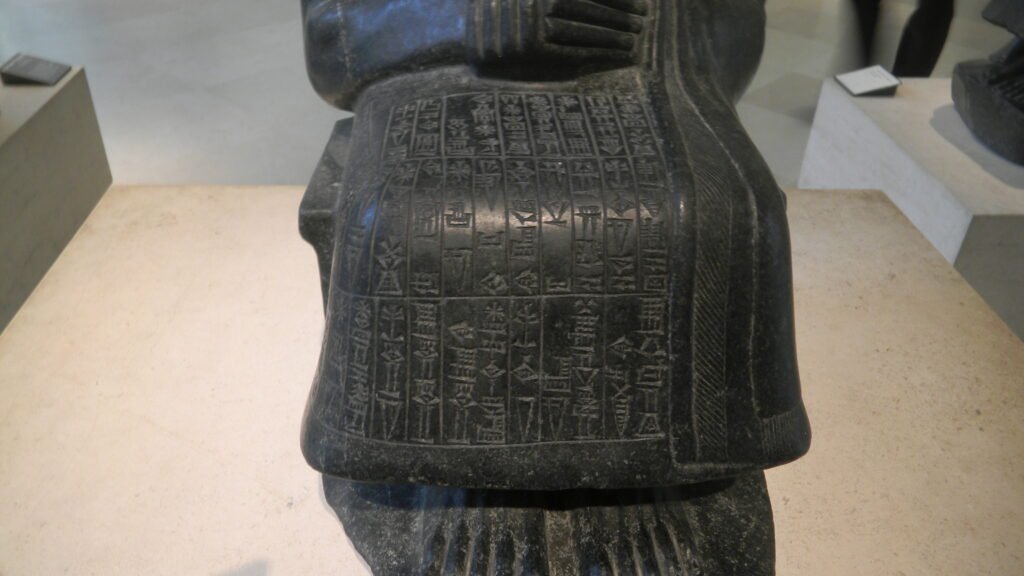

Sumerians created a system of writing that was robust enough for literature more than 5,000 years ago. It was initially used to record inventories and commercial transactions, but in the third century BCE it flowered into stories that made the central importance of territories, political capitals, temples, distinguished personalities, and historical narratives more concrete and widespread. After Sargon conquered the area and founded the Akkadian Empire a little before 2300 BCE, Sumerian tales, hymns, wisdom literature, and lists of kings were translated into the new rulers’ Semitic language, which Hebrew and Arabic descended from. The Sumerian language was in a different family, and it now functioned in a similar way that Latin did in the Middle Ages, as a scholarly lingua franca whose prestige helped spread the most honored traditions to people who spoke in many other tongues.

Some of the most widely shared stories were about the hero Gilgamesh. He is believed to have been a real person and the king of the Sumerian city-state Erech in the 27th century BCE. It had recently won a rivalry with Kish, which was a prominent city-state in the north. Gilgamesh’s century was plagued by wars with other cities and invasions by the Elamites from the east. The dramatic shifts between jubilations and trials inspired a lot of narratives which coalesced around Erech’s most illustrious king. For 2,000 years, stories of his battles with other states, struggles with hideous beasts, interactions with gods, and quest for immortality were written down. People throughout the known world shared them as they pondered the ways of the universe.

The most famous narrative about Gilgamesh was discovered in the ruins of the palace of Sennacherib, who was the Assyrian king (from 705–681 BCE) that conquered Jerusalem. The text is widely considered to be one of the greatest and most influential literary works ever written.

It begins by glorifying its subject. The gods gave Gilgamesh a perfect body. Shamash, the sun god, made him resplendently beautiful. Adad, the god of rain, gave him courage. The deities made him two thirds god and one third human. This is presumably as close as possible to being a divinity while still having to die; the gods kept immortality for themselves.

The narrative then praises the city he ruled. He erected walls, a mighty rampart, and the glorious temple to Ishtar, the goddess of desire and fertility. It tells the reader (more frequently the audience—most of the epic is in poetry and it would have been sung) to behold the walls. The outer wall shines as brilliantly as copper, the inner wall has no equal, and the threshold is ancient. Climb it, walk upon it, and admire its solidity. Its foundations were laid by the seven sages.

But not all was well inside. Although given superhuman strength, Gilgamesh had not been taught compassion, so he was bullying the kingdom’s people so savagely that the gods created a companion for him called Enkidu. The latter was so animal-like that he was covered with hair, and his strength matched Gilgamesh’s. They wrestled and Gilgamesh won, but only after an arduous struggle. Both developed respect for each other and became friends.

Such robust characters would hardly have been satisfied with sharing a couple of beers and a plateful of dates while singing folk songs in a local tavern. Wanting only the most exciting amusements, they decided to venture beyond the Sumerian lands to the cedar forests in what is now modern Lebanon. Since Sumer lacked trees, their wood was essential for building temples, homes, and ships. This was a precious area, so it was guarded by a fierce giant called Humbaba.

Gilgamesh and Enkidu vanquished him, and Ishtar, as the goddess of love and seduction, suddenly found the former irresistibly sexy. She praised his strength and beauty and proposed marriage to him. He bluntly declared that he wanted nothing to do with her. Prostitutes celebrated her fertility in her temple by taking on all comers, and not one of the enormous number of men she enjoyed came to any good. Insulting a vain and passionate goddess is as reckless as calling your CEO a moron in public. In a rage, she ascended to heaven and asked her father, Anu (the god of the sky), to soundly punish him.

Anu granted his daughter’s wish by sending the Bull of Heaven after Gilgamesh and Enkidu. They wrestled with him and killed him, but the combination of slaying Humbaba and the great bull was too much for the gods. Those upstarts were killing guardians of limits in the cosmic order. The gods decided that one of them must die and selected Enkidu as the victim, who then became ill, suffered intensely, shared his vision of the underworld with Gilgamesh, and then perished.

Gilgamesh was heartbroken after his friend passed away. He not only lost his companion, but also realized that he too would die someday. Unwilling to accept his fate, he underwent a long journey to the end of the known world. He aspired to meet Utnapishtim, who had survived the Great Flood with his family and “the seed of all living creatures.” The gods then transported Utnapishtim to this remote location. The old one challenged Gilgamesh to stay awake for seven days and nights, but exhausted after his long journey, he fell asleep. The sage then asked, “How can you conquer death when you cannot even conquer sleep?” He explained that his own long life was an anomaly, because the gods realized that their decision to kill humanity by sending the flood would destroy all people. They allowed him to be the custodian of all species, but this was a one-time event. The lot of every other human is to live for a while, experience some pleasures and pains, and then pass away. No person has a choice; only gods live forever.

But Gilgamesh was given some consolation by being told that he could dive to the bottom of a lake, pull up a plant growing from its floor, eat it, and be rejuvenated. This wouldn’t have enabled him live forever, but it would have restored his youth so he could enjoy a second life. He was able to uproot it, but instead of immediately consuming it, he decided to go back to Erech and test it by letting elders try it first. A serpent then snatched it away while Gilgamesh was on the way back to his city.

The narrative ends where it began. Gilgamesh returned to Erech, but now as a benevolent king who knew and accepted his limitations. He told the boatman who brought him back to climb the great city’s walls and inspect them. One third of their area is city, one third is garden, and the other third is field which includes the temple of Ishtar. He thus learned to stop striving for the impossible and take pleasure in his city’s prosperity and his community’s welfare.

Gilgamesh is similar to the Homeric Achilles by initially being a hero that was too big for his bridle. Both were the best fighters, who could vanquish any enemy, but with their warrior spirits they were uncompromising at first. They were all force and often saw no middle ground. You wouldn’t want either in your living room unless you don’t mind broken furniture and smashed vases. But they evolved as their stories progressed. Achilles mercifully gave Hector’s body to his father, Priam, so he could give him a proper burial. Gilgamesh initially committed hubris several times. He first oppressed his people and then insulted one of the most powerful goddesses. He played a key part in killing two creatures that were valuable to the gods. Gilgamesh then forgot the people he governed and journeyed to the end of the world for his own immortality. But he finally returned to his city, appreciated its beauty, and became a kinder king. Failing to achieve immortality, he learned to enjoy the temporary pleasures of urban and communal living and to take pride in the lasting glory of his city’s monuments.

Gilgamesh also resembles Odysseus by being a hero who wandered the known world, saw many wonders beyond conventional horizons, and then returned home as a wise and just ruler. The two Homeric heroes and Gilgamesh were categorically distinct from other people. Heroes have often stood out so much in Western literature that their distinctiveness became problematic:

- Their strength and spirit were pillars of the social order, but these attributes were so powerful that they could destroy it by raging out of control.

- They were so distinguished that they seemed godlike, but they still had to die. This has often made them tragic figures. Many Homeric heroes knew that they were fated to perish. Although this gives the Iliad a somber mood at times, it makes it joyful at others as the characters experienced life to the fullest extent while they could. Enjoy the moment’s good companionships, stimulating contests, delicious sex, and sweet wine

Heroes in ancient India were instead more integrated with their abundant surroundings. Indra was seen in cosmic terms, as the slayer of Vritra and a bringer of rains. Vishnu was conceived as incarnated many times, and both Rama and Krishna were avatars of him. He has also been seen as the sustainer of the universe, and by the early first millennium CE, was placed between Brahma the Creator and Shiva the Destroyer. Ancient Indians didn’t concentrate their heroes in one place, time, or personage as much as Westerners have, but instead identified them with the larger cosmic cycles and vaster energies. This has made their illustriousness less problematic. They blended into their abundant surroundings rather than stand out as individuals in an environment that was in measured proportions (in Greece) or characterized by dramatic contrasts between life and barrenness (in Mesopotamia and Egypt).

Assumptions that the Gilgamesh stories expressed have remained in the West, and they give us interesting comparisons with India:

Westerners have usually seen meanings as concentrated in specific places that are physically identifiable, and Vedic Indians have more often stressed the whole cosmic field and its abundant flows of energies. Many types of energies could blend, including jyoti, vasu, soma, vayu, vata, ojas, sahas, and savas. They animated the field that all gods and people emerged in. Westerners have more often integrated reality on the basis of what is visible and proportionate with human dimensions.

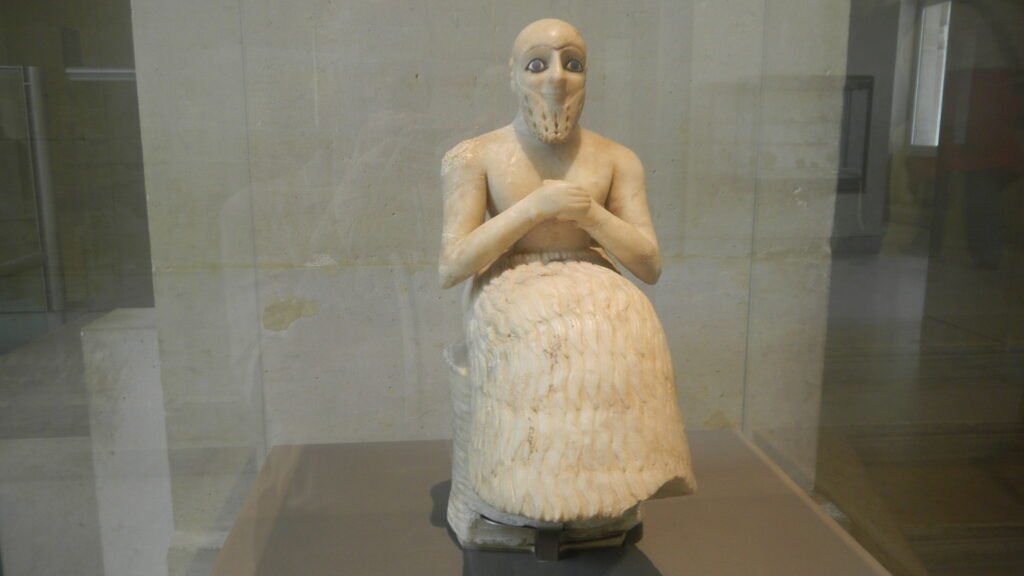

Although Hebrew scriptures frowned on making graven images, other Western societies, including Egypt, Mesopotamia, and Greece, developed traditions of realistically portraying human beings.

They sculpted and painted their heroes, gods, and political rulers, and used these images to illustrate the stories they told about them. Indians didn’t begin to create sculptures and paintings of gods and human beings on a regular basis until about 2,000 years ago. Even the Harappan civilization, which flourished around the Indus River between 2600 and 1900 BCE, made surprisingly few. Few sculptures between that society’s time and the reign of Ashoka in the third century BCE have been discovered.

Egypt, Mesopotamia, Hebrews, and Greeks emphasized written literature, which they stored and performed in prestigious places.

Greece and the Middle East erected monumental temples, wrote engaging narratives, and made realistic images of people and gods early in their histories. They did so in natural landscapes with sharp contrasts which probably reinforced their tendencies to see and represent reality more in terms of distinct domains and less as a single unified field in which all beings and energies are merged. You can see more ways in which ancient Indians thought about reality here.