Recent articles here have explored Western culture in the 13th century, when the great Gothic cathedrals were built. What was happening in Khmer society at the same time?

The historian Claude Jacques called the Bayon one of the world’s most mysterious and powerful religious buildings. It was begun around 1200, in the middle of the Khmer capital, Angkor Thom. Studying it brings you into the Khmer world during its zenith, and it reveals fascinating changes that had happened since Angkor Wat was finished about 50 years before.

King Jayavarman VII built it as his royal cult center after he began constructing the two huge monasteries/universities nearby, Ta Prohm and Preah Khan. The Bayon rises in the middle of Angkor Thom, and it was supposed to be the center of the Khmer universe. Ta Prohm and Preah Khan spread just outside the city walls. So the Bayon was the Khmer Empire’s centerpiece.

Some Khmer studies specialists have felt that the three great complexes were symbolically related. Ta Prohm was associated with Jayavarman’s mother and Prajnaparamita (a Mahayana Buddhist deity of wisdom). Preah Khan embodied his father and Lokesvara (a deity of compassion). The Bayon represented the Buddha and Jayavarman. David Chandler, one of the most distinguished historians of Cambodia, wondered if all three temples were thus related–wisdom/mother and compassion/dad gave birth to the Buddha/Jayavarman VII, who puts the whole universe in order.

Chandler was only speculating, but these buildings were probably symbolically related in some way, since they’re so big and close, and the same person built them. And the Bayon was seen as Angkor’s center. So Khmers probably conceived of it in relation to the other great monuments.

The word Bayon means ancestor yantra–a yantra is a complex symmetrical blend of shapes that represents the emanation of energies that the universe came from and their differentiation into its different worlds. The Bayon has an outer enclosure that once housed statues of dozens of elites’ ancestors and gods.

So the Bayon didn’t just house the Buddha and the king. It blended Jayavarman’s Buddhism with traditional Khmer ancestor veneration. The Bayon is a who’s who in the Khmer universe.

It’s thus no surprise that the entrance is regal.

The steps elevate you to the outer enclosure, which offers a dramatic view of the monument. The central spire was once about 150 feet high before it collapsed.

On the other side, an entrance hall has several carvings of dancing women. Dances were probably regularly conducted in Khmer temples. The Bayon and several other temples that Javavarman VII built have a hall that is on the eastern side of the complex’s entrance. Ritualized performances likely took place there (you can learn more about dance in ancient Khmer society the article on Angkor boogie).

But we’re only in the Bayon’s outer area. A journey towards its center takes you through a multi-leveled world that’s so rich that it left me speechless. The next enclosure is covered with sculptures of gods, people, and battles, as an enclosure in Angkor Wat is. But the Bayon’s friezes approach a revolution in perspective.

It includes the rest of us. Angkor Wat’s sculpture focuses on gods and the king, and the style of most is formal. The Bayon does have its share of soldiers as the former great temple does–Khmers still loved their action scenes. These images include a sea battle which might have represented troops driving the invading Cham soldiers from southern Vietnam out of Angkor–other interpretations have been proposed though.

Many Bayon fans enjoy its sculpture because much of it shows real people. Angkor Wat’s friezes mostly depict the king, nobles, gods and characters from Indian mythology. The Bayon shows ordinary folks.

Many of the Bayon’s scenes are true to life in Cambodia today.

The carvings aren’t as refined as most of Angkor Wat’s, but they’re more folksy–you can relate to the people across the centuries, like this boy walking behind the cart wheel of his parents.

You can peer into the lives of the folks who lived among the rice fields between the great Khmer monuments we admire today.

Not everything in these lives is pretty. The guys above have laid bets on a cock fight. They intently watch just seconds before the birds tear into each other. Sadly, this tradition is still alive in much of Southeast Asia. In communal societies in which people are expected to avoid shows of anger, cock fights enable men to let off steam.

But we can see a love of nature in the above shot. Monkeys sit in the branches, and birds fly overhead. All life-forms seem integrated within a dense tropical landscape, as they often are in Indian sculpture.

The people who carved the friezes on the Bayon were thus giving a full vision of life. Khmers often did–other great temples, like Banteay Srei and Angkor Wat, have friezes with these sweeping perspectives that encompass everything under the sun and beyond.

Many locals still worship in Angkor Thom’s Bayon. Hang out there for a while and you can meet a lot of great people.

But you can also linger over its sculpture and get close-up views of the lives of the ancient Khmers which you won’t be able to find anywhere else.

Many of the scenes are domestic and intimate, like this one of people eating under a pavilion or in an upper-class home.

Above, someone is either getting a delousing or a head massage.

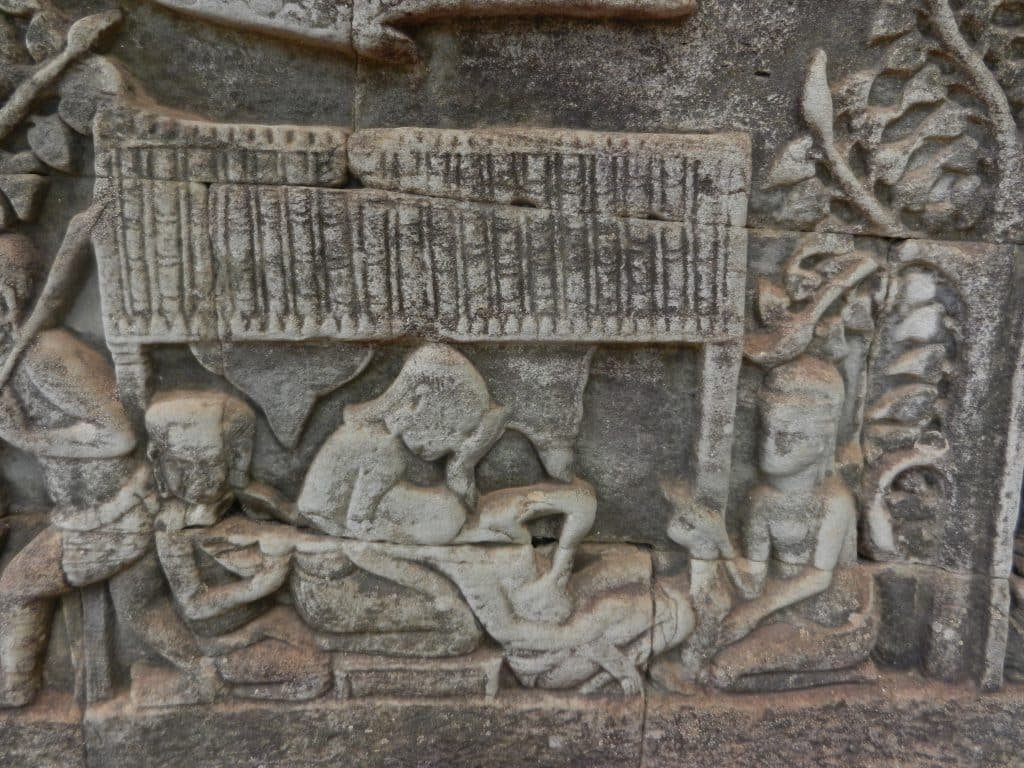

Other scenes on the Bayon also have medicinal themes, like this one of a woman in labor. Khmers put a lot of drama into their sculpture–at Banteay Srei, and Angkor Wat, and many other temples. The above Bayon scene shows the mother as contorted as warriors in battle. Two reposed women frame her and give her comfort.

The above scene takes us into the business world. Women weigh goods, and two Chinese men make comments. The Khmer economy was based on rice and and mainly domestic, since it lacked coins. But Chinese were increasingly arriving in the 13th century to trade.

The guys in the above shot want more visceral entertainment. Khmers staged elephant and boar fights in front of Angkor’s royal palace.

The men above are doing something more peaceful: worshiping.

These folks are preparing a feast. The Bayon has many scenes that are festive.

The people above are probably making rice cakes.

Khmers enjoyed circuses. Graceful acrobats and–

–brawny wrestlers provided a full range of entertainments.

But the Bayon was the main royal cult temple for the Khmer Empire’s most prolific builder, King Jayavarman VII. The builder of Angkor Wat didn’t portray many commoners on his cult temple. Why this change?

Crocks juice up Angkor Wat’s sculpture too. But the Bayon showed many scenes of ordinary people, so now the beasts feast on them as heartily as folks eating animals in their own feasts. What’s going on?

The Bayon was built in a crucial time. King Jayavarman VII erected it as his royal cult temple, but he took the throne after succession crises that followed the reign of Angkor Wat’s builder, Suryavarman II, and after wars with the Cham in Vietnam (a great and little-known culture well worth exploring). They invaded the eastern part of the Khmer Empire and possible Angkor.

Cham oarsmen in the boat in the above shot look determined to take their warriors into the heat of battle.

BP Groslier thought that the Bayon’s sculpture celebrates a great naval battle on Tonle Sap (the lake by Angkor, which floods the rice fields in late spring/early summer) in which Jayavarman bested the Cham warriors and drove them out of Angkor.

Khmer warriors are shown with close-cropped hair, elongated pierced earlobes, and a rope around their necks.

Khmer elites proudly rode with parasols, as they did on Angkor Wat.

The soldiers in the above shot might be Chinese. They have long beards, normal ears, almond-shaped eyes, and hair in topknots–they’re sharply distinguished from the Khmers.

Above, we can see Khmer and Cham warriors going at it.

But some historians, including Vittorio Roveda and Michael Vickery, have thought that there’s no convincing evidence for a great naval battle with the Cham. Some inscriptions say that the Cham came by land in carts. Roveda thinks that these Bayon scenes are of a mock battle that the Khmers staged during a festival which commemorated the Khmer victory.

The social scene on the Bayon is more complex than good Khmer/bad Cham. Both sometimes fight together in the same army as though Khmer and Cham soldiers split into different factions. The Bayon’s fight scenes might represent a series of many battles over a long period in which Jayavarman VII campaigned for the Khmer throne.

But whether “The Battle of Tonle Sap” was real or not, the military scenes enliven several places on the outer gallery that surrounds the Bayon’s central section. They alternate with scenes of daily life in Angkor. The latter have been admired for their folksy and sensitive portrayals of common people. The historian David Chandler noted that Jayavarman VII had embraced a form of Buddhism that stressed compassion. But if these ordinary scenes exemplify care for his people, why alternate them with so much violence, especially if it was just a mock battle?

Since Jayavarman had to assume kingship violently, he might have been demonstrating that the Khmer people’s well-being depended on his power to defeat their foes.

Tenderness and violence alternate many times on the Bayon. But all the scenes pulsate with energy. They don’t show people as distinct figures like Western sculpture often does. People are often animated and they interweave with dense natural landscapes, which include crocs with attitudes. Javayarman VII seems to have been showing himself as the hub of the universe’s order, which includes great battles and humble domestic life.

But we have only seen the outer enclosures so far. Why call the Bayon one of the most mysterious and powerful religious buildings ever constructed? We’ll find out when we explore its inner areas in the next article.