Djoser’s step pyramid at Saqqara was one of the most dramatic architectural revolutions in world history. There’s no way to overstate its impact. So we’ll explore what makes Djoser’s step pyramid one of the world’s greatest structures.

1. King Djoser reigned from 2630 to 2611 BCE, in the Third Dynasty. His pyramid is more than twice as old as the Roman Forum and the terracotta warriors in China.

2. The pyramid was probably designed by an architect named Imhotep (contemporary records didn’t credit him as its architect). He was made into a deity centuries later.

3. It was erected at Saqqara. It’s next to the capital city, Memphis, across the Nile from modern Cairo, and about 15 miles south of Giza. Saqqara might have been the burial ground for pharaohs in the early Second Dynasty (which started in 2770)–seal impressions with their names were found within two tombs with large sets of underground galleries. Even if the big tombs from that time were only for nobles, Saqqara had already been hallowed before Djoser’s reign.

4. The Step Pyramid was built in six stages. It began as a rectangular single-leveled tomb in a rectangular mastaba form. This was the form that most prior kings’ tombs were in. You can see part of the mastaba in the bottom level in the above photo.

5. Levels were then added to the top to make a total of three and then four.

6. All four levels were then extended laterally, and two more were added to the top.

7. The Step Pyramid’s total height is 197 feet. This was the first skyscraper.

I found it breathtaking to stand in the sands and gaze up at it under the ebullient sun.

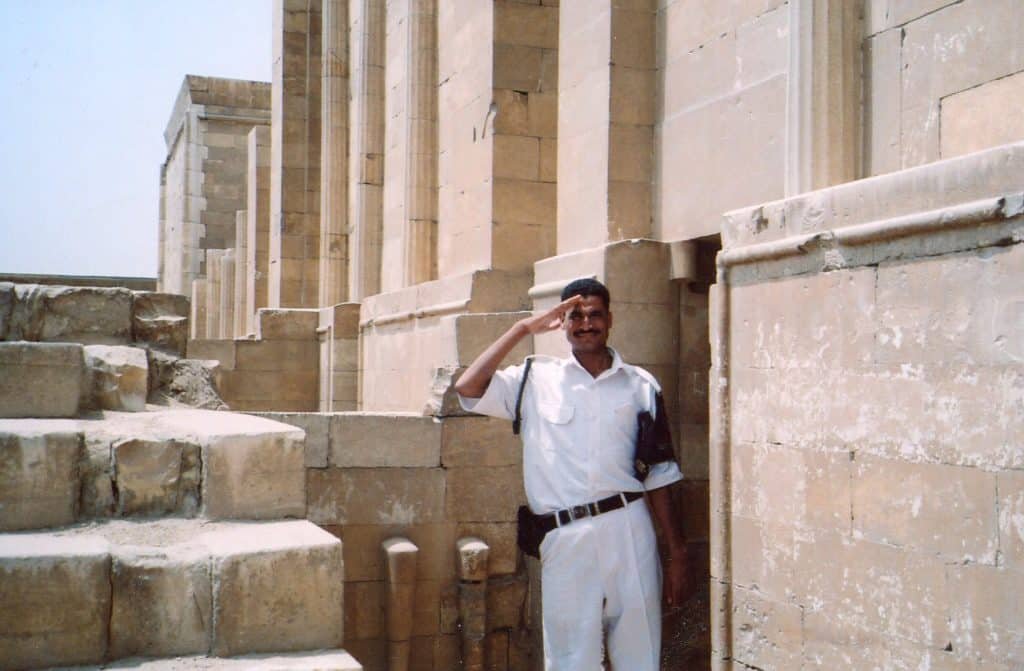

I walked around to the side opposite from the entrance. Gravel was piled up to the top of the first level. Like a little boy, I couldn’t resist climbing. But as soon as I reached the top, a policeman’s voice boomed, “Hello! Close!” I wasn’t going to argue with a guy with a semi-automatic.

But I then walked from that side (the west) to the south side and looked up. Imagine how awestruck people were 4,600 years ago when they marveled at it and had nothing nearly as lofty to compare it to.

But this monument holds many mysteries beneath the surface.

1. A central shaft about 100 feet deep was dug before the pyramid was built over it.

2. Many long underground passageways were dug from the shaft before the single-leveled tomb was expanded into the pyramid. A central corridor and two parallel ones stretch for about 1,200 feet. Three and a half miles of shafts, passageways and chambers were quarried out all together.

3. Rows of blue faience tiles were added to some of the walls where Djoser was supposed to have been buried. Specialists have though that they probably simulated the royal palace.

4. A 34-foot-high rectangular limestone wall was built around the pyramid. It’s 5,400 feet long.

5. The entrance is on the east side, and a line of stone columns leads you in. The stone pillars in this compound were the first ever built in Egypt.

6. The pillars mimic Egypt’s vegetal growth. Older royal halls were made from reeds, so the new stone architecture continued traditions that Egyptians were familiar with. The stone embodied the life that the Nile renewed every year.

7. Enormous courtyards surrounded the pyramid. One was used for the Sed festival, which reenacted the Pharaoh’s coronation. This was repeated at intervals that varied during Egypt’s history. But it was often first conducted 30 years into his reign, and then every three years. It probably renewed the aging king’s energy. Preserving the political and cosmic order was a big job!

8. The newly invigorated king then ran laps between two boundary markers. He might have been following a tradition from pre-historic times in which the leader showed that he was still strong enough to rule.

The underground passageways, the king’s burial chamber, the pyramid itself, and the courtyards and chapels that surround the monument added up to a spectacular location, which was a key center of Egypt’s world in the Third Dynasty. This compound was both a model of order and a battery of energy that sustained it.

The Egyptologist Rainer Stadelmann wrote that the compound was a microcosm of the whole Egyptian state, with a southern tomb associated with the royal burial area down at Abydos and a northern temple associated with the marshy areas up north. The whole compound is oriented to the north-south axis, as the Nile’s flow was. So the complex symbolized the axis of the world and the whole Egyptian state. The pyramid was the central pole of this idealized vision of eternal order.

Its influence extended far beyond Egypt by setting an example for monumental buildings as concentrated centers of meaning. It might seem obvious that a society would do this when it becomes wealthy enough, but not all do. Indians didn’t erect large stone temples until the early first millennium CE. For at least 2,000 years before, they had equally sophisticated cultures, including Vedic which saw ultimate meanings in energies that are distributed throughout the universe. But Egyptians, Sumerians, Greeks, and Hebrews have focused on distinct places with magnificent buildings. King Djoser set an inspiring example for some the West’s most basic assumptions about reality.