After the first known Greek philosophers (in Meletus) speculated about the basis reality, Parmenides and Empedocles expanded mental horizons further beyond the visible world of the agora and harbors. Others did as well, but all retained and reinforced thinking that was characteristically Greek, and they strengthened Western thought’s orientation to distinct entities, linear relationships between them, proportion, and vision.

Pythagoras emigrated to southern Italy from Samos (an island off the southwestern coast of Turkey) and governed a community in a town on the ball of Italy’s foot, called Croton. His followers set themselves apart from others to purify their souls and were fanatically secretive, but they were famous for believing that souls reincarnate into many species. Since Pythagoreans saw all living beings as akin, they were vegetarians.

No original writings from Pythagoras exist, but he is credited with seeing ratios between whole numbers as basic in the world’s order. According to Aristotle, some of Pythagoras’ most influential followers said that there are ten pairs of principles in nature:

Limit and unlimited

Odd and even

One and many

Right and left

Male and female

Resting and moving

Straight and curved

Light and darkness

Good and bad

Square and oblong

Aristotle wrote that they taught that the former principles are good (agathon) and that the latter are bad (kakon), because limits and stability are preferable. C.S. Kirk, J.E. Raven, and M. Schofield, in The Presocratic Philosophers, wrote that Pythagoreans found static geometric shapes appealing, because each shape makes otherwise unlimited space fathomable and easy to see (the male-female distinction was probably included because many ancient Greeks associated masculinity with strength, solidity, and control). They thought that the cosmos is surrounded by a limitless amount of air or breath, but focused on limits, stability, and mathematical ratios, which guarantee fathomable order within the boundlessness.

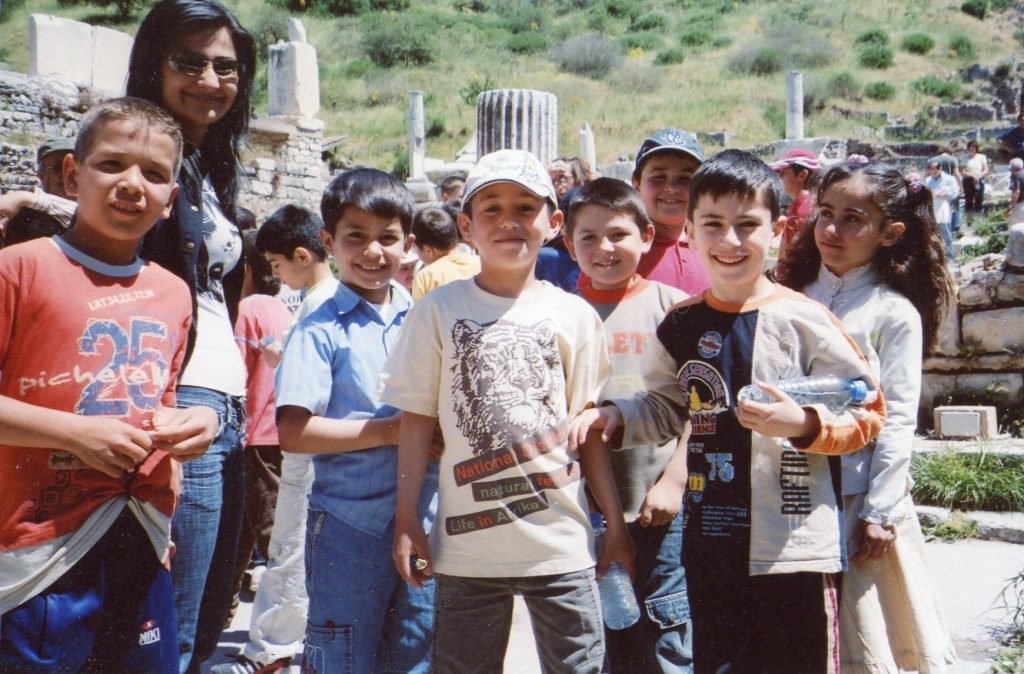

Other early philosophers also saw the unity of nature in terms of limits, proportions, and distinct entities. Heraclitus lived in Ephesus, which was a prosperous coastal city north of Miletus (the young thinkers below greeted me in the town’s remains).

He expressed low opinions of other people many times and complained that they failed to understand him, that they didn’t use their intelligence or senses correctly, and that they cared more about stuffing their stomachs like cattle than learning about truth. According to one anecdote, fellow citizens found him playing dice with children, and when the adults asked him why he retorted, “Isn’t this better than playing politics with you?” Disdaining his society’s conventions, he is supposed to have said that everything flows (panta rhei), and he asserted that the universe is an ever-active fire.

But he expressed the primacy of change and fire with several conventional Greek philosophic ideas that focused on proportion and tangible objects. He said that all things come to be and perish according to a rational principle that orders the relationship between fire and what emerges from it. Fire is kindled and goes out in a measured way (metra). All things are an equal exchange for fire, and fire for all things. He called the exchange antamoibe, saw it as proportioned, and likened it to the trading of economic goods for gold and gold for goods.

Fire turns into sea, and half of sea then turns into earth and half into a fiery windstorm or lightning (prester). The portion that becomes earth turns back into sea in the same quantity it was in before becoming earth. Some historians have surmised that prester thrusts upwards and becomes the heavenly bodies, which then turn into fire. So Heraclitus saw the reality that emerges from fire as visible, tangible, and proportioned. And the transformations from fire to other types of existences and back into fire are in measured quantities.

He has also been famous for thinking that opposites are unified. This sounds Indian on the surface, but he envisioned this unity, not as a field like brahman, but in physically tangible terms. He said that a strung bow or lyre depends on tension between two forces pulling the strings in opposite directions. He called this tension tonos, and objects’ identities and functions depend on a perfect balance between the opposed forces. Objects are not constituted by the copious Vedic flows of energies, but by agon (competition) between equal forces pulling in opposite directions. Heraclitus said that war is the father and king of all, and that all things happen in accordance with strife and necessity. What we conventionally think is stable and at rest is really the outcome of a constant struggle between opposing forces of equal strength. This continuous warfare is regulated by measure and proportion, which give the things in the world stability in the midst of its ceaseless change. Day & night, heat & coldness, physical activity & rest, and hunger & satiety are meaningful in terms of each other; they exist as equal opposites in a continuous tug-of-war.

Anaxagoras came from a town in western Turkey near Smyrna, moved to Athens, and became a prominent thinker there. He grew highly influential as a mentor to the statesman Pericles and the philosopher Archelaus of Athens, who was one of Socrates’ teachers. Anaxagoras is credited with saying that the cosmos began as an infinite number of infinitely small things, which each contained a portion of all the others. This unified and infinite field sounds Upanishadic, but Anaxagoras imagined the early universe according to concepts that Greeks were emphasizing.

The cosmos was set in motion by mind (nous), which is self-ruled (autokrates) and pure (katharos). Mind began to rotate the universe, and the rotations caused the dense matter to be separated from the rare, the hot from the cold, the bright from the dark, and the dry from the moist. Instead of the Rigveda’s rich stock of ideas of vastly flowing energies (e.g., jyoti, prakasha, praketa, ruc, bhanu, ojas, mahas, sahas, savas, vac, vayu, and several others), Anaxagoras saw the universe’s first manifestations in terms of a pure mind and as opposite qualities in things we can observe. The idea of proportioned oppositions had already been emphasized by Heraclitus, Empedocles, Anaximander, Hesiod, and the Homeric poems. He adapted this tradition and added the idea of mind as the governing principle over everything.

He continued his account of the creation of the universe by using another concept that reflected Greece’s cultural and natural landscapes. If the universe was initially undifferentiated, with a portion of each thing in every other thing, how did the sun, stars, moon, living organisms, and other objects come to be? In this unified field were seeds (spermai) of the qualities of all things that have existed, and spermai that were the most alike attracted each other (some historians of philosophy have thought that the seeds, rather than an infinite number of things, are what contained a portion of each other in the early universe). So hot and dry things attracted each other, and firm things also began to coalesce. As like continued to attract like, fleshy substances congealed and further differentiated into living beings. All things (or seeds) still contain a portion of all others, but some attributes now predominate in each. Something is fleshy or hot if flesh or heat is a main attribute. As different seeds separated and similar seeds attracted each other, the earth was solidified, stone was solidified, and water was separated from clouds. The proportioned natural environments that Greeks lived in were formed. As like was attracted to like, the heavy gravitated to the center and the light moved towards the circumference of the universe as it whirled.

So for Anaxagoras, it was a short mental step from an initially infinite universe with a portion of each thing or seed in every other to a mechanical process in which things become more differentiated and were established in their own domains. Rather than emphasizing subtle energies that profusely flow and which are seen with the inner eye and heard with the inner ear, he focused on the visible world, perceivable objects and processes, and a pure mind that orders them.

The atomists Leucippus and Democritus saw the world as consisting of an infinite number of imperceptibly minute things, which they called atomai (the word’s literal meaning was indivisible). They’re not infinitely small, as Anaxagoras might have seen the tiniest portions of things. Instead, they’re in many different shapes and they move within an infinitely vast field. They randomly collide, and the ones with similar shapes stick together. Atomai with hooks latch onto each other and become the dense matter we can feel. Smooth ones slide by each other and become water and air. The various positions of atoms on the surfaces of objects reflect light in different ways and thus enable us to see colors. Even people’s and animals’ souls are collections of atoms, which are the finest and most spherical, and thus the most mobile.

Leucippus and Democritus did step more fully into thought that was more common in India by holding that there are innumerable worlds within an infinite void. Some worlds have no sun or moon, in others they are larger than the ones in our world, and in others they are more numerous. Intervals between worlds are unequal; in some parts more worlds exist and there are fewer in other areas. Some worlds lack living creatures, water, and moisture. Some are increasing in size, some are at their peak, and others are disintegrating. Kirk, Raven, and Schofield wrote that Leucippus and Democritus were the first Greek thinkers that we can attribute the concept of innumerable concurrent worlds (as opposed to worlds that succeed each other) with absolute certainty to. So this amount of abundance wasn’t a common concept among the pre-Socratics, and Leucippus and Democritus still focused on atoms as distinct objects and the mechanical processes in which they move.

The Milesians (Thales, Anaximander, and Anaximenes), Parmenides, Empedocles, Pythagoras, Heraclitus, Anaxagoras, Leucippus, and Democritus expressed ideas that can seem mystical in terms that resonated in Greek culture. The physical landscape, politics (e.g., the rise of the city-state and the emergence of colonies), the use of money, the alphabet, Homeric literature, Hesiod’s poems, art, architecture, theater, and athletic games resonated with each other and converged into a widely shared way of seeing the world as philosophers began to think about the basis of reality.

They taught and debated by using ideas that reflected those experiences. Concepts of proportion, distinct and visible objects, limit, primary opposites, and abstract geometric shapes coalesced into a common stock of ideas that thinkers and their students used in their speculations and discussions.

Other experiences converged into different ideas in other cultures, including Chinese, Native American, African, Islamic, and Southeast Asian. Ideas that a culture treats as basic aren’t atomic objects. They converge in a field of experiences with many dimensions, and each culture is unique.