Egyptians transferred their energies from pyramid building to temple construction during the New Kingdom (1550–1070/69 BCE). They erected temples that rivaled Giza’s magnificence, and they were as emblematic of their own locations’ sacredness and abilities to unify the entire state as the pyramids were.

One of the earliest great New Kingdom temples and one of my favorite monuments anywhere in the world is Queen Hatshepsut’s shrine across the Nile from Amun’s temple at Karnak. She lived up to her name, which means “Foremost of Noblewomen.” Hatshepsut was the wife and half-sister of King Thutmose II. He died after only three years on the throne, and she solidified her reign while the 18th Dynasty was fairly new by spearheading a comprehensive program for expressing the royal ideology.

The word for the palace (per-aa, literally “great house”) was extended to its ruler. Peraa (pharaoh) now became the term for Egypt’s monarch. She added monuments to Amun’s temple at Karnak (then called Ipetsut–“Chosen of Places), further transforming it from a local temple into a national shrine.

She erected her own temple across the Nile, and used it to synthesize all ideas in the royal theology. The site had long been associated with Hathor, a mother goddess and guardian of kingship. Hathor probably had special appeal to a female monarch. The temple also included shrines to Amun and Ra, and celebrated Hatshepsut’s divine birth and Egypt’s central place in the world.

She built her temple next to a mortuary shrine of a king from the Middle Kingdom (2040–1650/40 BCE), Mentuhotep II (I took the below photo from her temple).

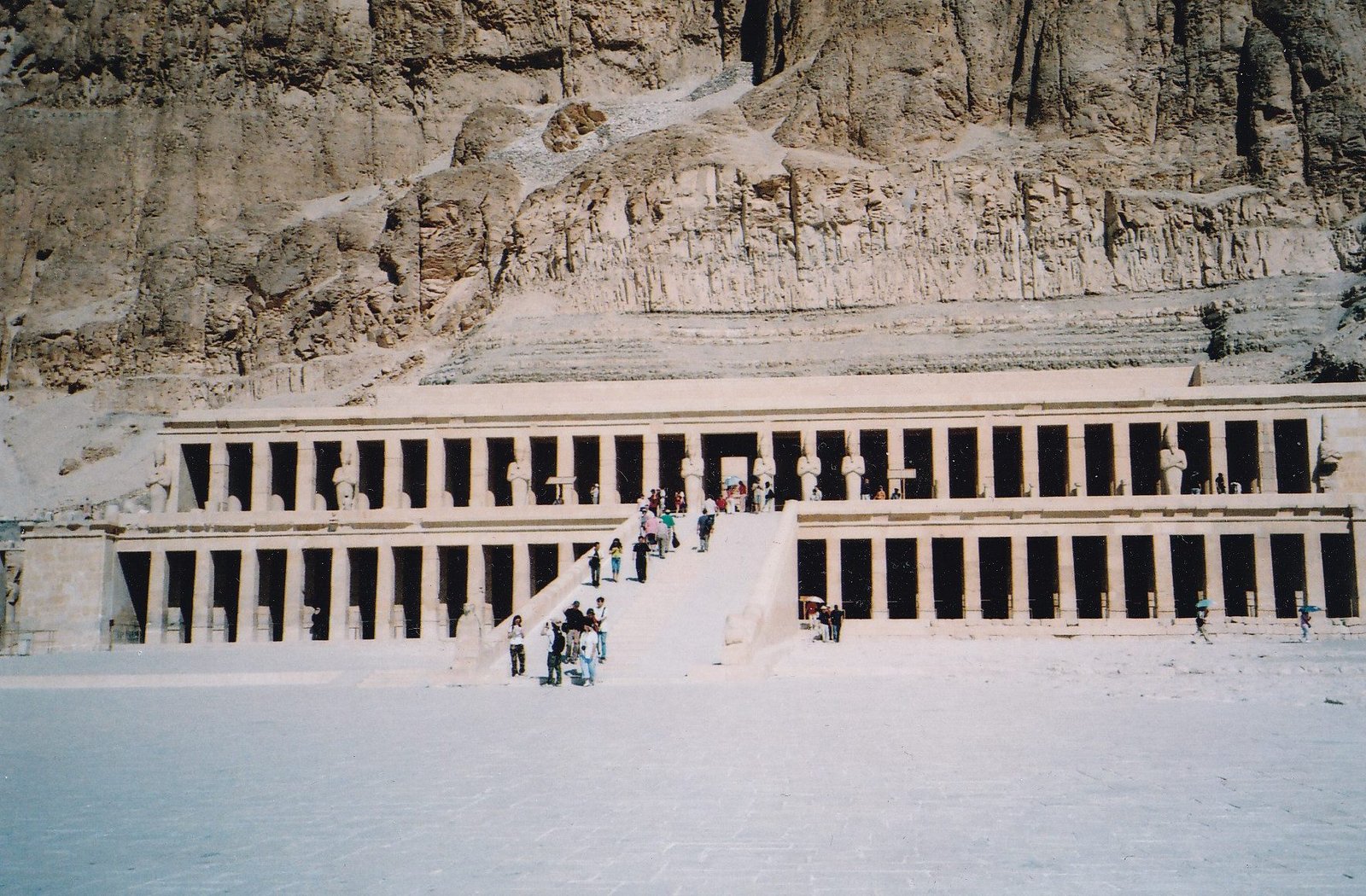

The site had thus already been sacred for several centuries. Both temples were built against a brutally rugged cliff that forms a roughly 500-foot-high wall. Hatshepsut’s fronts it with three lines of columns which rest on top of each other. The bottom two rows flank a wide central causeway whose low gradient made it ideal for royal processions. They led to a courtyard behind the top row. The orderly architecture dramatically contrasted with the rawness of nature beyond the Nile.

The temple’s bottom court held trees and shrubs brought from a legendary land called Punt, which many historians think was on the upper half of Africa’s horn. Egyptian emissaries ventured there to acquire exotic goods, including incense, gold, ivory, ebony, animal skins, and flora. Hatshepsut recorded that she built her shrine as a “garden for my father Amun.” Visitors were immediately immersed in nature’s bounty.

The walls inside the two lower rows of columns contain painted friezes that are some of the most beautiful celebrations of life I’ve ever seen. One shows different species of fish, fowl, and vegetation so realistically that they almost look like drawings in biology textbooks.

Another frieze shows Hatshepsut’s mythical divine birth. Together, the scenes and the architecture’s symmetry project an idealized world of abundance and harmony emerging on the desolate western side of the Nile.

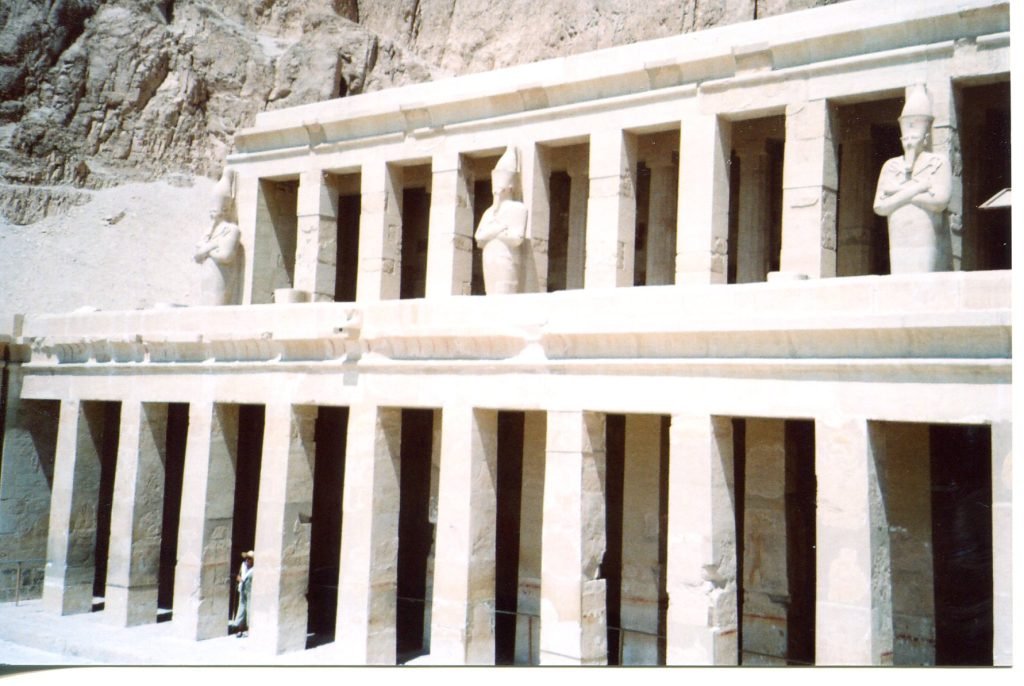

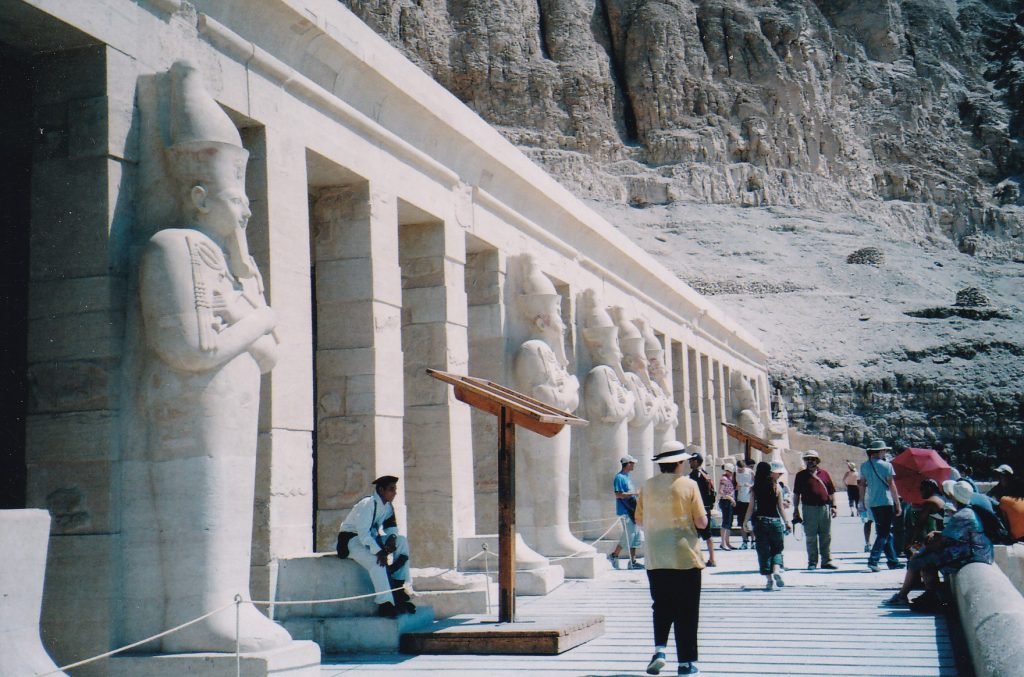

The third row of columns front the temple’s upper terrace. A statue of Hatshepsut in the form of Osiris fronted each pillar (below). To me, her beautiful face made this formulaic representation come to life.

Several of these statues still line the colonnade below.

The portico in the middle of the line of columns opened to a columned court flanked on the left with a chapel for the royal court (Hatshepsut and Tuthmosis I) and on the right by a chapel for the solar cult.

At the back of the court, a large sanctuary for Amun was carved into the cliff. It received his sacred barque during the annual Beautiful Festival of the Valley. Nine cult niches flanked each side of it (below–the chapel for the royal court begins on the left).

The entire court seemed like a bastion of order against the cliff.

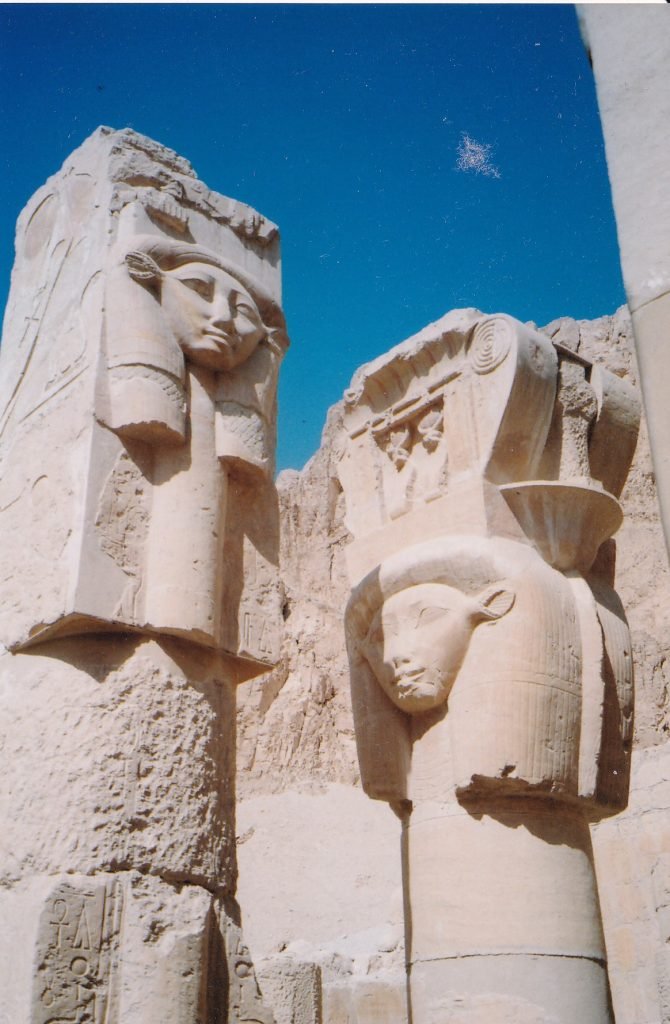

The southern section of the temple contained a shrine for Hathor, with a vestibule with Hathor-headed pillars.

Once a year, priests carried statues of Amun, his consort Mut, and their son Khonsu in portable ships through the pylons of Amun’s temple to the Nile, ferried them across, and transported them to the site of Hatshepsut’s and Mentuhotep II’s shrines. They carried the holy family up Hatshepsut’s temple’s wide causeway, into its upper courtyard, and into its back chamber. The procession was called the Beautiful Festival of the Valley. The portable ships rested overnight at the reigning monarch’s temple and then continued to all the main royal funerary shrines. People with family tombs in the area spent the night with their ancestors, and the statues were carried back to Amun’s temple the next day.

Hatshepsut’s temple set a dramatic standard for expressing order and an optimistic view of the world when the New Kingdom was still in its early stages (this gentleman is resting in the court on its upper terrace).

We’ll explore Amun’s temple at Karnak in the next two articles. Upper-class people in the Karnak area during the New Kingdom could be forgiven for thinking that they were in the most blessed and beautiful place in world history and for wanting to savor its lavishness forever.