Italy boasted many wonders when its artists developed three-dimensional perspective in the 15th century, and no place has been more wondrous than Venice. Its unique environment, a network of small islands off the coast, makes the linear arrangements of arches on the upper-class homes that line its canals seem lilting. Ripples, reflections of light, elegant gondolas, and docking posts softened the lines so that they become more playful.

Being by the sea, clouds and fogs roll in. So the interplays of light shift as the day passes. They also make the canals quickly change hues and moods. Even nature becomes whimsical in Venice. Many people from San Francisco love the place.

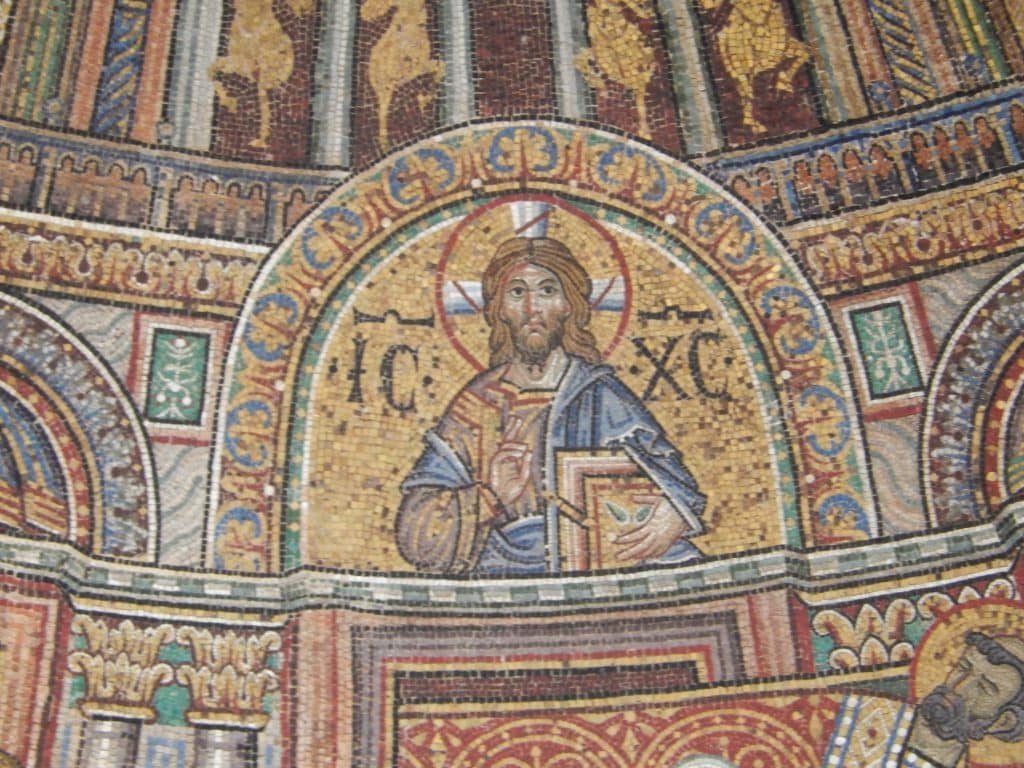

Venice had long-standing economic ties with Constantinople and the Islamic world. Byzantine mosaics shone in several Venetian churches. This one on San Marco’s exterior is a modern reconstruction which is supposed to be authentic. It shows how brilliantly the colors could shine in the sun.

Arabic arches and crenellations graced many of Venice’s buildings, and they added to Venice’s playful light shows.

In the 13th and 14th centuries Venice developed a prolific Gothic heritage, which it showed off on the Doge’s palace’s exterior, which all dignified guest walked by.

It’s leading merchant had traded a lot with Northern Europe, where Gothic style reigned, and many of its churches and upper-class homes were in that style before the 15th century. The 19th-century English art historian and critic deeply admired Venetian Gothic, saying that residents had one of the most refined ways of living at that time. Sensitive connoisseur that he was, he identified six phases that its styles developed in.

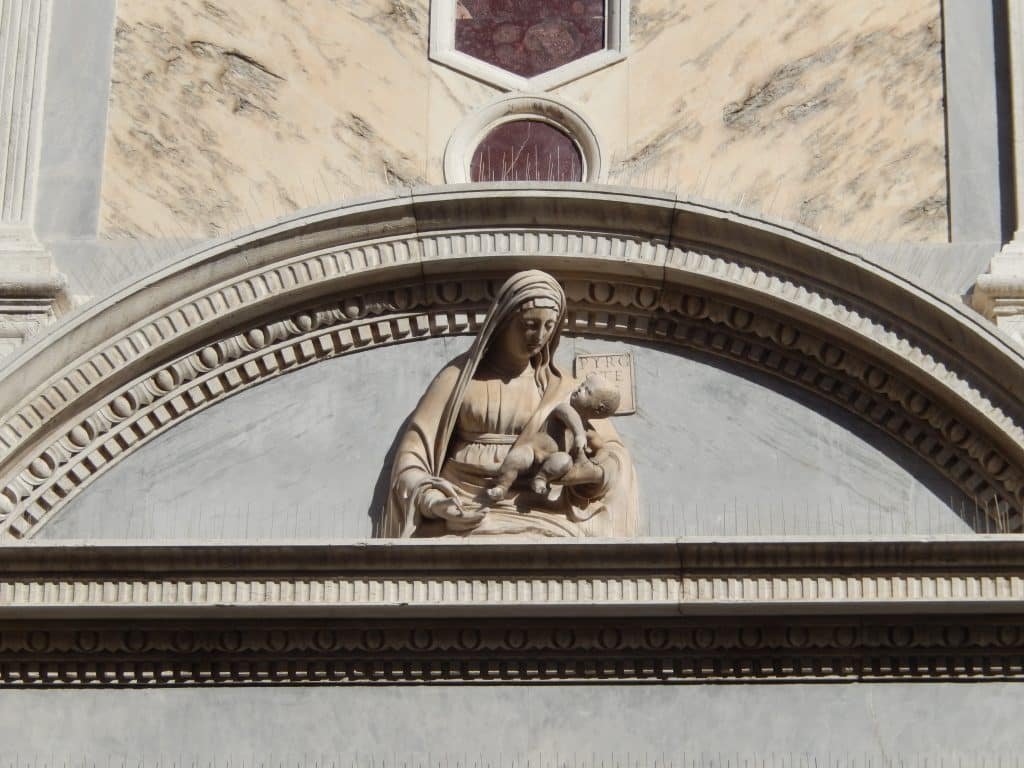

Venetians also used Gothic style to express spiritual aspirations. Graceful arches frame the twelve apostles at the top of the facade of the church of Madonna dell’Orto (the Madonna of the Garden).

These plays of light influenced some of Europe’s greatest paintings, and they were different from what Florentines created. Venice’s artists often treated color as the most basic element rather than the line. Florentine painters usually began a picture by drawing and measuring outlines, but Venetians often started with colors. Florentine painting was more inspired by sculpture and abstract geometry. Venetians were trained from birth to appreciate hues and not hold them second to static shapes and proportions.

Giovanni Bellini was a master of using color to create contrasts so well that art historians have called many of his paintings symphonies of color (below). Saint Catherine and Saint Lucy flank Mary and complement each other, seeming like sisters. On the right, Saint Jerome is absorbed in a book although he’s in the presence of Christ. He looks weathered and pedantic. On the left, Saint Peter holds a closed book and looks pious and contemplative. Behind him a fig tree grows, which symbolizes the cross, since it offers sweet and restorative fruit. The colors of both men’s robes dramatically contrast.

Giorgione blended different shades to create dreamlike glows that made scenes seem mysterious. This has made people over the centuries wonder what those three philosophers below were discussing.

He made worldly beauty mysterious too. This timid-looking young woman, called Laura, reveals one breast and covers the other. The laurel around her symbolizes chastity while the crimson robe evokes passion. Her portrait expresses sensuality and virtue at the same time, and the soft blends of colors heighten the ambiguity.

Titian had an especially prolific career, working well into his eighties (Giorgione died in his thirties). He synthesized all Venetian painters’ techniques and opened up new ways of seeing. In the below scene, the myth of Zeus raping the mortal Danae by disguising himself as a shower of gold is vividly brought to life. Titian made stories that people formerly only imagined as realistic as a photograph.

According to the art historian Kenneth Clark, Titian (1488–1576) was one of the three greatest painters of one of the hardest things to paint well, human skin. Rubens and Renoir were the other two, but since Titian lived first, he was the pioneer. He advanced Western artists’ ability to realistically portray people and depicted them so well that he sometimes exposed aspects of their personalities that they probably didn’t want to be aware of.

One of his subjects was twelve-year-old Ranuccio Farnese. He belonged to an eminent family, which sired a pope (Paul III). Ranuccio became a cardinal when he grew up, largely because of his family’s connections. Titian painted him in an expensive crimson doublet, perhaps alluding to his family’s ambitions (cardinals wore red), but the boy looks uncomfortable playing dress-up. He glances to the side with a somber expression as though he’d rather be running through an orchard, chasing rabbits with a slingshot.

One of Titian’s closest friends was a satirical writer named Pietro Aretino. He was born in Arezzo, where Francesco had painted the scenes of the recovery of the cross in geometrically ordered colors, but Aretino was as far from those frescos’ Platonism as a person could be. He left for Rome but his sexually graphic wit angered so many leaders in its high-strung papal politics that he left town, wandered around northern Italy, and ultimately settled in Venice. The pleasure lover found his home.

Aretino was a connoisseur of everything, and he savored love affairs, art, food, and wine. He and Titian became the center of a group of bon vivants who gathered to enjoy and discuss all of life’s delights. Venice was a perfect city for pioneering explicit worldliness. Titian painted his companion several times and did him justice. In the most famous portrait, a sparkling crimson robe drapes around a mountain of flesh that had imbibed more calories than Milan’s army. A long and bushy beard with glinting grey hairs tumbles to the chest. The large eyes over the hair twinkle, making it clear that he’s eager for more wine and flesh. Titian obviously felt affection for him, and he used color to show a man as grounded in the world as Michelangelo’s David is.

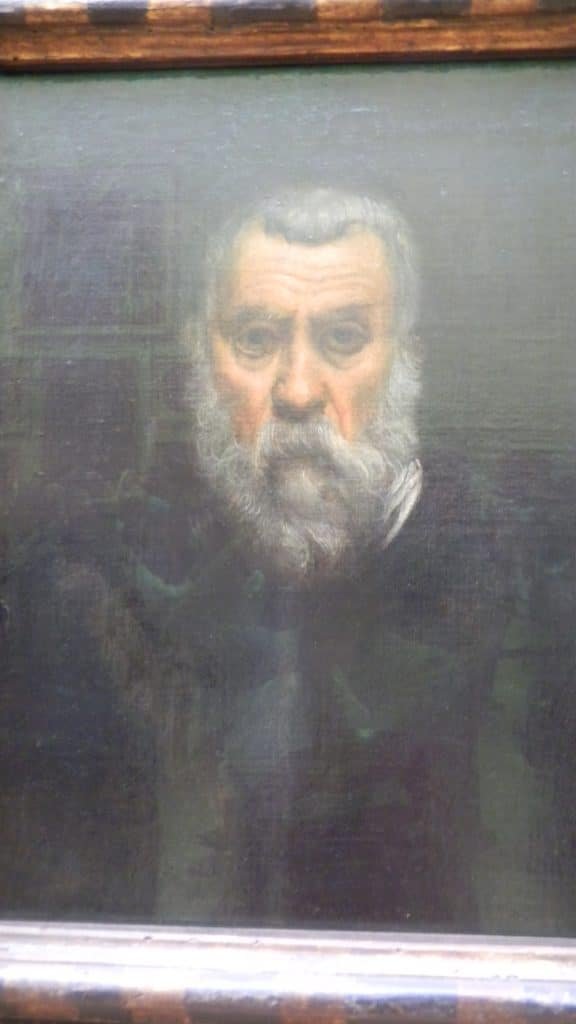

Tintoretto doesn’t seem to have been having such a good time in his self-portrait (below) and he doesn’t seem as fun to be around, but he used color as as masterfully to show emotional intensity. In the mid-16th century, the Council of Trent clamped down on the earlier secularism and declared that art should encourage spiritual devotion.

Traditional Thai paintings don’t reveal the multi-textured skin tones in Titian’s scenes, the inner fire of Tintoretto, or the sinews of Michelangelo’s subjects. They weren’t created to make viewers feel that there’s a distinct individual or a massive body in front of them. Instead, they encourage the eye to mosey in an even flow. Silpa Bhirasri, in An Appreciation of Sukhothai Art, wrote that much of the beauty in Thai paintings is in the expressiveness of their lines.

The outlines of human figures often curve in elegant patterns. The eye can glide over them, and it can meander through scenes at a relaxed pace which doesn’t stop for long periods to analyze the details of any single object. viewers can enjoy the multitude of forms and hues without feeling confronted by any single figure.

Venice enjoyed a building boom in the late 15th century, and architects created designs that made buildings’ forms more rippling than Florence’s sterner focus on lines. The inner yard of the Doge’s palace (in the featured photo) blends Gothic arches with semi-circular arches that Florence and Rome favored.

The late 15th century was a great age of church building in Venice–its leading citizens were hoping that their good fortune would continue forever. They expressed these hopes with beautiful arrangements of abstract lines and arches and gave them soft colors. Santa Maria dei Miracolo (below) surrounds classical forms with them.

This was a local neighborhood church that was associated with Mary’s gentleness.

San Zaccaria (below) is a very short walk from the Doge’s palace.

From a distance its lines seem to command like a caesar. But the arrangements of arches on the upper floors are more elegant as though they’re becoming more spiritual as they ascend. But then a massive arch tops the whole facade as though to say that God’s order over the whole universe is firm and geometrical. Venice was learning lessons from Florence and Rome well.

But up close, its own spirit shows in the pastel colors and delicate inner columns and arches.

These entrancing blends of form and play grace interiors as well, like a music school’s ceiling.

Venice felt like a different world from the rest of Italy as soon as I arrived at its Santa Lucia train station from Milan. The aroma of the salty air and the calls of seagulls seemed more ethereal than the solid earth I had become accustomed to in Rome, Florence, the Viscontis’ stomping ground, and many smaller towns. I spent the next two weeks exploring almost all of the city’s islands, museums, and churches, and thought I had seen just about everything there until I returned five years later.

My first trip was in June, and Venice was baking in a heat wave. But the sky clouded up on the third day of my return visit and the city transformed.

The church domes and steeples which formerly basked in the golden sunshine were now grey, and they barely stood out from the light grey overcast. The canals, boats, and building fronts were all darker too, and all were enshrouded in mists—the formerly clear outlines had dissolved into an atmosphere of intrigue.

The tide peaked on the next day so that the water was lapping over the pavement.

Much of St. Mark’s Square was underwater and people had to wear tall plastic boots to wade through it. The boundaries between land and sea had been breached and everything was at the mercy of nature’s power.

In the late afternoon the tide receded and the sky cleared halfway. The areas where the sun poked through were luminous pinkish oranges, and they hovered over the churches’ domes. The tallest domes seemed close enough to tickle them. The city’s charm isn’t just in its varied buildings and waterways, but also in the ways the weather makes the views and moods quickly change.

Like Florence, Venice established a currency that became one of Europe’s most widely used, the ducat. People from all over Europe traded with its leading merchants, and artistic influences constantly spread into and out from the city. Venice’s and other political states’ arts cross-pollenated each other.

Physical bodies are still elemental in most Venetian art, but much of it is sprightlier than other Italian cities’ paintings and sculptures. Its engaging plays of color added liveliness to the West’s artistic heritage and were sometimes used to make the linear relationships that Florence emphasized seem more real. All main artistic styles in Italy and much of the rest of Europe converged into the West’s emphasis on three-dimensional perspective. All together shaped our ways of perceiving, thinking, and appreciating beauty.

Most tourists in Venice only see a drop of its cultural wealth. But studying its fusions of color and line will give you a lifetime of pleasure. We all have reason to celebrate.

You can also celebrate Indian, Chinese, Southeast Asian, African, and Islamic cultures here.