focus even more on details of interactions between people and dramatic turns of events. Contests were a common part of many Greek religious rituals. Athletic games, competitions between choirs and reciters of heroic poetry, and contests between playwrights and actors were frequent in the annual cycle of rituals. Since Greeks envisioned Olympian gods in conflict with each other, they imagined them as watching and enjoying human rivalries. The matches intensified people’s focus on each other and the importance of honor in the community.

Athletic games and other contests helped create ancient Greeks’ focus on agon–on competition between opposed entities. These contests were out in the open so that all community members could see the participants interacting with each other in a field which was visibly clear and within the human scale. Other experiences converged with athletics to create this orientation, including theater, law, agriculture, and Homeric poetry. Ancient Indians developed more concepts of subtle energies flowing through a vast field, and ancient Chinese focused on cyclic flows, Confucian virtues, and the central importance of the royal court. Each culture’s thought converges from many types of experiences which resonate with each other. We now have the kairos to explore many cultures and synthesize new ways of thinking.