Chinese have traditionally seen themselves as rooted in the Shang Dynasty. So you can’t get more foundational than the Shang and its roots. We’ll get really foundational in this article with facts about a neighboring culture that preceded the Shang and inspired it, the Erlitou.

Chinese culture had already been developing before the Shang Dynasty. By 5000 BCE villages that farmed had grown along the Yellow River and the Yangtze. In the Yangshao period (5000-3000 BCE), communities on both rivers became interlinked and traded goods with each other. During the Longshan period, urban settlements began to grow. But Chinese culture’s momentum picked up during the Shang dynasty.

Ancient writings described a dynasty that existed just before the Shang called the Xia. The Shang is supposed to have conquered it. Archeologists discovered the Erlitou culture in the late 1950s, and many scholars have thought that it was the Xia capital.

The Erlitou culture flourished to the west of the Shang, in Shanxi and Henan. Its capital was a little east of modern Luoyang–both cultures consolidated large areas around the Yellow River.

The Erlitou developed a characteristically Chinese political structure, and the Shang and Zhou dynasties later adopted it–

Lu Liancheng and Yan Wenming, in The Formation of Chinese Civilization, wrote that a strict hierarchical lineage system evolved from existing clans. The Erlitou and Shang cultures unified themselves with a king, his lineage, and several ranks of elites. All shared kinship relations and worshiped common ancestors. So political power, familial relationships, religion and geography meshed in Chinese civilization’s early stages.

The ceramics in the two photos above reflect this network of ideas. The higher one is of several jue vessels, which held wine. The lower pic is of a ding, which held meat. Elites used both in ceremonies to honor ancestors. They were two of the most common forms that bronze makers were beginning to fashion.

Chinese thought has usually seen the world and universe as an integrated whole–the flows of yin/yang energies, which were later articulated in the first millennium BCE, are based on this vision. Cultures in Mesopotamia conceived of gods as more distinct from people. The ancient Hebrews, who emerged on its fringes, evolved to the idea of a single god who created and rules the universe with firm laws. But Chinese culture has emphasized a cosmos in which humanity, gods, spirits, and nature share the same patterns as though they’re a harmonious family.

Beijing’s Summer Palace (above) expresses this view of reality–water, plants, and buildings blend into one landscape, and a courtyard encompasses the whole perspective as a whole which includes both politics and nature. The Erlitou culture was already heading in this direction 4,000 years ago.

Emperor Yongle in China’s Ming Dynasty put up a great spread in the early 15th century. Beijing’s Forbidden City would make George Washington Vanderbilt’s mansion in Ashland look like a shack.

But Yongle was treading in footsteps that kings in the Erlitou culture took more than 3,000 years earlier.

Cities grew in the Yellow River’s central plain, where the Erlitou and Shang cultures ruled. K.C. Chang wrote that both dynasties had a permanent sacred capital and several secular capitals which moved over time.

The old capital housed the king’s ancestral temple. People conducted special ceremonies there with sacrifices. The elegant jue in the above shot was probably used to share wine with honored predecessors’ spirits and encourage their protection.

Lu Liancheng and Yan Wenming wrote that these cities weren’t created by a market economy. The royal family developed them as the centers which they ruled from.

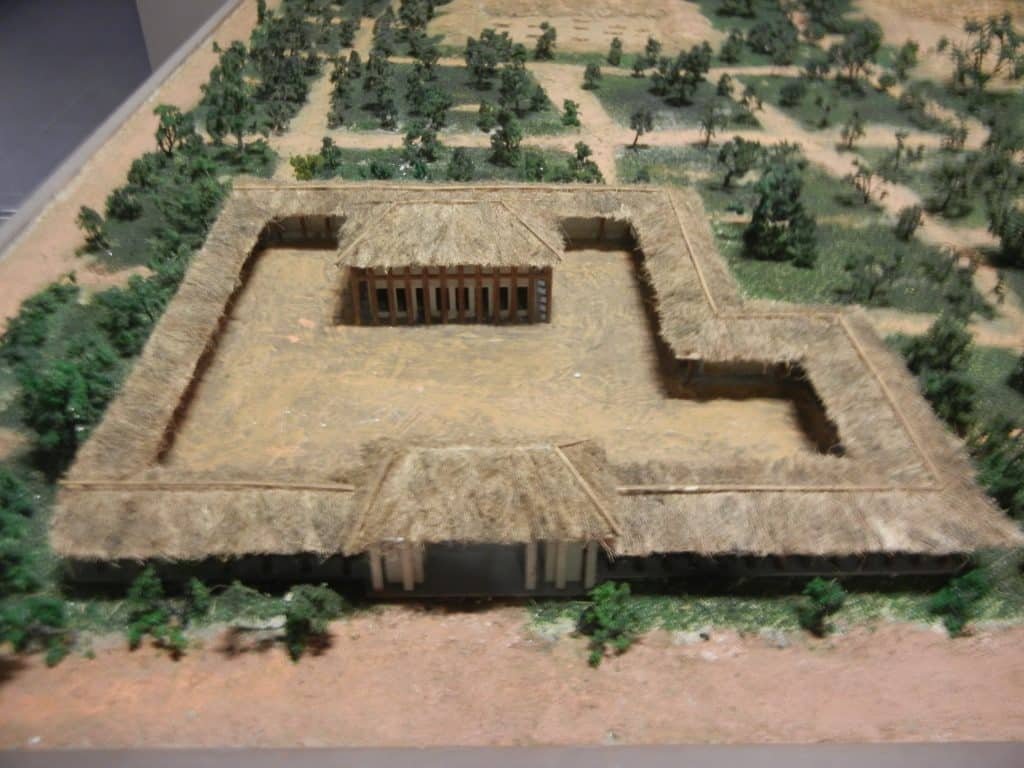

The above photo is of a replica of the Erlitou palace. The stately hall in a large courtyard was surrounded by a wall–the palaces of later dynasties took this form, including Beijing’s Forbidden City. So Yongle was walking in very ancient footsteps.

Cities in the ancient Greek world were centered on the agora–the open public area where people traded, settled legal disputes, and just hung out because it was where most of the town’s action was. But an artisan along the central Yellow River in 1500 BCE would have trekked to the palace. Politics, commerce, art, and ideas were more centralized in China.

Lu and Yan wrote that Shang cities had big differences in social rank and wide gaps between the rich and poor. Neighborhoods around palaces might have looked like the Yunnanese village in the above picture. The palace must have greatly stood out among clusters of undistinguished homes and walled compounds, projecting its authority throughout the realm.

Kings began to invest a lot in ways to maintain the social hierarchy. They made cultural patterns that emerged in the previous Yangshao and Longshan periods more sensational and entrenched them as standards throughout China.