Mosque architecture emerged in a dramatically different cultural environment than the West’s ancient temples and Christian churches. Things that seem simple have limitless depth there.

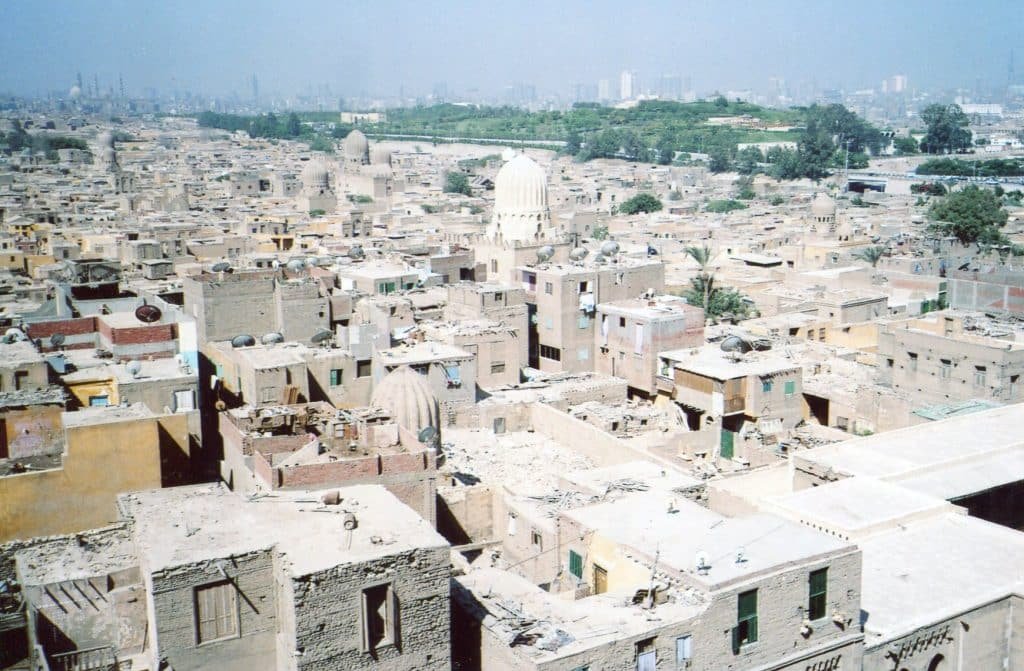

The skyline in the above photo is Cairo’s, which I took from the Ibn Tulun mosque’s minaret. We can enter this mysterious landscape and see a key way in which the Islamic world differs from the West.

As Europeans were building Gothic cathedrals in the 11th and 12th centuries, they increased the areas of stained glass windows and sculptural friezes, and they thus had more space to put biblical stories and personalities on. An explosion of humanistic art followed, and this reinforced the West’s orientation to pictorial art, which represents people and narratives.

But Islam was developing other ways of seeing the world, which are also very rich.

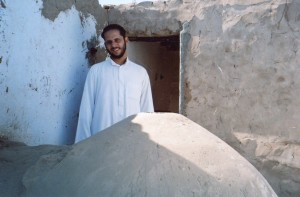

The mosque’s minaret is a key part of Islamic thought. Like the mosque’s courtyard and mihrab, the minaret expresses the follower’s direct relationship with God without the need for priests or pictures of saints.

The pictorial art of Gothic cathedrals couldn’t develop in mosques because representing humans and animals in mosques has been forbidden. So artistic energies in Egypt sometimes went into making the minaret more ornate. Many consist of a circular drum tower on top of an octagon, which rests on top of a square base. Some art historians note that the ancient lighthouse at Alexandria was in this pattern. But minarets have taken many forms throughout the Islamic world. The minaret is a basic part of mosques, but different cultures have a lot of freedom to create their own forms.

Minarets in India assume many varieties, like this on in Jama Masjid, Delhi (above).

Many Turkish minarets are thin and conical, like these in Istanbul.

The modern minaret in the above shot is in the national mosque in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. The minaret is still an evolving art form.

But not all mosques have had them. Their original function was to make sure that the man making the daily call to prayer could be heard throughout the community. Originally, this was done from the roof of Mohammad’s house in Medina, but later minarets became more ornate. Some Muslims have felt that they became too sensual and distracting from God’s message. But they’re central features in most Islamic cities, and they bespeak different thought patterns than what developed in the West.

Most old neighborhoods in Islamic cities, towns, and villages don’t have the grid-patterned street plans of most modern Western cities. You don’t see much linearity in the top photo of Cairo. People’s horizons usually focus on the home, the shop, and the mosque.

Many urban neighborhoods are jam-packed. But into this mixture of intimacy and chaos comes the Call To Prayer several times a day. The voice pierces the streets of haggling merchants and points all towards Mecca. This confirms the idea that the direct relationship with God trumps linear relationships.

The minaret is just one art form that expresses this view of the world. You can explore more of it in mosque architecture and Arabic writing.