Many historic temples grace the northern Thai town of Nan, so I spent several days there. Wat Ming Muang was low on my list because Michael Freeman, in “A Guide to Northern Thailand and the Ancient Kingdom of Lanna” wrote that it’s “in stunningly bad taste.” But taste and judgements about what’s beautiful are greatly influenced by culture. Thai thought patterns are unique, and often difficult for outsiders to understand. A closer look at Wat Ming Muang will give us a perspective on a fascinating world.

I do agree that the above guardian is ugly, but it’s supposed to be. It keeps souls with bad intentions out.

Many good spirits successfully entered to pay respects to the temple’s city pillar in the form of Shiva linga. This is a phallic symbol adapted from India about 2,000 years ago, which embodies the land’s power to generate life. Thais blended it with their own ancient tradition of erecting a pillar in front of the local headman’s house to function as the axis of the area’s energies. Towns today still have this pillar, which is called lak muang. Bangkok also has one, which is catty-cornered from the Grand Palace. So Wat Ming Muang does lots of business, since many locals see it as a source of well-being.

From a distance the pavilion that houses the linga can seem as tasteless as a faux diamond suit. But look closely and a beautiful world opens up.

I began to enjoy the colors: The white that dominates the temple, like the golds and silvers in many other Thai shrines, evokes a luminous spiritual world. Under the tropical sun, these hues seem to radiate energy, and their cheeriness can make it benevolent.

The baby blue background softens the white.

The roof’s crown’s tapering form and the building’s color scheme make it seem to dissolve into the sky. At the top, the Buddha smiles into the four cosmic directions. His compassion reigns in the center of it all. When you look inside–

Each of the four side’s upper area is covered with designs in the same colors. They blend a lot of cultures’ ideas. At the bottom, you can see Chinese Zodiacal animals. The bull in the center is Shiva’s traditional mount. A graceful Thai stupa rides on its back. And lush vegetal patterns embrace this multicultural blend.

But everything blends in a way that transcends categories:

1. The abundant vegetation in the tropics

2. Colors that are both luminous and soft

3. A building’s form that seems to radiate energy on earth and dissolve into the heavens

Things aren’t sharply distinguished or defined. All tolerantly mesh in an endless variety of ways. One beautiful perspective after another can open up. All life forms can thrive with the Buddha’s compassion.

But we haven’t looked at the main part of Wat Ming Muang yet. Freeman said that the vihara (public assembly hall) is especially tasteless.

But look closely enough to enter Thai ways of thinking, and your definition of beauty might become more inclusive.

I do feel that it’s overdone in places.

You wouldn’t find these front columns in Athens, or even Vegas.

The three-headed naga guarding the entrance seems to say, “I’m uglier than you are.” But when I got past the first layer’s kitsch and examined the vihara more closely, I found the building incredibly beautiful.

Little plaques with scenes from people’s lives line the building. Above, we see a procession of folks honoring an elegant Thai stupa.

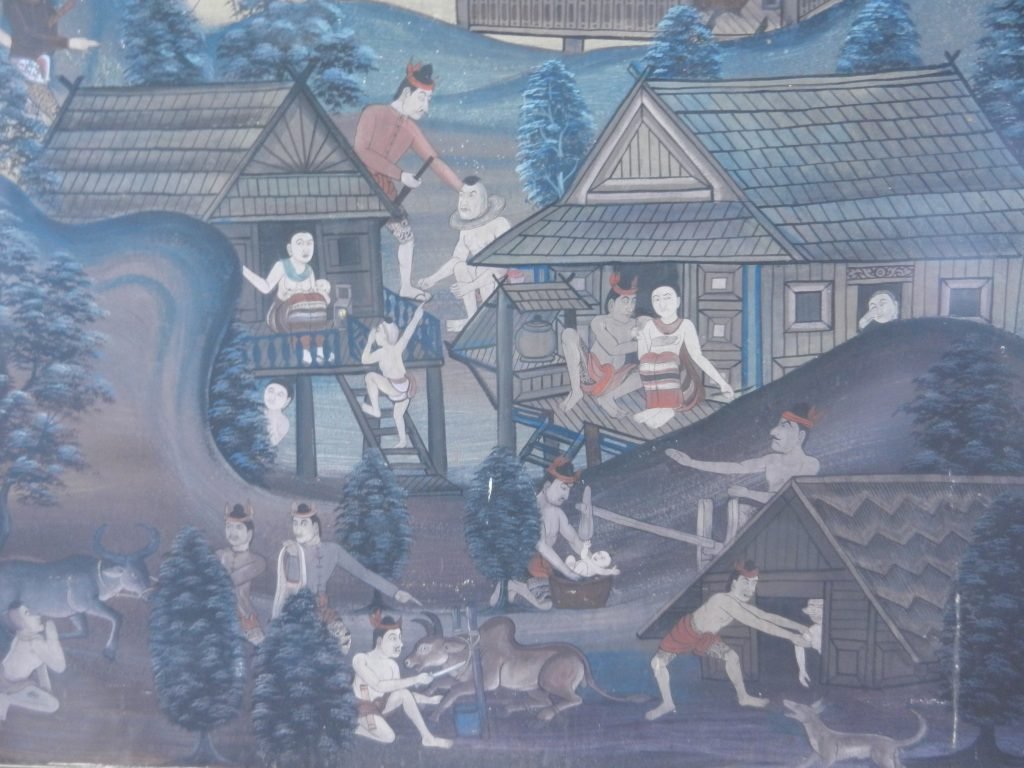

Many fans of northern Thai art admire its human touches. Wat Ming Muang has several scenes of village life. The white and baby-blue colors make the dense and animated foliage more gentle.

Thai art’s known for including humor. A child climbs a ladder (above) while people dance–perhaps in a ritual to promote crop growth.

The dancers and musicians above are having a fine time.

Some of the paintings on the walls inside the vihara also show idealized scenes of village life.

Musicians line the vihara’s outside walls.

They’re larger than the plaques that show daily life. They’re celestial musicians who symbolize more spiritual realms. Their graceful forms and peaceful expressions soften the dense motifs behind them.

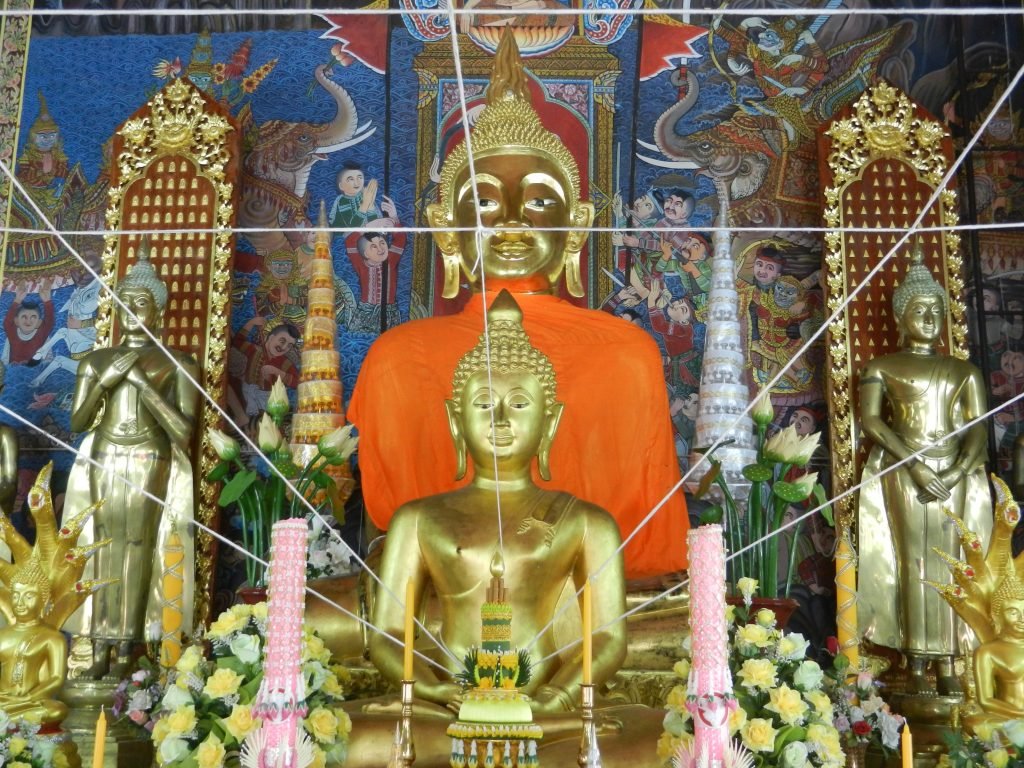

All of these art works guide you to the main part of the vihara, where several Buddha statues on the central altar softly glow on all visitors.

So the whole vihara tolerantly blends the human and spiritual worlds.

I found Wat Ming Muang as good of an example as any other Thai wat of how the Buddha’s compassion and the endless varieties of Thailand’s graceful art forms reflect each other. Some can seem loud, but all are allowed a place within the Buddha’s benevolent gaze. The vihara has enough bombast to attract you, but the tolerant way that all forms mix gently nudges you to expand your ideas of beauty to include all life forms.