Paris’s Notre Dame Cathedral is one of Europe’s most iconic buildings, and its creator planned it that way from the get go.

Here are some key facts about it:

1. It was begun in 1163 by Bishop Maurice-de-Sully. He was an incredible person. Sully was from a peasant family near the Loire River, and he trekked to Paris to study in the schools that were converging into the University of Paris. Universities were emerging in Europe’s growing towns, and young men with big ideas were gravitating to these newly urbanized places.

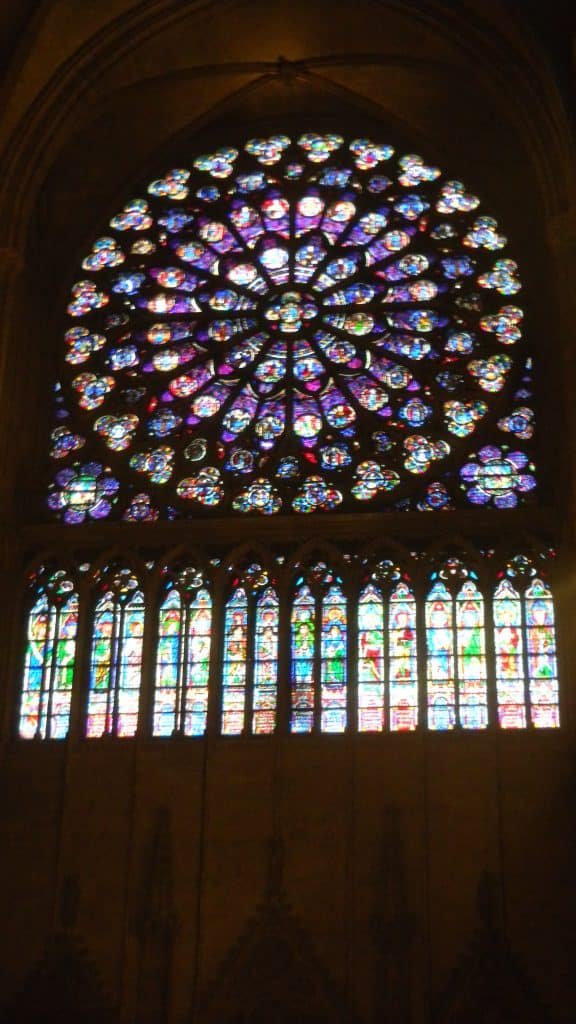

2. Paris’s Notre Dame’s interior is dark for a Gothic cathedral. Laon Cathedral was begun just a few years early, and it’s nave is so bright that you can think that divine light infuses it.

3. The first columns built in the nave are plain cylinders–they’re the closest to the choir (you can see them on the right in the above photo).

All these features created a stern atmosphere.

But Notre Dame Cathedral’s construction evolved over the decades. Gothic style developed more and the cathedral grew with it, transforming from a brawny demonstration of power into a great work of art and one of France’s most enduring monuments.

At first, its builders emphasized size, but over time, several things made it seem more spiritual and gentle:

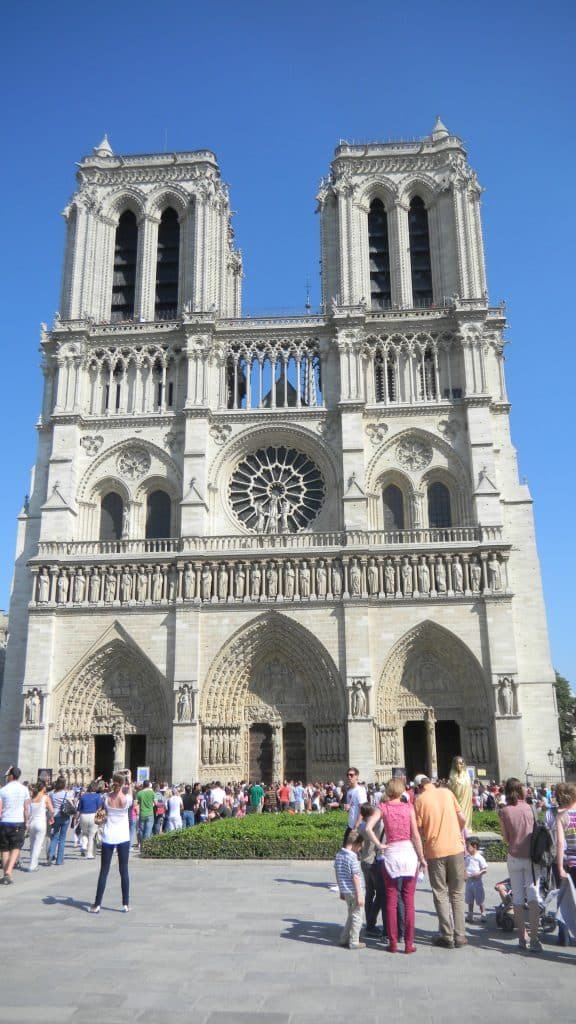

1. It’s the first monumental building with flying buttresses–many of the ones you see today (and in the above photo) are 19th century reconstructions. They were invented in the 1180’s. Before then, builders relied on thick walls and hidden buttresses. But Notre Dame’s master made the buttresses visible, and they became a major feature of the great Gothic cathedrals that followed, including Chartres. They changed the look of the nave from a hulking mass to a forest of arches and spires that seem to embody the soul’s rise to Heaven.

2. A new master came from Chartres and he finished the nave. Cathedrals were constructed from the eastern end, where the choir is. He began Notre Dame’s majestic west facade (its main entrance) around 1200.

3. France’s king from 1200 to 1223, Philip Augustus , led his army into Normandy in 1204 and captured the main stronghold of the English in France, Chateau Gaillard. The bulldog knights were now in retreat. Philip was bent on centralizing and building the monarchy. Paris Notre Dame Cathedral was becoming a perfect statement about the glory of France and its crown.

4. In 1220 the base of the west facade’s gallery of kings was finished. The French monarchy now had a place in God’s sacred order.

You can see some of its members presiding above the arches over the 3 entrances in the above shot.

5. In 1225 the rose window was finished, and the towers were completed in the 1240s.

6. With the towers, Notre Dame’s facade becomes a square and a half. It has a geometrical logic.

7. The facade’s vertical and horizontal features balance each other within this outer form. All features are logically related. Universities, which had emerged in cities in the 12th century, were teaching scholastic philosophy, which says that everything in the universe has its place in God’s order of things. So the sheer size which Notre Dame’s designer went for in 1160 became more sophisticated by the 1240s–it now reflected an urbane world of academics and merchants who were literate and analytical.

8. The square and a half which frames these interrelationships balances earthly dominion (the horizontal dimension) and sacredness (the vertical). Notre Dame doesn’t take flight like Chartres Cathedral or Amiens Cathedral seem to. It stands firmly on the earth. The fusion of royal power and sacredness seems like the permanent order of things.

9. At least it did in the Middle Ages. Notre Dame was vandalized in the French Revolution. Zealots cut the heads of statues of saints. The whole building was slated for destruction, and its stones were put up for auction. But the Revolution’s leaders finally decided that atheism was counter-revolutionary. They remembered the 18th century wit Voltaire’s quip, “If God didn’t exist, we would have to invent him.” Whether he exists or not, France’s past does, and it’s too glorious to destroy. Maybe its allure brought the extremists to their senses.

The first time I ever arrived in Paris, I walked from the Gare du Nord train station to the Seine River and entered the cathedral. A mass was about to begin and I found a seat in the front row, where I basked in light emanating from the stained glass windows in both transepts. The choir sang and a young woman with a beautiful voice led it. I then enjoyed the French language’s music when the priest lectured, and the aroma of incense blended with it. I was thinking, “What a wonderful fusion of senses to greet me when I first get to Paris!” when a roughly sixty-year-old woman two rows behind me interrupted my reverie.

She sat alone and began to loudly rant to no one in particular in a raspy tone that was full of anguish. She continued for several minutes without pausing, and this made me think that she had severe psychological problems. A middle-aged man sitting about six seats to my right finally turned around and pointed at her with a menacing expression. She quieted down for two or three minutes but flared up again. He then stood up, turned around, and was about to dart over to her.

An usher rushed over to him when he began to take the first step, put a hand on his shoulder, and said, “Monsieur!” His tone was equally firm and soft, as though he was saying, “Give a troubled soul a break.” This was Mother Mary’s house. Her cult had spread through Europe in the 12th century, when the construction of Notre Dame began, and many Gothic cathedrals were dedicated to her. It was as though she took the woman into her hands. After the savory mixture of perceptions, I witnessed her cult and house can make people more compassionate.

One of Paris’s most enduring buildings fuses lofty political and spiritual ideas with human gentleness. It also integrates heaven and earth. Bringing all domains together, it has been an enduring symbol of civilization for France and the rest of the world.