Theater was yet another type of experience that reinforced ancient Greeks’ views of the world. It converged with many other experiences, including law, agriculture, the natural environment, and several others which we’ll soon explore to create the most common Western assumptions about reality.

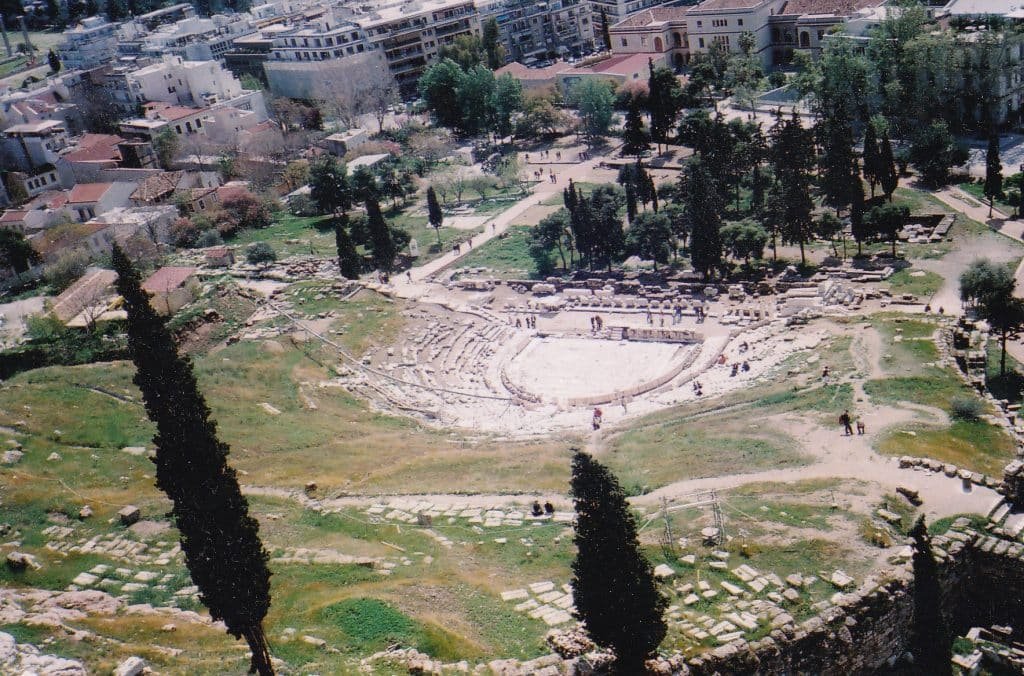

Athenians attended plays in the Theater of Dionysos, which climbed up the bottom of the acropolis on its opposite side from the agora. It was an open semicircle, like most ancient Greek theaters by the fourth century BCE. Some theaters before then were oval, including the one in the Athenian provincial community Thorikos. Instead of sitting in a hall and facing the same direction as people today do, spectators faced each other.

Like hanging out in the agora, watching a play was an intensely public experience to a degree that’s hard to imagine today. People could see the actors and each other’s reactions at the same time. Audience members could thus share emotions more deeply. A tragedy about the Persians sacking Miletus and enslaving its people made so many spectators weep that the play was banned and the writer fined.

In 458 BCE, Aeschylus produced his trilogy The Oresteia. In the first play, Agamemnon, the leader of the Greek warriors (Agamemnon) had just returned home from the Trojan War. His wife, Clytemnestra, bore a grudge because he had sacrificed their daughter to the goddess Artemis when storms prevented his fleet from sailing to Troy. Clytemnestra then teamed up with his enemy Aegisthus and killed Agamemnon in his bath (remains of the palace at Mycenae that he was presumed to rule from are shown below; this is only conjectural but the idea has sparked many imaginations).

In the second play, The Libation Bearers, Agamemnon’s son, Orestes, followed advice from the oracle at Delphi and took revenge by murdering his mother and Aegisthus. The trilogy’s last play, The Eumenides, began with another ghastly scene. Hideous winged female creatures called Furies chased Orestes to Delphi, where he asked Apollo for protection from them. But their wrath was hard to escape. They represented maternal bonds and feminine powers, and to them, matricide was the worst crime. They had no intention of letting the young man go.

Poor Orestes had inherited a family curse that began with his great grandfather Pelops’ chariot race with King Oinomaos of Pisa, which was a town or district in the Peloponnese, not the city in Italy. Every visiting male wanted to marry the king’s daughter, Hippodameia. Fanatically possessive, Oinomaos challenged each to a chariot race, won every time, and killed the suitor. Pelops, a wandering adventurer, visited Pisa, and Hippodameia immediately fell in love with him. She persuaded her father’s charioteer, Myrtilos, to sabotage his vehicle by replacing its metal linchpins with wax pins. During the race, they melted in the midday sun, the chariot fell apart, and Oinomaos was mangled to death. Myrtilos was in love with Hippodameia and made advances towards her. Pelops threw him into the sea, but before drowning he cursed the house of his slayer.

Pelops’s sons, Atreus (Agamemnon’s father) and Thyestes, created the ultimate dysfunctional family. They constantly competed as boys, but their rivalry turned to hatred when Atreus found that his wife and Thyestes were plotting against him. He invited Thyestes and two of his sons (a single son in some versions of the story) to dinner, secretly murdered the boys, had slaves place their heads, hands, and feet in a dessert bowl, and served it to their father. When a slave removed the cover, Thyestes realized that he had been eating the cooked flesh of his own sons as the main course. He bolted from the palace and never returned. But he had one surviving son, Aegisthus, who avenged his brothers by sleeping with Agamemnon’s wife when he was fighting at Troy and then joining her to murder him when he returned. This chain of horrible events was now passing to Orestes and perhaps into the indefinite future of this once great family.

But Aeschylus didn’t see this situation as karmic bonds that one could only escape by leaving society for the wilderness and meditating, as some Indians did when Aeschylus lived. Instead, Apollo defended Orestes in Athens’s homicide court, saying, “These old hags have no business tormenting this poor young man who was only repaying a horrendous crime.” The Furies countered, “We will never forgive him! Bonds with Mother are the most sacred!” The court’s votes were tied, so Athena cast the deciding vote. To appease the Furies, she granted them a place on the acropolis so they could be a positive force for vigilance in the city. Orestes regained his freedom and the Furies were guaranteed eternal respect. So the most atrocious crimes and curses were resolved in the heart of the civic community.

Instead of looking to a class of Vedic priests or a Babylonian or Egyptian monarch, Athenians solved problems in their own law court.

And this play was viewed in an open theater with the citizens in sight of each other. The scenes that audiences watched and their ways of viewing them mirrored each other.

Comedies were also more intensely communal than they typically are today. The type that people enjoyed when they were building the Parthenon and Socrates was inspiring young Plato often lampooned specific individuals with a battering ram’s bluntness. A person in the audience needed a robust sense of humor as his fellow citizens pointed at him and guffawed. Socrates is supposed to have stood up during a play by Aristophanes which made fun of him so that others could see him more easily. An authority-mongering fellow named Cleon charged Aristophanes with impiety for making fun of his enthusiasm for war in a play called The Babylonians, which he wrote while still in his teens. The old spoilsport couldn’t make the charge stick, and Aristophanes went on to enjoy a long career as Athens’s foremost comedic playwright.

Aristophanes’ language contained many blatant sexual references. Some historians have thought that this had roots in archaic rituals that were supposed to increase the soil’s fertility. People conducted processional dances and shouted obscenities and insults at each other as though the heated language would magically stimulate crop growth. If this was a root of ancient comedy, Athenians brought the tradition into their urban setting by holding it in their theater and using it to neutralize political extremists, deflate pompous windbags, and bring airy thinkers back to earth.

Today only the ruined semicircle remains in Athens, but it once roared with laughter and gleeful shouts. All this immersive communal bonding happened just 200 feet below the Parthenon.

The human scale of this combination of community and divine order must have been engrossing enough to make it seem unnecessary to look to vaster domains for meaning, as in Sanskrit theater.

Chinese theater also had unique roots, including Buddhist festivals in the Song Dynasty and city god temples (below).

The Greek world was different by enabling all of a city-state’s citizens to sit in view of each other, watch characters on stage debate and work through life’s most challenging issues, and feel the same emotions. All were in an open field, as agoras and athletic stadiums were. These types of venues converged into a common way of seeing, in which distinct entities interacted and were in clear view to all. The field they exist in is proportioned and within the human scale, so it’s possible to apprehend it rationally.

The semicircular theater became a common tradition in the Greek world by the third century BCE, including Delphi (below). Though it was a mystical place, people often experienced it within the same full view of each other as though they were members of the same civic community.

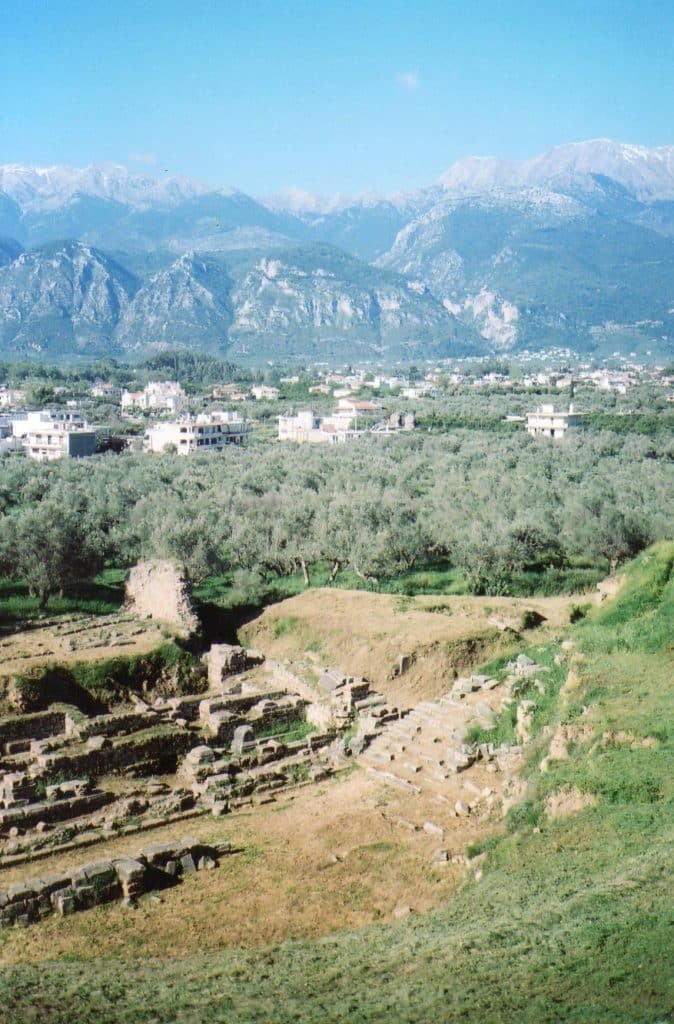

A theater was even built at Sparta by Roman times (below).

All the theaters, agoras, and athletic fields converged with other experiences to give Greeks a shared view of the world, which many historians have seen as the backbone of Western culture. We’ll explore other experiences soon.