Westerners have often assumed that creating images is about mimesis–realistically imitating what people see in the physical world. But other cultures have created images according to different assumptions.

Ancient Indians’ appreciations of abundant cosmic energies inspired them to develop conventions for expanding images of gods way beyond what is physically seen. Vishnu has his four arms and hands in which he holds a disk, a conch shell, a mace, and a flower.

His incarnations into a boar, turtle, and man-lion, which enlivened India’s narratives, did the same for its visual culture as they were portrayed in sculpture. Brahma’s four heads face the cardinal directions so that the god who created the world can see everything in it. He has four arms and hands, which hold two ladles used in sacrifices, a string of rosary beads, and Vedic texts. Shiva dances within a ring of cosmic fire, and his long hair flings outwards as he gyrates. Harihara is a fusion of Vishnu (Hari) and Shiva (Hara); one side of his sculpted image is of Vishnu and the other half is of Shiva.

The elephant-headed god, Ganesh, became popular in Hindu mythology. He was guarding his mother, Parvati, who was Shiva’s wife. Shiva returned home one night, so the dutiful son, unable to recognize him in the dark, tried to prevent him from entering. Shiva didn’t recognize him either and sliced off his head with his sword. Parvati was devastated, so her husband vowed to replace the head with the first one he saw. An elephant passed by at that moment.

Several Hindu deities ride a certain animal, and Ganesh’s mount is usually a rat (sometimes a mouse). Opposites (the majestic and pesky) are thus unified. A rat or mouse can scoot through walls, and this idea of overcoming all obstacles became associated with Ganesh, so he has been popular with businesspeople. Rats and mice also breed quickly, so he has been associated with their fertility. He has a sweet tooth, and in standard sculptures, the end of his trunk forages through a little candy dish as he feeds his ample paunch.

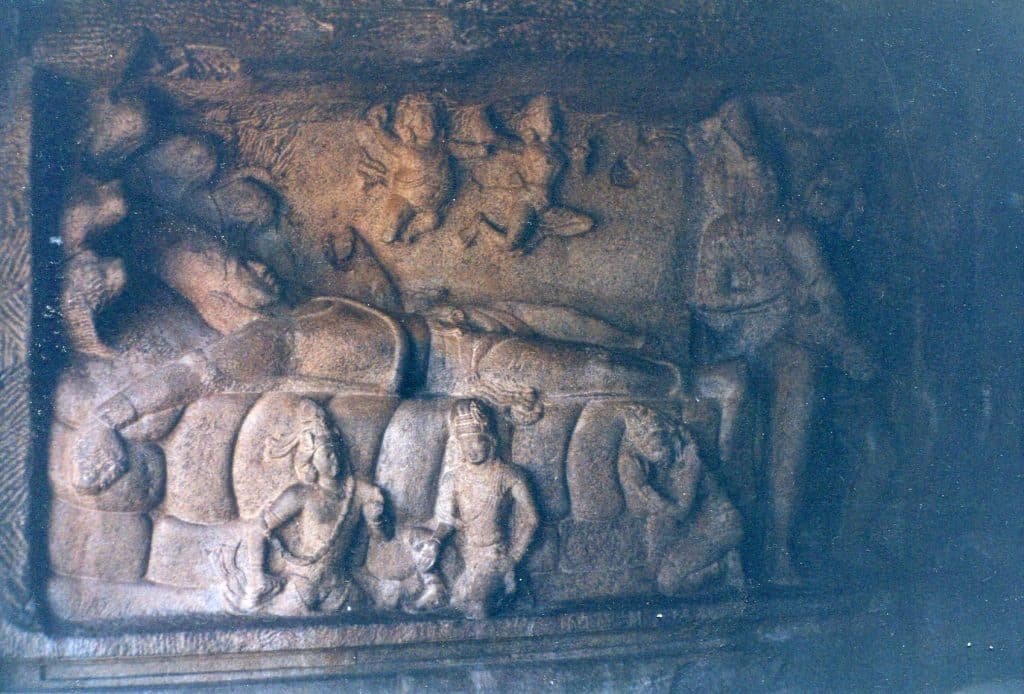

Indians’ imaginations leaped far beyond the realism in Greek and Roman sculpture, and artists made their pantheon of gods reflect the universe’s abundance. Sculptures and paintings of an enormous panorama of life forms adorned the temples that people were building. Below, Vishnu sleeps on a giant serpent before the universe begins a new cycle of creation.

Ancient Indians also expanded temples into many levels. Each could house lots of sculptures of different incarnations of gods. This reinforced the tendency to imagine a large number of deities’ manifestations and create images of them.

The Shilpa Shastra is a collection of texts about how to create sacred images. Following the Upanishads, they say that the universe is permeated by a primary substance which is beyond thought, sensory perception, and words. It’s the source of all manifestation, growth, and movement. Sculptures are not supposed to be realistic portrayals of bodies and faces as people normally see them with their eyes; those are dense material manifestations of something more primary. Sculptors are supposed to portray beings closer to the source of creation so that the images are idealized. The Shilpa Shastra details the correct proportions, facial expressions, postures, movements, and other iconographic elements for depicting a more primary world than what we apprehend with the five senses. The images are stylized rather than individuated.

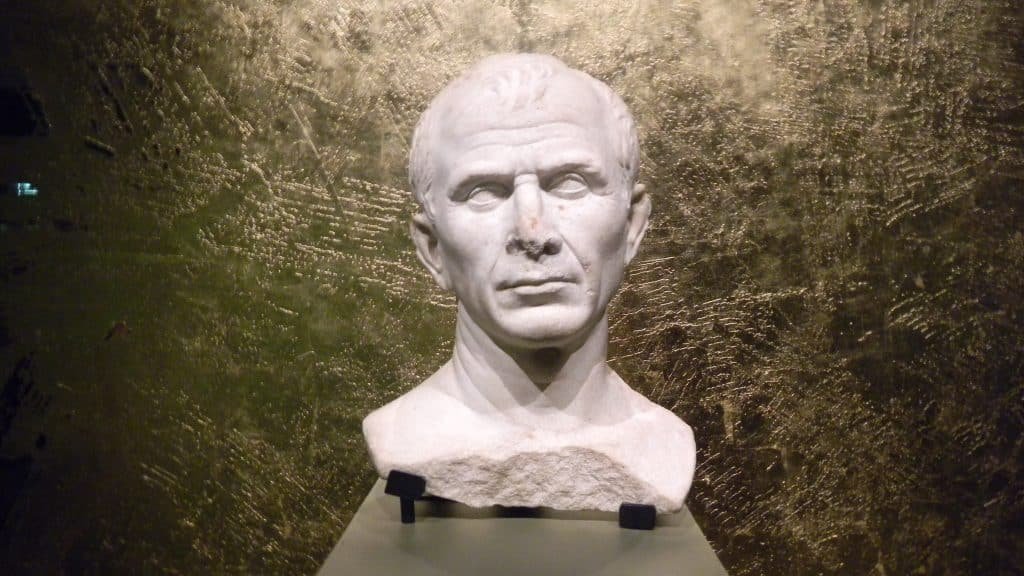

Kings followed these standards while representing themselves. There are no ancient Indian equivalents of a Greek or Roman political leader realistically portraying himself. No Alexander the Great projects unbound restlessness. No Julius Caesar (pictured below) comes across as the meanest SOB ever born to convince Celts in France not to rebel again.

No Pompey the Great shows his peasant-like broad face and unruly hair, posing as a man of the people and distinguishing himself from Julius Caesar’s imperialism. And no Emperor Vespasian, a former general in North Africa, expresses his soldierly commonness by being portrayed with a stressed-out facial expression that looks as though he’s struggling to have a bowel movement. Indian kings displayed themselves as idealized figures before the Persian and Turkish influences in the Islamic courts that began to rule from Delhi at the beginning of the 13th century. Kings and Brahman priests had buddied up since Vedic times, and both followed the same aesthetics while representing the most honored things and patterns in the world. They portrayed them as idealized and connected with the vast cosmos.

This way of creating images emerged and has remained prominent because it converged with many other aspects of Indian culture. Ancient Indians felt that the meaning of images comes from the whole universe’s metaphysical field, while Westerners have located the meaning in the objects that are portrayed and their immediate surroundings. Both cultures have developed equally creative traditions based on their assumptions.

Ancient Chinese had other assumptions about creating images. We’ll shortly see that Africans have too.