Most archeologists and linguists believe that Thais originated in southern China. As their populations rose and as the Qin and Han Dynasties expanded into the Yangtze area in the last three centuries of the first millennia BCE, Thai groups (technically “Tai”–“Thai” refers to people in the modern country and its emigrants, while “Tai” is more general, referring to all Tai ethnic groups; I’ll keep it simple here and use “Thai” ) spread as far as northwestern Vietnam and northeastern India. So Thai cultures became very widespread.

There are still Thai-speaking groups in many countries outside Thailand. But this great culture isn’t usually taught in schools. One of the reasons is it’s hard to get a handle on. Its people thought in different ways than they have in better known civilizations like China and India. But Thai cultures encompass a wide area, are very creative, and still thrive. So we’ll venture into their ancient roots.

Ancient Thais unified their world in a different way than Chinese and Indians have. A key concept was muang. It has had so many meanings that the historian David Wyatt says that it’s hard to translate.

One of its meanings was in relation to the village, the ban. A muang referred to a larger territory which encompassed a cluster of villages. The bans within it formed a unit that pooled resources for common defense. The most important ban in the area acted as a hub for trading, defense, and rituals.

But the meaning of muang was personal as much as geographic. The head of the most important family in the central ban often acted as the headman, and he erected a pillar outside of his house which people treated as the axis of supernatural powers. He could distribute them throughout his territory with rituals. For his protection, people owed him tribute in the form of rice, handcrafts, and labor.

People still honor the city pillar in modern Thailand–Bangkok’s presides across from the Grand Palace, and many locals pay their respects, like the ones in the above photo.

People still conduct rituals there. The above musicians accompanied a dance performance.

So the term muang has referred to several things at the same time:

1. A hub village which was above the nearby ones in a hierarchy.

2. The area encompassing all villages with common rituals and defense.

3. The headman over all the villages.

4. The supernatural power of the land that the villages called home, including its power to generate life (such as rice growing) and the nature spirits and human ancestors that hung around it.

5. A safety zone which everyone under the headman’s protection shares. It’s traditionally distinguished from the surrounding forests and mountains, which are full of bandits, wild animals, and dangerous spirits.

The word muang doesn’t fit Western, Chinese, or Indian categories–it’s a key ancient Thai concept which has to be understood on its terms, but what a rich range of terms!

The world of the muang seems to have had many contraries. It was both intimate and full of nature’s awesome power. It was a unified territory, but pluralistic by being profuse with spirits and ancestors.

And muangs were flexible–people were relatively free to conduct their local affairs as long as they paid tribute and contributed their muscles if their was a war. They also moved to a different muang if its headman showed more power than their current one.

Thai domestic architecture made moves relatively easy. Stilt homes could be taken apart, moved, and reassembled.

Ancient China was different. From the Shang Dynasty on, a royal court centralized human life as the hub of economic exchange and of rituals. It also centralized the spirit world. But the Thai world was pluralistic, since many muangs coexisted, and they expanded and contracted as leaders’ power waxed and waned.

Ancient Greece was also different. The city-state was associated with a more permanent land area, a topos. The Greek world was partitioned into several distinct places whose identities remained stable as long as someone else didn’t invade it.

A lot of Thai art forms express this world, which is abundantly pluralistic on one hand and unified in a social hierarchy and embedded in the natural environment on the other. Bangkok’s Grand Palace (above and below) projects both an irreducible variety of forms and the royal family’s power to unify Thailand.

You can wander around the Grand Palace and never exhaust the blends of forms and colors, but the whole landscape is under the grace of the King and the Buddha.

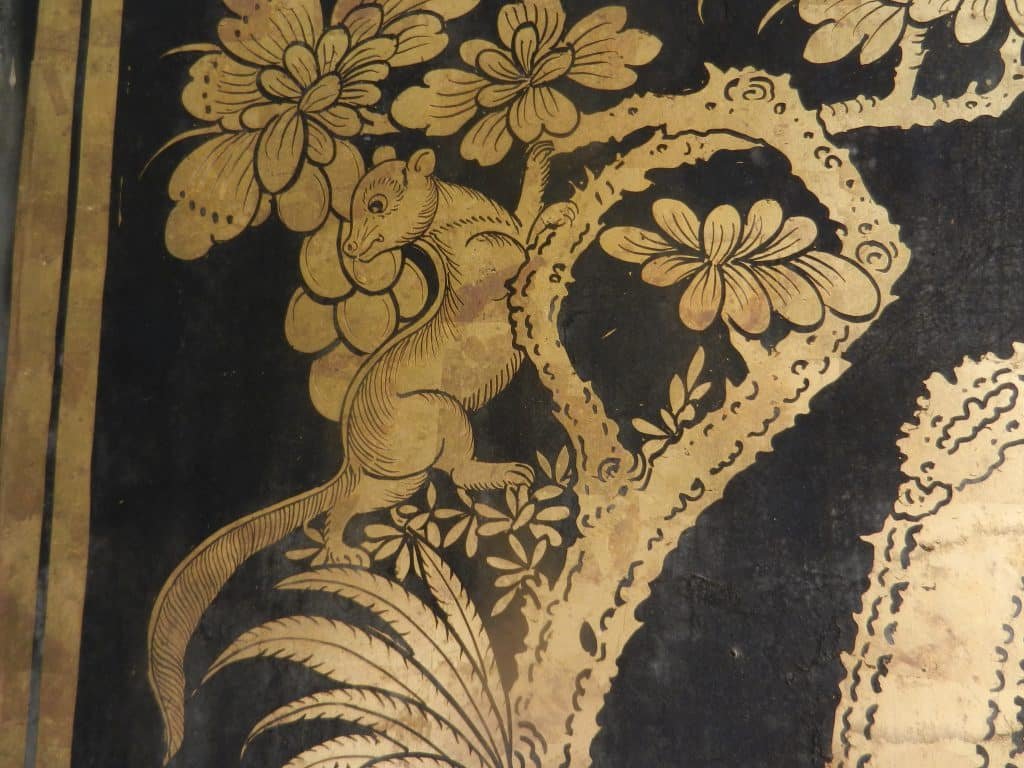

Many small-scale art forms in Thailand have the ancient muang’s combination of profuse energies and charming intimacy.

The critters in the two above scenes are great touches to a larger scene of a tree.

Nothing shows this blend better than the Buddha’s footprints at Wat Pho.

The term muang wouldn’t pass in a philosophic statement according to modern Westerners, because it has too many meanings to be nailed down. But it helped unify the worlds of ancient Thais living in small riverine valleys and in uplands from India to Vietnam, who have created some of the world’s most beautiful art. Its meanings still thrive and the world is richer for it.