What is a circle? Many Westerners have been trained to think of it as an abstract geometric shape with a circumference of 2πr and the Cartesian formula (x – a)2 + (y – b)2 = r2, which outlines its perimeter. Westerners have thus typically conceived of a circle according to its outer boundary, which is static and which defines it as a distinct and permanent entity. But many Indian traditions rooted in the Vedas have defined a circle as the universe’s energy emanating from the center and expanding in all directions. Modern Westerners have usually seen a circle’s outer edge as its most basic aspect, but Vedic followers have often seen the center and expansion of energy that the universe came from as its most definitive aspects. Without this energy, there is no life and there are no conscious beings to define a circle by its outer edge or in any other way.

Chinese ideas of yin-yang and wu xing (the five fundamental processes in nature) have also treated a circle primarily as a flow of energies, but it occurs in a cyclic pattern between equally significant domains rather than outwards from the center. The I Ching’s hexagrams have also been arranged in this kind of circuit; all the primary patterns in nature that they symbolize transform into each other in a recurring cycle.

People in many traditional African cultures have seen a circle as a community of members in dialog. Many Yoruba people have imagined the universe as shaped almost like a circle (as a gourd), with gods and spirits in the upper half, humanity in the lower, and constant interaction between both areas. The circular hut is one of the most common forms of traditional domestic architecture in Africa. Many of the most intimate human interactions occur within a circle. People have thus grown up thinking that human relationships make up the essence of a circle. The abstract perimeter lacks life.

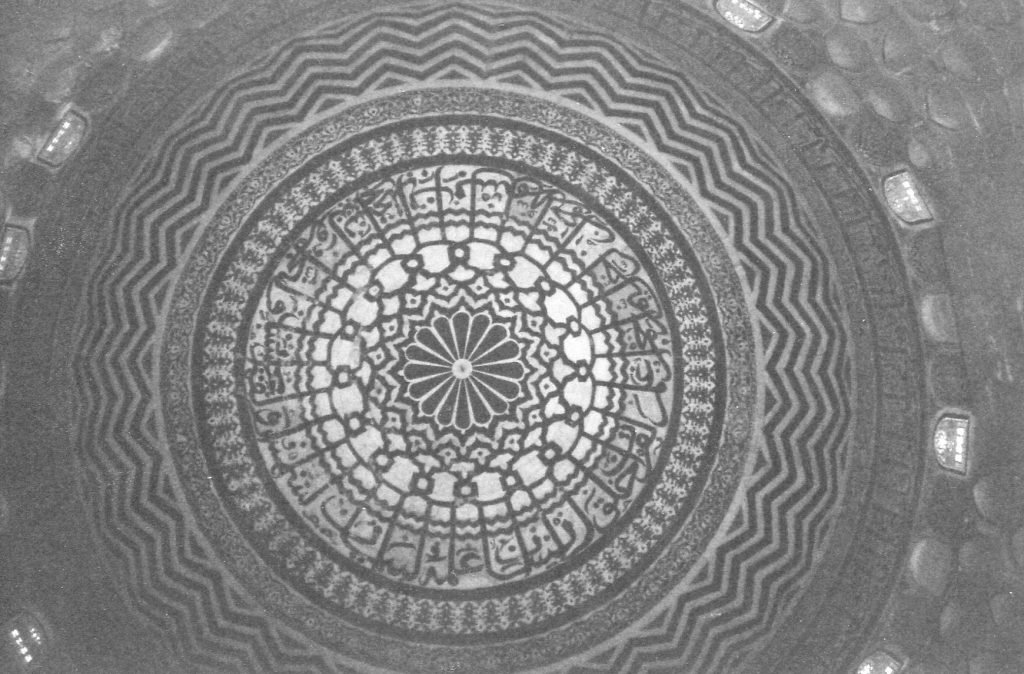

A lot of Islamic traditions have considered the circle’s center more primary than the outer perimeter.

God creates from the center, establishing the main divisions in nature, as the above ceiling in a Cairo mosque shows. The energies that enable growth then issue forth. The foundations of civilization are then developed, including writing, which you can see in one of the middle layers.

The Oglala Lakota holy man Black Elk told the poet John G. Neihardt, “You have noticed that everything an Indian does is in a circle, and that is because the power of the world always works in circles, and everything tries to be round. In the old days when we were a strong and happy people, all our power came to us from the sacred hoop of the nation, and so long as the hoop was unbroken, the people flourished. The flowering tree was the living center of the hoop, and the circle of the four quarters nourished it. The east gave peace and light, the south gave warmth, the west gave rain, and the north with its cold and mighty wind gave strength and endurance.”

Black Hawk continued, “The sky is round, and I have heard that the earth is round like a ball, and so are all the stars. The wind, in its greatest power, whirls. Birds make their nests in circles. The sun comes forth and goes down again in a circle. The moon does the same, and both are round. The life of a man is a circle from childhood to childhood, and so it is in everything where power moves.

Our tipis were round like the nests of birds, and these were always set in a circle, the nation’s hoop, a nest of many nests, where the Great Spirit meant for us to hatch our children. But the Waischus (White Men) have put us in these square boxes. Our power is gone and we are dying.”

So a seemingly basic idea like a circle can reflect the whole cultural landscape that encourages its members to treat one of that shape’s aspects as its most fundamental. In The Way We Think; Conceptual Blending and the Mind’s Hidden Complexities, Gilles Fauconnier and Mark Turner said that what we call a concept is actually a mixture of several ideas. Westerners have inherited the tradition of thinking that a concept is a platonic entity; it’s singular, distinct, and permanent like a Greek temple or a Euclidean geometric shape. But each concept integrates a unique mixture of experiences, and the whole culture influences the blend.

The most probable locations of electrons in the orbit around the atom’s nucleus have been seen seen as progressing in a circle since Niels Bohr developed a model of the atom which resembles a system of satellites traveling around a planet. But this idea doesn’t convey all the meanings in Chinese, African, Islamic, or Native American concepts of a circle. What ideas do you find most meaningful? That largely depends on your culture and personality.

We can increasingly see our concepts as convergences that have emerged in a highly multifaceted and limitlessly fertile society with several past eras and many connections with other cultures and with its own natural environment. We can uncover ever more riches in our ideas by looking At/With/Beyond them to savor their histories and reflections with other cultures’ ideas. We can thereby find more richness in ideas rooted in ancient Greece, China, Africa, the Islamic world, and Native American societies. We can also explore others, including India, Thailand, and Cambodia.

As we continue to look At/With/Beyond concepts that are treated as basic, we can enjoy a never-ending journey around the world, which can enable us to see all cultures as shining on each other.