Swahilis have an ancient heritage of blending East African Bantu cultures with Arabic and Persian influences. Their fascinating society has about two million members. It’s little known outside its region, so we’ll explore it here.

Prosperous trading communities had already existed on Africa’s east coast long before Persians and Arabs arrived. In the first century CE, the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, which a Greek-speaking writer living in Egypt wrote, described settlements south of the Horn. The main trading port was called Rhapta, which most modern historians have located in Tanzania, though it might have shifted between places. In the sixth century CE, several settlements from Mogadishu (up in modern Somalia) down to the Comoros Islands and the northern tip of Madagascar expanded. Most were already culturally diverse, combining iron-using groups that both farmed and fished, pastoralists focused on cattle, and hunter-gatherers (some people probably mixed several of these ways of sustenance). They now increasingly used boats to travel up and down Africa’s eastern shore and islands. Communities developed traditions of absorbing people from many other places.

When Islam emerged merchants from the Arabian Peninsula and the Persian Gulf sailed south and added their cultural wealth to the Indian Ocean. They brought pottery, fabrics, dates, onions, wheat, barley, lentils, raisins, salt, and iron tools to East Africa. In return they purchased ivory, gold, perfume, wood, rice, sorghum, cattle, meat, coconut oil, shells, dyes, and slaves. They traveled down Africa’s east coast in limber vessels with a tall triangular sail which enabled them to move against headwinds. These people partnered with leaders of coastal settlements, and Swahili culture coalesced when African and Middle Eastern traditions blended. By the mid-eighth century, Muslim traders became prominent in some of East Africa’s already culturally rich settlements, when a timber mosque was built in an early Swahili town called Shanga.

The Swahili cities later impressed medieval Middle Eastern and European travelers. In the 11th century, Persians and Arabs came to Mogadishu during the annual trading seasons and met merchants who carried gold from southern Africa. By the 14th century, the fabled city Kilwa became a more important center of East African trade. On an island off Tanzania’s coast, it was able to establish a gold monopoly by being closer to gold fields in southern Africa. Marco Polo found it impressive, and Ibn Battuta thought it was one of the most beautiful cities in the world.

Leading Swahili commercial families built large terraced houses from coral limestone. Many homes adjoined into complexes with several courtyards; the historian Peter Garlake figured that upper-class families clustered together and ran businesses as partnerships. Ibn Battuta wrote that when a ship docked at Mogadishu, little boats carrying young men approached it. Each held a covered dish with food, presented it to a merchant on the ship, and announced, “This man is my guest.” Every trader on the ship was then taken to his host’s house and accommodated there. The host then sold the merchant’s goods in the community and made purchases for him.

The size and elegance of Swahili leaders’ homes facilitated the commercial exchanges by showing that the hosts were worthy business partners. Wooden door frames carved in intricate floral patterns often separated public courtyards from interiors, rooms were lined in a sequence that became increasingly private, and inner rooms had several levels of rows of little wall niches for displaying luxurious items.

Hosts and merchants shared feasts in which they negotiated business deals. Banquets were also common occasions for local governments to solidify their bonds with the community, since many of the largest Swahili towns in the Middle Ages were independent states with their own sultans. These commercial and political feasts seem to have been ritualized, with opulent tableware that included ceramics from the Middle East, Africa, and China to show the hosts’ importance. By the 15th century, white lime plaster covered homes’ exteriors, reflecting the sunlight and making them seem luminous. The coral houses, prestigious goods, and ceremonial exchanges instituted high standards of elegance that were expected of Swahili leaders.

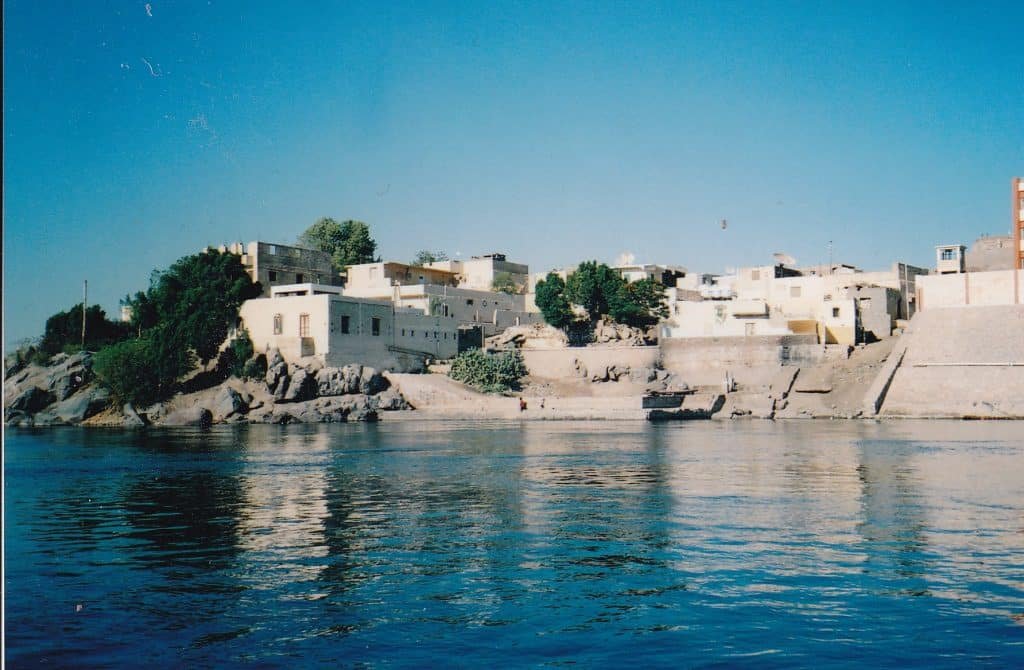

The 14th-century king al Hasan ibn Suleiman increased Kilwa’s splendor by building an enormous palace by the water. He constructed it out of coral and covered it with lime plaster that gave it a smooth white finish. It enclosed several courtyards and a pool. The town’s Great Mosque was erected in the tenth or eleventh century, and worshipers added 30 square arched bays to the prayer hall by the fifteenth. Mixing with the sparkling ocean and cooling sea breezes, the white coral buildings must have seemed divinely pure.

The Portuguese destroyed Kilwa in the 16th century, took over its trading network, and moved their base south to Mozambique Island. But Swahilis regained some of the western Indian Ocean trade in the 18th century. Their civilization has now spread far beyond its homeland.

A Swahili man that I met was proud of his culture’s distinctness and considered West Africans different from upstanding Swahilis and other East Africans. “West Africans are flashy.” Some of their exuberant projections of ase (a Yoruba word that means the ability to make things happen) struck him as loud. Marc J. Swartz, in The Way the World Is; Cultural Processes and Social Relations among the Mombasa Swahili, detailed a complex of Swahili words that have encouraged a focus on restrained and elegant behavior, including uungwana (nobility), utu (civilized behavior), and fakhri (honored standing in the community).

I showed Mohammed a book about Thailand that I had just bought and was curious about his reactions to a very different culture than his. It’s called Very Thai, by Philip Cornwel-Smith, and it’s packed with photos of Thailand’s modern pop culture. Amulets, uniforms, company logos, cartoon mascots, pink napkins, bright paintings on trucks and buses, potted gardens, shrines on taxis’ dashboards, and soap opera squabbles bring the traditional Thai love of flickering colors and irreducible variety (which I immensely enjoyed on the way to Mauritius and detailed in Thinking in a New Light)to the contemporary world. I still thumb through it and laugh out loud every time. But Mohammed only commented on the lady-boys (men in drag) even though they only occupy a few pages. I pointed out other pictures, with their wealth of colors, vibrant mixtures of forms, and the people’s love of fun. “Only a small percentage of Thais are lady-boys.” But he still didn’t connect with the effervescent images. He enjoyed a book that I showed him about Egyptian art during Mamluk rule (1250–1517), which had pictures of Cairo’s many mosques, tombs, and madrassas from that time. He savored it so much that I bought him a copy the next time I passed the store.

Swahili culture is even richer than what many Swahilis have realized. Communities on East Africa’s coast exchanged goods before Arabs and Persians came. African farmers, fishermen, animal herders, and hunters settled where the later commercial towns grew, and they formed societies that sailed and traded. Swahili is closely related to Bantu languages in Kenya and Tanzania. It later acquired many Arabic loan words. As more Arabs and Persians came, settlements grew into larger towns with firmer class distinctions. Middle Eastern merchants formed an elite stratum, but their coral houses were surrounded by Bantu farming and fishing communities with their own ancient traditions.

Bantus have traditionally believed in spirits and witchcraft, and have used magic for healthy crops and large fish catches. Most didn’t attend Quranic schools and couldn’t afford to seclude their women. Many females labored in the fields with the men. Elite families distinguished themselves from farmers, maintaining oral poetic traditions that traced their descents from the first settlers, who were supposed to have either come from Middle Eastern cities (often Shiraz, in Persia) or a society below Africa’s horn called Shungwaya, which hasn’t been definitively located. Men in the leading Swahili families were civilized town dwellers, credit worthy, dressed in long white gowns, adept at poetry, and housed in lofty coral buildings. But Islamic and African traditions fused more than the top Swahili families admitted. Few people lived exclusively in one world, because local farmers and fisherman made up most of the population. The coral homes were surrounded by large areas of wattle-and-daub dwellings with thatched roofs. And not all Swahilis have lived in prosperous towns; many have resided in rural communities between them. James de Vere Allen, in Swahili Origins, wrote that only a minority of Swahilis lived exclusively by trading. The commanding coral houses made up only a small part of people’s visual environment.

Although Islam frowns on some Bantu traditions of venerating spirits, elites also honored them at times. Swahilis sometimes ignored distinctions between benign Islamic spirits associated with towns (jinn) and Bantu spirits from the country (which inhabit rocks, trees, the sea, and other natural features) when plagues or droughts came. Both groups also practiced magic to promote well-being. Women have often been the leaders in spirit possession cults and dance societies. Communities along Africa’s eastern coast celebrated the end of Ramadhan with carnivals, and people danced long into the night. Like other folks in sub-Saharan Africa, Swahilis commonly honor ancestors. Many hold annual Koranic recitations at their graves, feeling that their predecessors can reward or punish them according to the amount of respect they’re given.

With its ancient heritage of trading, East Africa’s coasts and islands have fascinating cultural blends. I found more in Mauritius. The area around the western Indian ocean has much more cultural wealth than most people realize. You can also explore even more at Petra, which was a major trading hub for the area.