Vietnam is full of underappreciated cultural blends.

China had ruled Vietnam since 111 BCE. The Vietnamese finally gained independence in 939, after China’s Tang Dynasty disintegrated. During the more-than 1,000 years of Chinese domination, elite officials imported:

1. Confucian ideas of the central importance of male-dominated traditions in the family and political institutions.

2. The Chinese script.

3. Chinese art forms in architecture, ceramics, music, and painting.

These Chinese traditions had blended with local Vietnamese cultural patterns such as:

1. Looser political structures, which allowed more independence for women.

2. Local spirit cults.

3. Appreciation of Vietnam’s natural environment, including abundant lifeforms, majestic mountains, and beautiful rivers and beaches.

4. Artistic traditions that tame the vibrant natural environment with soft colors.

Since these fusions happened over more than 1,000 years, they were deeply ingrained. So the two great Vietnamese dynasties that flourished before Ming China invaded again and ruled briefly in the 15th century, the Ly (1009-1225) and the Tran (1225-1400), continued them. Both mixed Confucianism, Buddhism, and local traditions to unify the land.

As I rode bikes and walked through towns, I kept finding fusions that I had never heard of.

Two of the above three photos are of a restored gate in Hue’s 19th century imperial palace: the gate of the Truong San Residence. The Nguyen Dynasty built the palace to project a model of Confucian rule after a long three-way civil war raged throughout Vietnamese lands. It’s design thus follows Beijing’s Forbidden City, with a rectangular system of courtyards, public halls, an inner court, and walled compounds for temples and private residences. But these hallowed forms blended with the local culture into a more Vietnamese outlook.

The gate is basically Chinese in form, but its color scheme is full of tones that are both soft and cheerful. I found the pale yellows and blues easier on the eye than China’s commanding reds.

The gate is modeled on Beijing’s Forbidden City’s south entrance’s horseshoe design.

Its upper floor gave emperors and their entourage an elegant place to preside from.

The great halls are lower than the ones in Beijing’s Forbidden City. They’re more in harmony with the earth rather than trying to dominate all the surroundings.

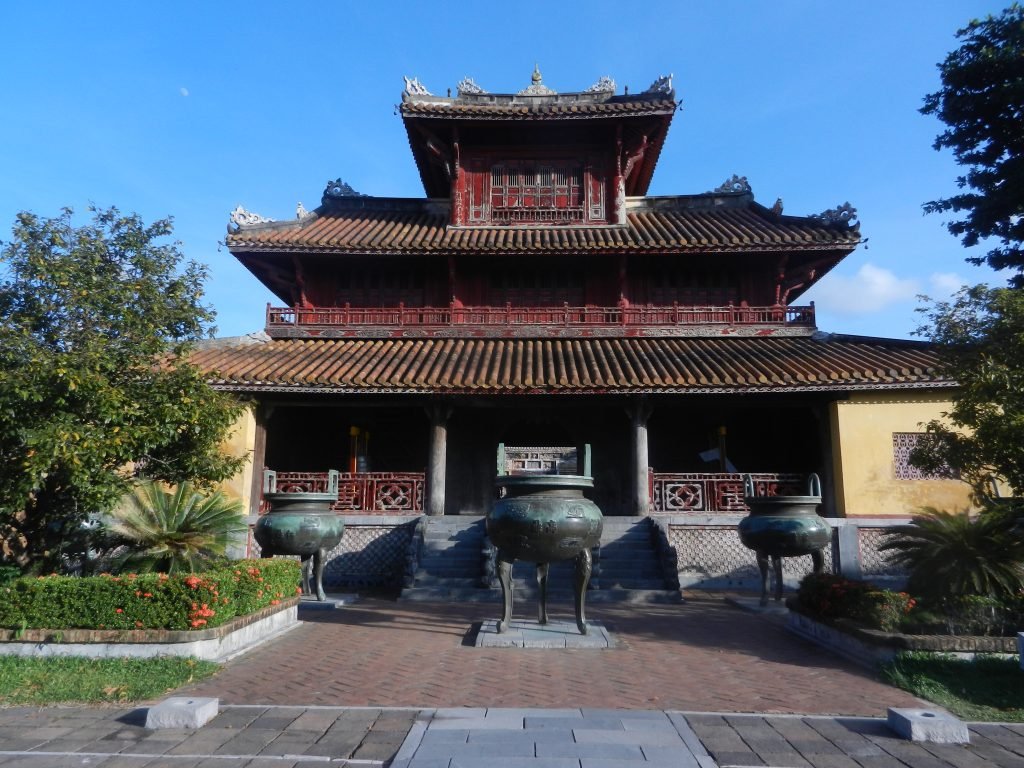

Rituals that glorified the kings were regularly conducted in these halls. The above shot is from the Mieu, which contains a long line of red lacquer and gilded alters to 10 of the 13 Nguyen emperors and their queens, beginning with Gia Long, who founded the dynasty in 1802. Another stately hall, called Hien Lam Cac (below) was the Nguyen’s hall of fame.

Nine bronze urns, which represent nine Nguyen emperors, line its front. The middle one is the largest and most important; it honors Gia Long.

Its makers thus carved its details with a lot of care. Confucians and Daoists deeply honored the tortoise in ancient China, associating it with the universe, longevity, and wisdom. More than five centuries before them, Shang Dynasty kings used it for divination. The many waterways and the monsoons in Vietnam made it easy for locals to blend their appreciation of their own natural surroundings with Chinese traditions.

Court music, dance, and theater were integral parts of the palace’s ritualized atmosphere. Gia Long’s successor, Minh Mang, built the theater next to the royal halls in 1826.

Women sat in the upper balcony that begins on the left; it flanks both sides of the hall.

Male audience members displayed themselves on the ground floor.

These girls are keeping the blends of Confucianism and local elegance alive.

The western side of the palace area had several compounds for royal family members. The largest, Dien Tho, was the queen mother’s and grandmothers’ quarter. The honored women presided against the back wall in the below photo.

They relaxed at the Lily Pond and Pleasure Pavilion outside.

Other western compounds had gardens to stroll in.

The Nguyen emperors created an ethereal place to rule from, but the realm was more diverse than they wanted to admit. The ancient Cham culture ceased being an independent state in 1832, but it previously created some of the most refined art ever made in Asia or anywhere else. The port town Hoi An (below) was a bustling community of traders from many countries, which contrasted with the perfume-scented world that the emperors lived in.

We’ll explore dynamics between different cultures in Vietnam in the next article.