Ancient Greek cities were engaging in unique ways. They were so immersive that it was difficult for most people to imagine life outside them, and this made Western thought different from Indian and Chinese. We’ll explore a few here.

I flew from Istanbul to Smyrna, where Homer was said to have lived. The modern city Izmir was built over the ancient ruins. I hired a driver at the airport, who took me to the first fairly well-preserved ancient Western city I ever saw, Pergamum. As we motored north, the sea sometimes came into view. The dramatic contrast between water and clear coastline was a fitting prelude to my first trip to an ancient Greek community.

In the third century BCE, Pergamum repelled an invasion by my own ancestors, the Celts. The latter had expanded from the north in the fourth and third centuries and terrorized the northeastern and northcentral Mediterranean. They even sacked Rome. Many Greeks and Romans saw them as wild as jackals. In battle they sometimes put on war paint, shagged up their hair, and brought their women to cheer them on. They also drank wine undiluted. Pergamum’s king Attalus I (r. 241–197 BCE) drove them away. The city’s leaders were elated to be rid of those seemingly feral creatures, and they looked to Greek aesthetics to build a model city as a bastion of civilized life.

We drove up to the acropolis, which is about 1,000 feet above the valley floor. The kings crowned the highest part with the most prestigious buildings, including the royal palace, a temple for Athena, a library, and a famous altar that Germans took to the Pergamum Museum in Berlin in the late 19th century.

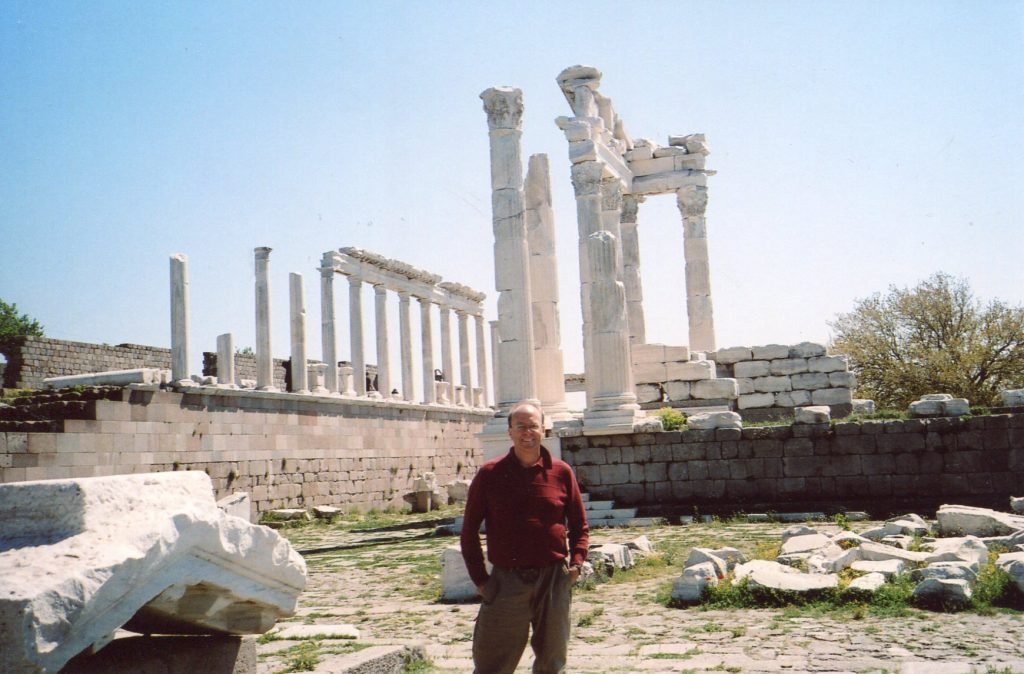

All constructions were human-scale, including the palace, which was built around two modestly sized courtyards. The area resembled cityscapes all over the Greek world; distinct buildings were handsomely proportioned, they stood out from each other as though they were in dialog. The building below is Roman (the temple of Trajan), but its colonnades and clear lines descended from Greek architecture.

They were exquisitely balanced with open spaces. But my next experience moved me even more.

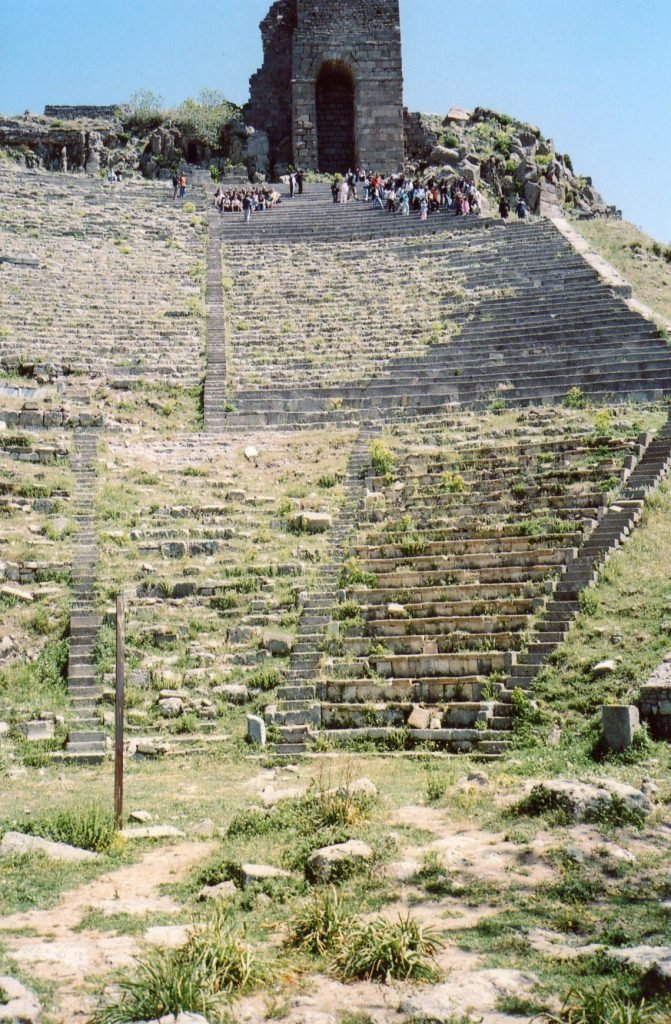

An enormous and unusually steep amphitheater was built into the mountainside just below the summit. I slowly descended, sometimes sitting down to imagine how people back in the day felt, and saw another dramatic contrast.

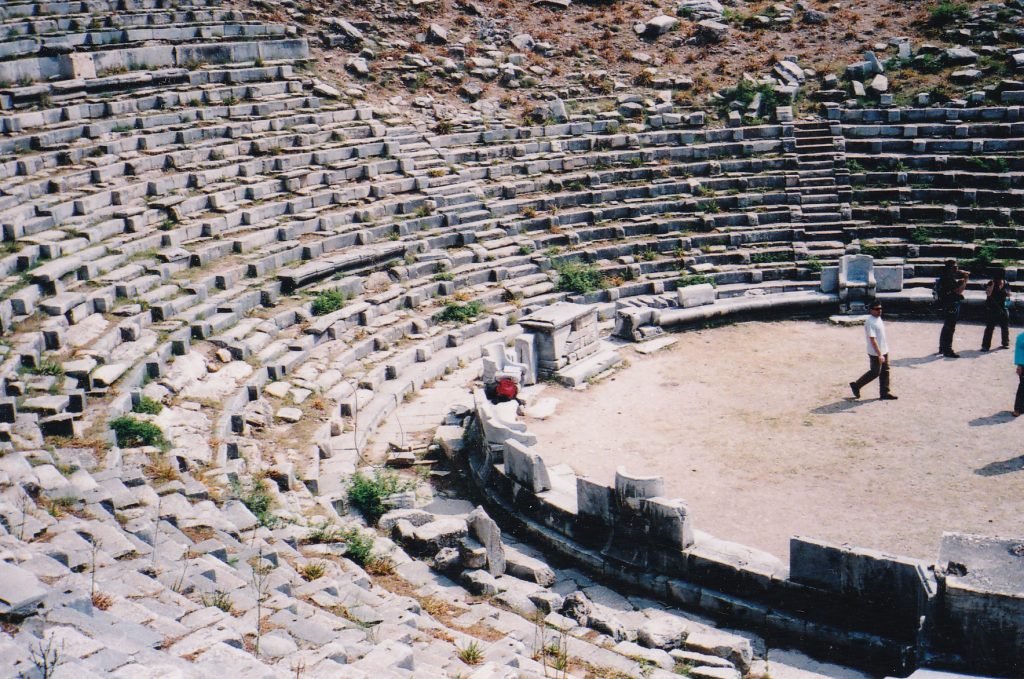

I peered outwards, over the valley below and to slopes facing me from its other side. The hillsides were steep and craggy, and thus seemingly hostile to life. As I scanned, my gaze came back to the rows of seats on the other side of the theater (above). The ancients probably experienced a sharp distinction between wild, unformed nature and the intimate community nestled in the theater’s embrace. As in other ancient Greek amphitheaters, people savored views of each other during performances. A profound feeling of belonging overtook me.

This feeling deepened when I reached the bottom. A little to the right of the stage was a small temple for Dionysos. Its ground plan was rectangular and the remains of one column jutted upwards.

I walked into the temple’s remains, turned around, surveyed the amphitheater just beyond its column, and felt even more nestled in a proportioned civic community. It seemed that I had been there before. The experience was like returning home after a long day at work, walking through your front door, closing it, and settling into your living room with your favorite comfort food. The surroundings felt familiar and warm. An elderly American man that I met three days later said that he had the same experience in ancient Greek cities. The handsome proportions can make you feel deeply immersed in the spaces they form.

But I soon experienced a less pleasant aspect of the ancient West. The next day, my driver took me to Ephesus, which was one of the greatest cities in western Turkey for 1,000 years. Heraclitus lived there around 500 BCE, but most extant constructions were built by Romans after they took over in the second century BCE. I sat in front of the two-story edifice of the library, which an official under Emperor Hadrian built (shown below). This is Ephesus’ most famous building, with elegant vines carved between slender Ionic columns. But pictures of the facade don’t reveal what the whole area was like.

I sat with the library on my left and gazed over the public square in front of it, which was one of the town’s busiest places in ancient times.

In front of me was a sturdy three-arched gate built to honor Emperor Augustus in the early first century CE (above), and on my right was a complex of public buildings which housed a brothel. The better preserved city of Pompeii, which I explored in the following year, had about 20 brothels, and its largest still stands in the corner of a Y intersection (below).

So in both cities, many people could see who was going in and coming out. Streets and public squares in both towns must have been livelier than our antiseptic shopping malls and high-tech business parks. Yes, they were often intimate and warm, but people were always watching each other. The stones are now mute, but gossip, cat calls, and arguments were common around them, and they sometimes became violent. I ended up feeling confined in Ephesus and realized that I would have been restless to escape if I had lived there.

An Ephesian poet from the sixth century BCE expressed other intense aspects of town life. Hipponax became such an expert at composing abusive verses that his insults are supposed to have driven two sculptors who made fun of his homely face to suicide.

He and a predecessor from the previous century, named Archilochus, developed a verse called iambic (limping), whose irregular rhythms contrasted with the dignified steady beats of Homeric poems. Archilochus pioneered the use of poetry to insult people who angered him, and he was also said to have driven some of his targets to suicide. Many modern readers have seen him as a rebel. Forced by poverty to find better fortune on another shore, he became a settler and sometimes soldier on the island Thasos. But he expressed disdain for the Homeric models of heroism by boasting that he threw his shield away to escape death on the battlefield. That was shameful according to Homeric values, which made honor centrally important, but he declared that he could find another one.

And presumably savor many meals between the battles. Hipponax retained Archilochus’ love of favoring everyday experiences over the heroic by detailing food. The voice in one poem was of a man reduced to peasants’ fare by a profligate son. He had to live on tuna fish, cheese, barley-wheat loaves, and under-sized figs, and complained that he could no longer enjoy partridges, hares, pancakes with sesame, and fritters dripping with honey. He also referred to the opposite end of the digestive process, once comparing someone to a raven cawing on a toilet.

Sappho of Lesbos wrote about more refined scenes and feelings. She portrayed herself as a member of a circle of elegant women and described the love affairs, rivalries, and painful separations that they experienced. Lesbos is an island off the west coast of Turkey, and its beauty influenced her verses.

She used phrases that expressed the charm of her world, including “juicier than a melon” and “balder than the clear sky.” She advised a friend to wear wreathes by saying, “Crown your hair with lovely garlands, Dica. Link shoots of anise with your lovely hands. The blessed Graces are drawn to wherever flowers abound.” The above photo of Aphrodisias, in Turkey, shows how pleasingly flowers and Greco-Roman architecture can blend.

Alcman was a Spartan poet who was probably active in the late seventh century BCE. His city had not yet developed the stern militaristic way of life that it’s now famous for. It was prosperous when he lived, and he mentioned many concrete particulars, including flower-like jewelry, porridges, cheeses (he also loved food), sleeping mountains, black earth, ambrosial night, tables, and yellow hair.

So as Greek literature began to expand from sublime Homeric portrayals of heroes and gods, it often focused on the commonplace within urbanized environments and portrayed them with vivid imagery. Rather than extending into vast metaphysical realms as Vedic literature often did, it developed even more ways to portray the here and now and did so in everyday settings. This trend befitted life in close-knit towns. Communal living in them was so engaging that poets lingered over ever more details in them.

They often did so while describing personal experiences and relationships with other people. Ancient Greek cities were conducive to highlighting concrete particulars, and this made them all the more engaging (Priene’s theater, where audience members could see each other as clearly as the stage, is shown above).

Above is Priene’s temple of Athena. In many ancient Greek cities, proportioned forms contrasted with uncontrolled nature, making urban life even more appealing.

Constant competitions made ancient Greek city life even more engaging. Contests were frequent in the annual cycle of religious rituals. People in all classes were continuously watching and interacting with each other.

People in all social classes don’t seem to have engaged with each other as much in ancient Indian cities. Several towns did grow large and prosperous. Jatakas (stories of previous lives of the Buddha, which were mainly written from the third century BCE through the fourth century CE) mentioned goods that certain cities were famous for. Silk, fine muslin, and sandalwood came from Varanasi; Gandhara was famous for red blankets; and Kashi and Madurai were honored for fine cotton textiles. According to the historian Upinder Singh, the number of trade guilds increased during this period, and Jatakas mentioned 18 of them. But Indian cities didn’t have Greece’s many public venues in which all citizens could share ideas and discuss politics. The Arthashastra described the ideal city, which had separate sections for each caste and no large theater, gymnasium, academy, or agora where all residents could come together and have common experience.

The Maduraikkanchi, a Tamil poem written by the fourth century CE, praises Madurai’s beauty and prosperity. But it mainly describes temples, religious rituals, markets, tall mansions, the king’s administration, and bustling streets with rivers of people speaking different languages. Public buildings from Greek and Roman cities, in which people in all classes could share ideas and decide on public policy, were lacking. Kautilya, in the Arthashastra, partitioned the ideal city into sections for the four main castes.

Commonly shared public life and proportioned spaces in ancient Greek cities influenced ideas that the earliest known Western philosophers emphasized. Many types of experiences converged in them, including law, sports, and theater. All these experiences reinforced assumptions that distinct entities that are proportioned with each other and linear relationships between them are the most basic reality, while Indians, Chinese, Africans, Middle Easterners, and Southeast Asians have usually thought in other ways.