Traditional Chinese painting has often been based on assumptions that a highly resonant whole is primary in nature and society. It hasn’t focused on linear relationships between distinct objects, as painting in the West often has.

Many Chinese landscape painters have based their art on the concept of emptiness. According to Francois Cheng, in Empty and Full; The Language of Chinese Painting, emptiness allows two entities or domains, such as mountain and water, to be integrated with each other in a holistic perspective rather than making them stand out as distinct.

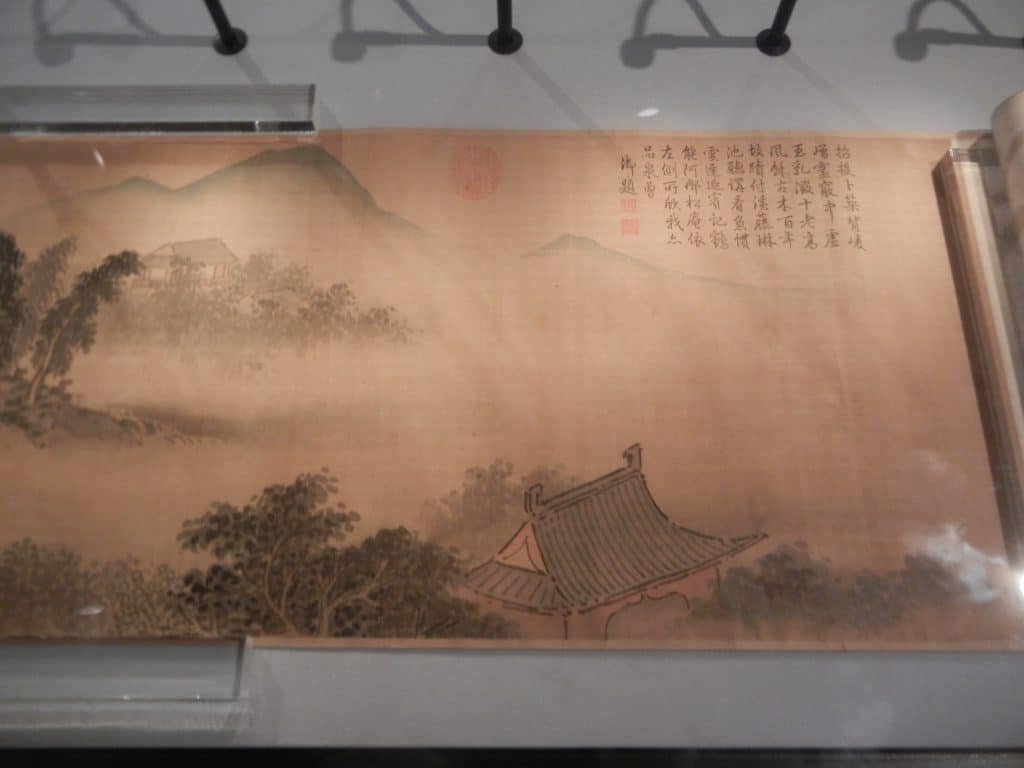

Artists have often expressed emptiness with clouds and mists, which circulate between the mountains and water. Clouds are born from water and rise to mountaintops. A cloud is thus a transition between both, and it shows them as integrated in a process of reciprocal becoming. Both are seen within this process rather than separated into distinct domains. Emptiness and fullness are not distinct states; they transform into each other within a cyclic process as yin and yang do. The emphasis is on an organic whole and the cyclic flow of states within it.

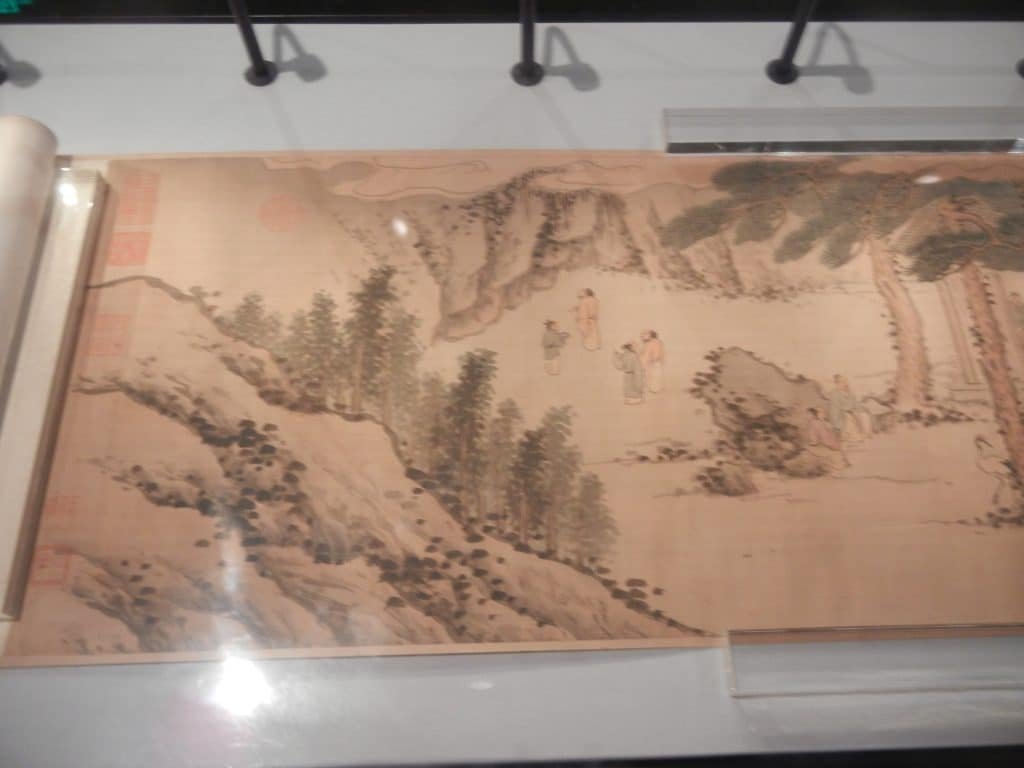

Mountain/water is such a basic complementary pair that landscape painting has sometimes been called mountain and water painting. Mountain is characterized by yang and water is seen as yin. To express their reciprocal becoming, painters have portrayed mists and clouds with diluted ink. This lightens the distinction between the two domains and represents the mutual penetration of yin and yang. Painters have emphasized several other complementary pairs, including rocks and trees, animals and plants, and heaven and earth, and they have portrayed them in balance so that neither dominates the other. Instead, their energies circulate evenly throughout the scene.

As yang contains some yin and yin harbors some yang, mountain has some properties of water and water has some characteristics of mountain. According to the 17th-century painter Shih Tao, the sea can take on qualities of a mountain; its vastness, depths, mirages, tides, and waves express them. He said that the person who perceives the mountain at the expense of the sea and the sea at the expense of the mountain is dull.

Subjects are usually not completely revealed in landscape paintings. Part of a mountain is enshrouded in mist, and part of a house is hidden behind a tree. This technique is called yin hsien (invisible-visible). Nothing is fully disclosed; the cyclic flow of energy within the whole landscape matters more than the distinct object and all of its details.

Viewers’ eyes thus flow around the whole picture in a circle; they don’t linger on a distinct entity and examine the details as though they’re looking at a room’s interior or a street scene from the Italian Renaissance. Space is conceived as a cyclic flow of subtle energies through all domains rather than a three-dimensional grid of points, lines, and distinct objects, which Florentines in the 15th century called most basic in painting.

Concepts of what a brushstroke is also express assumptions that domains are highly resonant. It isn’t just a line or the outline of a static shape. Two brushstroke types are particularly suitable for expressing emptiness. With kan pi (dry brush; it’s spelled gan bi in pinyin), the brush is allowed to absorb only a little ink. The stroke thus balances presence and absence, as well as matter and spirit. With fei pan (flying white) the hairs of the brush are spread out so that a quick stroke allows the middle to remain white and thus express balance between presence and absence. These strokes avoid making a form too finished; if the painter uses too many continuous strokes, the painting will lack life.

Mountain scapes that have influenced Chinese artists look surprisingly like landscape paintings. Hua Shan rises about two hours by car east of Xi’an. Poets and mystics during the Tang Dynasty ascended its peaks. I joined the crowd of modern Chinese tourists and found the entire system of peaks a dreamworld. Cliffs that were almost white jutted straight up, and some were crowned with a row of trees. Clouds sometimes wafted in and caressed the peaks. The cliffsides alternated between smooth surfaces and sharp vertical indentations so that the balance between both seemed like flows of yin and yang energies. On other slopes, trees and bushes grew on ledges so that they seemed balanced with the hard stone. After rising at nearly 90-degree angles, some cliffs quickly leveled off as tops that gently rolled. Peaks and clouds often blended so that the stone seemed like a condensation of the clouds. Both seemed merged into a continuous flow of energy that was sometimes light and soft (yin) and sometimes rough and hard (yang). The whole mountain scape dramatically contrasted with the clear outlines that Greek islands and coasts formed.

An hour west of Chengdu (in Sichuan), Qingcheng Shan rises into a series of peaks that rolls up and down so that it resembles a giant dragon’s backbone. When I was there, the clouds enshrouding the slopes seemed merged with them into a holistic flow of yin-yang patterns. This area became a center of early popular Daoism, which extended the philosophic reflections in the Daodejing to beliefs in a huge pantheon of deities associated with nature and to quests for personal immortality which included alchemical practices. Assumptions of a highly resonant universe reflected some of Sichuan’s landscape.

Most imperial Chinese capitals have been inland. The one exception was Hangzhou, which was the capital of the Southern Song Dynasty (1127 CE to 1279). Although near the sea, the city was constructed by a lake surrounded by mountains that hug most of the areas around its shore. The southern slopes rise four or five blocks from the water’s edge. A fertile plain spreads on the western side, and the Buddhist Lingyin Temple complex nestles against the hill on the far side from the water. Its pagodas, public halls, and grottoes spread where the slopes begin to rise. Palatial wooden meeting halls and serene courtyards are enshrouded by trees, and panoramic views of hills rolling towards the lake and city can be enjoyed from an occasional open space. Verdant tea farms spread between the temple area and lake.

On the northern side of the water, a rocky artificial mountain scape about three hundred feet high was constructed during the Song Dynasty, which locals today enjoy climbing over. The royal palace once presided on the lake’s eastern side. In contrast with ancient Greek cities that were were oriented to the sea, Hangzhou was laid out as a resonant and self-sufficient world that blended the mountainous and watery elements of Chinese landscape paintings.

I found this world stunningly beautiful while walking around the lake. From some spots on the shore, willow trees hung over and framed vistas of the water so that the foliage seemed like a gentle flow of energy that enveloped the whole scene. Clouds and mists slowly flowed around the hilltops so that they seemed to blend into a field of energy in which the hills were condensed clouds.

Mists hovered so low in some places that they seemed to rise directly from the lake. It was thus easy to see all features of the environment as one continuous flow of energy. Although near the ocean, the Southern Song Dynasty’s emperors expressed this integrated world’s resonance as an exemplary aspect of the kingdom and nature as they held court there.

Francois Cheng didn’t cover all the schools of Chinese painting in Empty and Full. The styles and ideas that he explained flowered during the late Tang Dynasty and the Song Dynasty. Other painters employed by courts and nobles portrayed subjects more precisely. Some painted emperors and other elites wearing fineries in their stately courts or majestically riding horses to show them as exemplary. They embodied Confucian virtues, which viewers were supposed to admire and follow. They were thus not shown in the variety of settings or with the diversity of objects that Italian Renaissance painters used for portraying their subjects. Chinese painters instead focused on showing classic virtues and were less interested in depicting average folks and all the details in their material surroundings. Painting regular people only became common around the beginning of the 20th century.

Unlike artists in ancient Greece, ancient Rome, and the Italian Renaissance, Chinese painters and sculptors didn’t typically represent the nude body. The “Clothes make the man” adage is true in Confucian society, in which people’s outfits signify their social rank. Showing subjects impressively clothed thus advertised their worthiness of respect. Assumptions that Confucian virtues resonate have encouraged this focus on exemplary qualities. The painter’s eye was not equally interested in all the objects in the environment, but more on the human characteristics that can harmonize society. Whether a painting was of natural landscapes or people, the emphasis was typically more on resonance than objective observation.

The most influential theoretical work on Chinese painting was written by Xie He in the sixth century CE; he outlined the six principles of painting. The first and most important is qi-yun sheng-dong. Qi means life force, and yun means motion and resonance. A painting should allow the scene’s life force to resonate in the viewer. Sheng means life and birth, and dong means physical movement and exercise. Paintings should convey the vitality of the subject, not just the outer muscles of Greek and Renaissance male figures or the supple curves and creamy skins of female subjects. The inner spirit that generates the subject’s vitality in the first place is most important.

I have always admired Italian Renaissance artists’ development of three-dimensional perspective, which enabled painters to portray minute details of distinct entities and precisely place them in relation to each other. Michelangelo’s David is a perfect distinct entity; it’s strong, proportioned, independent, and able to be scrutinized from all angles.

His painting of God and Adam facing each other on the Sistine Chapel’s ceiling shows both as idealized distinct and masculine figures. God as the perfect entity fashions humanity in His own image, and His creation looks back at Him with full confidence. But some Chinese connoisseurs were unimpressed when Western visitors first showed them paintings from Europe. They were precisely detailed but didn’t portray the circulations of energies that local painting traditions were based on. Some Chinese thought Western artists were mere map makers who didn’t know how to paint. Their scenes lacked life.