Several ideas that dominated modern Western thought emerged during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, such as:

- Nature is fundamentally composed of distinct objects.

- Objects move within three-dimensional space.

- Physical laws about objects and their elements are the ultimate things to understand.

- The self is separate from what it observes.

Though their dominance didn’t mature until the mid-nineteenth century, they were expressed with increasing frequency and coherence by the late seventeenth (when Newton and Locke were gaining followings that saw their philosophies as more mechanistic than they had intended), and these expressions became foundations for the later focus on them.

People in the Middle Ages lived with several other ideas that put all of nature in a unified framework. The first was God. They often saw all things as figures of His creative power. They didn’t see things as distinct objects as much as ancient and modern Westerners did. Instead, each thing had its place in a great chain of being–in a hierarchy of types of beings from the different classes of angels, to human beings, to different types of animals, to all the different insects and plants, and down to demons below. Everything was conceptualized in its place in a system with God overseeing all of it. The mosaics in Rome’s Santa Maria Maggiore (pictured below) show some of the higher levels in this hierarchy. Their stateliness reinforced assumptions that this hierarchy does not change.

Most people lived in simple surroundings that didn’t significantly change over the years. They went to the same barn every day, like this one in Regensburg, Germany.

This made it easier for them to assume that they lived in one universal hierarchy. Many resided within site of the castle or cathedral, as in Villeneuve, France (below).

The second idea was Jesus. People saw him as the central figure in history and as the savior of humanity. They saw history as a linear progression of ages from Genesis to the Last Judgment, and they often interpreted events in terms of this progression. The central events in history were the birth, death, and resurrection of Jesus for the salvation of believers. He was thus a central figure in people’s ideas of time.

Many ideas thus pointed to Jesus. Time did too. Some people thought that he was born 5,228 years after the birth of Adam. Others argued that it was 5,900 years, and others thought it was 6,000 years. But all these opinions shared the view of a universe that was unified by a temporal framework that was in human dimensions, with Jesus in the center. Below, in a Romanesque church across the Rhine from Bonn, he’s shown as the pivotal figure in history.

The third idea was the Church as Christ’s representative political body on Earth. The local parish made this idea concrete in every city and town. The church was a community’s focal point. Its spire made it the tallest building in town. Most people were illiterate, and the local church was their text. Inside, people marveled at images of Jesus, saints, biblical stories, and the structure of the universe. The church’s architecture and art taught people about an integrated universe under God and Jesus. Cathedrals portrayed the whole cosmos. The seven days of creation, the prophets, the life of Jesus, the twelve apostles, the heavens above with the nine types of angels, and the underworld with hideous gargoyles and demons baring their fangs were all encased in stone (and then in gloriously shining glass in the new Gothic cathedrals), in an integrated framework under God, who created it all.

Everything had its place in the Great Chain of Being and in systems of symbolic meanings that were figures of divinity. Thus the straightness of a sword was a figure of the straightness of faith. The redness of a rose symbolized the blood of martyrs and the charity of Mary. A white rose symbolized her chastity. A road symbolized the quest for spiritual salvation. The sea symbolized the world and its temptations. A bunch of grapes symbolized Jesus, who gave his blood for mankind.

Numbers also had symbolic meanings. Three symbolized the Trinity. Seven was central in many categorical schemes. The twelfth century English polymath John of Salisbury wrote a book called De Septem Septenis, which outlined many groups of sevens, including the seven types of erudition, the seven liberal arts, the seven gifts of the Holy Spirit, and the seven degrees of contemplation. Human life was divided into seven ages, and each age was associated with one of the seven virtues. The seven sacraments sustain people in the practice of these virtues and keep them from committing the seven deadly sins. Things and numbers thus fit into a tidy system within the universe that God created.

All these ideas and images of an integrated universe with everything in its place under God were central in people’s lives. We can imagine a farmer in the 13th century (more than 80 percent of the people in Europe were farmers then) standing in the fields. In every direction, he saw signs that nature is unified. He could look down and see the growing crops as figures of God’s creative power. He could gaze ahead at the ox pulling his plough and see a figure of the evangelist Luke (each of the four evangelists of the New Testament was symbolized by an animal) and of strength and steadfastness. He could also think of God’s declaration in Genesis that humanity will dominate all beasts. He could look up and see the brilliant sun or brooding clouds, or hear the rustling wind, and feel a greater sense of God’s creative power. He could look at the tower of the parish church or the lord’s castle and see symbols of social order, which he would have considered rooted in the divine order. For example, Wells Cathedral (below) was the center of perspective for people who lived in that town in the 13th century.

A farmer could look forwards or backwards in time, and the same saints’ festivals were there year after year. Time was not as much of the abstract line that dominated modern society. The calendar was full of events with religious meaning. Some days represented saints, and the hours of the day were associated with religious services, such as the evening hours of Vespers. The chiming of the local church bells told the community that Vespers was beginning. Time was often seen as unified, and its main divisions had symbolic meanings that could make people feel connected with the whole universe.

So, many ideas reinforced the assumption that the universe is integrated and rooted in God. Everything had its place. Every class of angel, every major character in the Bible, and every life form on Earth was conceptualized in a great chain of being within this integrated universe. Angels above, beasts below, humanity in the center. Every being and every event was meaningful.

By the 16th century, people had lost consensus about medieval ideas that integrated the cosmos. The fundamental principles of nature and thought began to shift to ideas that focused on separate objects because they could be more solidly grasped. The separate object and its dimensions, mass, and forces that move it within three-dimensional space gradually became intellectual centers of gravity. Several experiences converged to encourage this change.

People saw a lot more novelty in the sixteenth century. There were more types of objects that they had to comprehend. Most people in the Middle Ages owned few things, so it was easy to place them into the the Great Chain of Being’s system of meanings. Even people wealthy enough to own formal gardens, like the one in Strasbourg (below), thought each plant had symbolic meanings.

But explorers were now discovering and bringing back to Europe plants, animals, and people that Westerners had never seen before. There was an influx of new types of objects, and people lacked consensus about how to classify them, including this beautiful insect I found in front of my guesthouse in Laos.

The Great Chain was now so crowded that it was becoming too unwieldy to organize all knowledge.

The recognition of more types of objects helped overload the medieval systems of correspondences and symbolic meanings. Though the Great Chain was still one of the most dominant concepts in the eighteenth century, people were beginning to drop the symbolic meanings of things. The sixteenth century French humanist Francois Rabelais made fun of the symbolic meanings that people in the Middle Ages saw in colors. White does not stand for faith; blue does not symbolize purity; they’re just colors. He asked readers what was pricking them into thinking such silly things.

A. Richard Turner, in Renaissance Florence, wrote that three-dimensional perspective didn’t become the West’s dominant framework for reality overnight. People in the 16th century also still believed in astrology, prophecy, and magic. Locals acting as prophets shared Florence’s streets with the bankers and merchants, and one of that city’s most eminent 15th century intellectuals, Pico della Mirandola, believed in the efficacy of magic. People throughout Europe in the 16th century also believed in witchcraft, demonology, and numerology. Florence’s crowded neighborhoods (below) were diverse places with many ways to interpret meanings.

But three-dimensional perspective slowly kept penetrating Western culture, and it did so in new ways. Europeans in the 16th and 17th centuries found it useful as their states expanded and competed with each other. Mapmaking became more advanced in the 16th century, and every major city was drawn so that people could follow its streets and see each building. John Hale, in The Civilization of Europe in the Renaissance, said that cartography was almost a craze then. Europe’s population grew, literacy increased, governmental bureaucracies expanded, and the largest states began to colonize other continents. The new perspective helped people manage growing amounts of information by allowing things to be more precisely located. The new printing industry allowed maps to be produced and circulated widely.

Globe making grew at the same time. People who could afford one could see all the world’s major landmasses and political states reduced to a three-dimensional grid. Nuremberg (below) was Europe’s leading place in globe making at the beginning of the 16th century. Merchants owned many of those tall houses, and they were keen on tracking events in different places. The great painter Albrecht Dürer owned that house on the upper left of that tree in the lower right, and he was also keen on learning about the physical world.

Fernand Braudel, in The Perspective of the World, wrote that the West’s economy was becoming more integrated in the 16th century, mingling currencies and goods as trade across borders and between continents increased. Lisa Jardine, in Worldly Goods; A New History of the Renaissance, said that books for recording profits and losses and maps of the world which detailed shipping routes and trading relationships were closely associated in that century. The world was becoming more unified by the market as battles between medieval Catholic traditions and new Protestant faiths were shattering people’s dreams of Christian unity, and maps helped to bring unity and order to this new world of more trade and less shared faith.

The Fugger family in Augsburg, Germany played a key role in spreading the importance of finance as their bank financed projects all over Europe. Other wealthy families built these homes across the street from the Fuggers, demonstrating the market-based economy’s rewards.

Antwerp (below) then became the West’s financial center in the mid-sixteenth century.

As trade increased, people proudly commissioned artists to display their belongings. Painters used their new mastery of realism to show their patrons’ glittering jewelry, sparkling coins, glinting mirrors, luscious fabrics, sturdy horses, palatial homes, ornate furniture, and expansive gardens.

At the same time, landscape painting was becoming an independent genre. From the towering Alps to the flat farmlands around Dutch and Flemish towns, all the natural environments that Europeans knew were increasingly portrayed in three dimensions. More human-made objects and natural landscapes were being depicted in ways that allowed people to analyze, control, and display them.

Scientists increasingly focused on analyzing objects. In Thinking with Objects; The Transformation of Mechanics in the Seventeenth Century, Domenico Bertoloni Meli detailed how objects, including levers, beams, pendulums, springs, and falling bodies were given center stage in the study of mechanics. Brache, Kepler, and Galileo treated planets as bodies that obey the same mechanical laws that objects on earth do. This debunked older medieval ideas that Heaven is a spiritual realm that’s different from the physical world we live in.

Copernicus, Brache, Kepler, and Galileo discredited other medieval ideas of the cosmos. People formerly believed that the earth is the center of the universe. This idea implied that human affairs are central in God’s plan. Now that scientists were debunking this idea by finding that the earth revolves around the sun, the world seemed more uncertain and lonely. We might not be Daddy’s favorites after all. The historians Jacques Barzun and Richard Tarnas noted that the new heliocentric perspective boosted confidence in human reason, but it also created uncertainty about who and where we are in the universe.

Galileo looked into the heavens with the newly invented telescope and found sunspots and more moons and stars than anyone had seen before. He added around 80 stars to Orion’s belt. This meant that there were more things in Heaven as well as on Earth. Imagine the surprise the Dutch inventor Antony van Leeuwenhoek must have felt when he put a drop of water under a microscope and saw tiny amoeba swimming around. Where did these creatures fit in the Great Chain of Being? The newly invented telescope and microscope were revealing many types of things that nobody had previously seen.

In the 17th century three-dimensional perspective and modern science helped each other to develop into ways to comprehend all these newly discovered objects. The coordinates of the X, Y, and Z axes, which today’s high school students learn in their first algebra class, began to be used then. Isaac Newton’s physics charted motions of objects by plotting the distance they traveled on one axis and the duration of their journeys on another, thereby allowing their future trajectories to be accurately predicted. The enormous diversity of new objects could now be unified by Newtonian mechanics.

Ideas of time began to mirror concepts of space. Clocks were installed on many town halls in Italy in the 15th century, and wealthy people began to use portable timekeepers by 1500.

Clocks had been used in monasteries and churches to signify the times to pray and hold masses, but people now began to partition time into abstract units and apply them to their daily lives in the material world as business in it became more complex. The expanding governmental bureaucracies increasingly recorded people’s births, marriages, and deaths, so it became more common for people to locate the most important events in their lives according the precise times and places in which they occurred. The new views of space and time were beginning to shape people’s identities.

Three-dimensional perspective grew in other ways, which were more tangible than abstract mathematics. Language was changing to reflect the emerging way of seeing. For example, people in late 17th century England were increasingly finding the verbiage of Shakespeare’s time (around 1600) excessive. They now wanted more precision and clarity and considered the earlier outpourings of words obscure and unwieldy. They used to be good fun. In Shakespeare’s Henry IV, Part I, the youthful prince is hanging out with a fat old wine-guzzling former knight named Falstaff, and both playfully insult each other. Henry calls his companion, “—this sanguine coward, this bed-presser, this horseback-breaker, this huge hill of flesh—.” Falstaff then makes fun of the skinny youth with this exuberant flood of words, “—‘sblood, you starveling, you eel-skin, you dried neat’s-tongue, you bull’s pizzle, you stockfish—o for breath to utter what is like thee!—you tailor’s yard, you sheath, you bowcase, you vile standing tuck!” A standing tuck was an upright rapier, and a bull’s pizzle was its penis. Falstaff’s tongue even outstretched his own girth. Below is a shot from London’s replica of the Globe Theatre, where audiences enjoyed such verbal liveliness.

But humor then became more subtle. In 1681 John Dryden lampooned the prolific womanizing of England’s current king, Charles II, by saying that he “Scattered his Maker’s image through the land.” Understatement in a few well-chosen words was replacing the broad caricatures from the beginning of the century, at least among the middle and upper classes who wanted to distinguish themselves from the unlettered.

In Dryden’s day the English language was moving away from the variety and license from Shakespeare’s time. The Royal Society was established to advance scientific inquiry, and its members wanted sentences to be short and clear. They should detail objects, their qualities, and their locations rather than encourage rhetorical flourishes.

This preference for clarity extended far beyond scientific circles. Newspapers were emerging at the beginning of the 18th century, and people wanted accurate accounts of what was going on around them.

Barbara J. Shapiro, in A Culture of Fact, wrote that desires for clear descriptions of details grew in several other fields around that time. As more people were trading and colonizing other lands, travel writing grew and readers wanted to know about other places in a truthful way. People also wanted more focus on facts in history writing and in courtrooms. The novel emerged as a popular literary form then, and readers wanted clear descriptions of characters, places, and events.

Languages changed to accommodate all these demands. In Shakespeare’s day people could use words more flexibly. Many were used in several parts of speech. Nouns could become verbs (“Grace me no grace nor uncle me no uncle” is from Shakespeare’s Richard II), and adjectives could also be used as verbs (a person could happy her friend). Verb forms were also flexible. People could choose between multiple forms of the present tense’s third-person singular, such as telleth and tells, and singeth and sings (the latter s ending spread from northern England as more people moved to London in the 16th century; people increasingly discarded the eth ending in the early and mid 17th century—it sounded more formal by then and was thus still sometimes used in serious writing). People could also choose between different forms of adjectives, such as famousest and most famous.

The flexibility of English in Shakespeare’s time made it a joy to speak. People could express themselves more spontaneously and exuberantly than predictably, so they deeply enjoyed bantering. But by the end of the 17th century, meanings of words and their functions in sentences needed to be stable so that things could be described and located in a world which was increasingly seen as a three-dimensional grid.

This happened in Italy too, where a dictionary was published to purify language with standardized word meanings. It was also taking place in France. Cardinal Richelieu established the Academie Francaise to give the French language rules to allow scientists to communicate with each other.

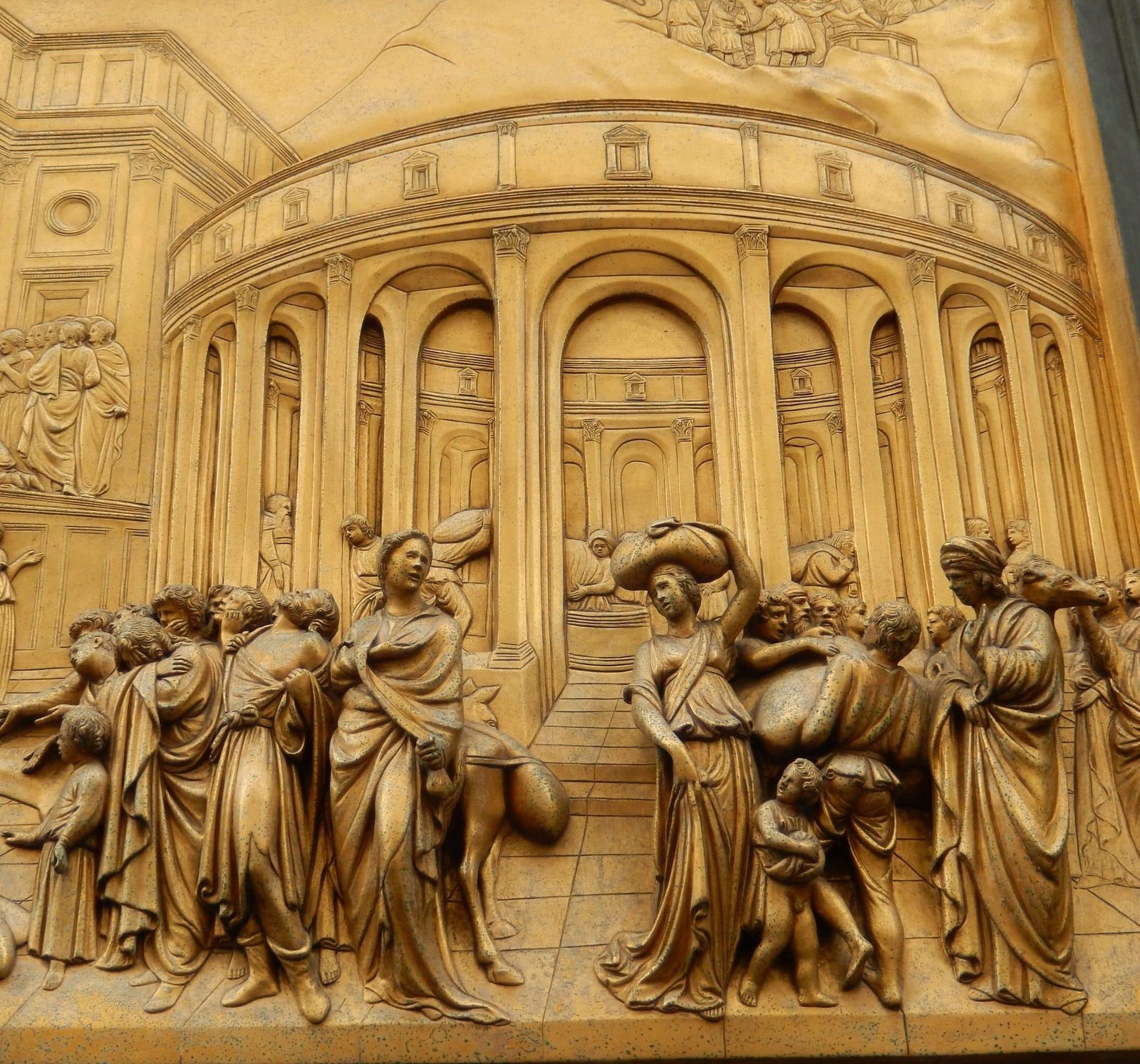

Three-dimensional grids became more prominent in cities so that the eye got the same models of reality that the ear did. Government buildings, upper class homes, and churches in London, Paris, Amsterdam, Vienna, and Prague were designed with colonnades, semicircular arches, and domes, and they became standards of success. The sober classical architecture of homes of some of the many wealthy merchants in 17th-century Amsterdam is shown below.

A fire wiped out the center of London in 1666. Though this was disastrous at first, people rebuilt their city with stately proportioned buildings, including St. Paul’s Cathedral. They provided visual standards as London grew into one of the world’s main centers of science, commerce, and enlightenment philosophy.

The 18th and 19th centuries saw more of nature and humanity conceived in terms of three-dimensional perspective. Latitudes and longitudes, amounts of force, economic supply and demand, changes of population, biological processes, and public opinions were increasingly plotted and analyzed on abstract two-and three-dimensional grids.

Paris’s Louvre gave me a revelation: Some currents that encouraged three-dimensional perspective even flowed into people’s stomachs. Its large selection of European ceramics showed a major change in images of well-being around the beginning of the 16th century. Before then much upper class tableware was painted in intricate geometric patterns that reminded me of Islamic designs. But after 1500 more plates, bowls, and drinking cups sported scenes from biblical narratives and ancient Greek myths, with life-like people in front of buildings with classical columns and porticos.

People didn’t only admire the new realism in the great artists’ works; they brought it into their homes and enjoyed it as they dined, celebrated weddings, and entertained business clients.

In innumerable daily interactions, people with money associated classical styles with good living and distinguished themselves from the lower classes who couldn’t afford these new fashions. Their appreciations of this type of art were emotional as much as intellectual—they associated it with security and well-being.

More and more currents thus kept emerging and reinforcing each other to make three-dimensional perspective and ideas of distinct objects dominant in the West. What seems obvious actually isn’t so . It comes from an infinitely abundant cultural landscape.

People in different cultures thus think about “objects” in a marvelous variety of ways. You can explore a way of thinking about objects that’s common in Southeast Asia and another variety in Africa.