King Jayavarman VII, the most prolific builder in the Khmer Empire’s history, added even more luster to Angkor by constructing two goliaths next to its center, where he erected the Bayon. He began them shortly after he took the crown in 1181. Both are just outside the walls of Angkor Thom, the capital city, so they were central features of Jayavarman’s steroidal construction program. Steroidal might not be a strong enough word, since both were virtually cities by themselves.

Ta Prohm and Preah Khan probably functioned as both universities and monasteries. Jayavarmen endowed them so much that he must have wanted them to impart his vision of the universe. He was restoring the empire after the succession crises and wars with the powerful Chams in Vietnam. They were dramatically different from Western universities at that time.

Jayavarman VII had converted to Mahayana Buddhism. But true to Southeast Asia’s tendencies to blend multiple religions, he mixed Buddhism with Vishnu worship, Shiva worship, and Khmer ancestral cults. Ta Prohm and Preah Khan embodied a full and syncretic view of the world as the Khmers saw it.

Jayavarman built the first, Ta Prohm, in 1186 to honor his mother. He conceived her as Prajnaparamita, the Mahayana goddess of wisdom and the Great Mother in its pantheon. He dedicated the other, Preah Khan, to his father in 1191 and saw him as Lokesvara. He was following an old Khmer tradition (Indravarman honored his ancestors at Preah Ko more than 300 years before), but the new king made it as sensational as possible.

These two places were practically cities. Ta Prohm housed 12,640 people, including 18 high priests, 2,740 other priests, and 2,202 assistants. Six hundred and fifteen female dancers performed. Almost 80,000 people provisioned everyone with food, clothing, and mosquito nets. Nearly 100,000 workers performed services for Preah Khan. These numbers might have been inflated to dramatize the places, but just walking through them can make people boost things to supernatural scales.

I found that the biggest Khmer temples can bring out a person’s inner child. They’re so much larger than ordinary life and their forms are so ornate that they can overshadow reason. A laterite wall that’s 3,280 x 1968 feet encloses Ta Prohm. Preah Khan’s outermost wall measures 2296 x 2624 feet. Most of the enclosed areas today are open forest.

The outer walls of Preah Khan and Ta Prohm enclosed the areas where thousands of people lived (the houses were wooden and are thus long gone), so after walking through each complex’s outer gate, I moved through a large open ground before reaching the central section. Anticipation thus built as I proceeded through both places. The architects had a keen sense of drama, as they did at Angkor Wat. Khmers must have designed large temples with processions in mind. I could imagine chanting priests, hundreds or thousands of monks, and elephants carrying the king and his ministers. People’s heartbeats must have quickened as they paraded towards the center.

As they proceeded they would have passed this stately building which might have housed items for rituals and scriptures.

However, the atmosphere transforms quickly at the entrances to the central sections of both temples and Angkor Wat. The construction suddenly becomes dense. The outer section’s open space and the middle’s gravity contrast with each other. People know they’re in a very powerful place when they approach the center.

Both of Jayavarman’s monuments amplify the senses. Small orchestras played gongs and xylophones in each temple’s outer yard, and I could hear the chiming long before reaching them. The large open area allows notes to travel, and the sounds of these instruments carry well. They pierce the sultry air like bursts of energy from the source of creation. Chants and incense within the inner shrines and corridors must have seemed as potent. Sights, sounds, and aromas in both foundations became superhuman.

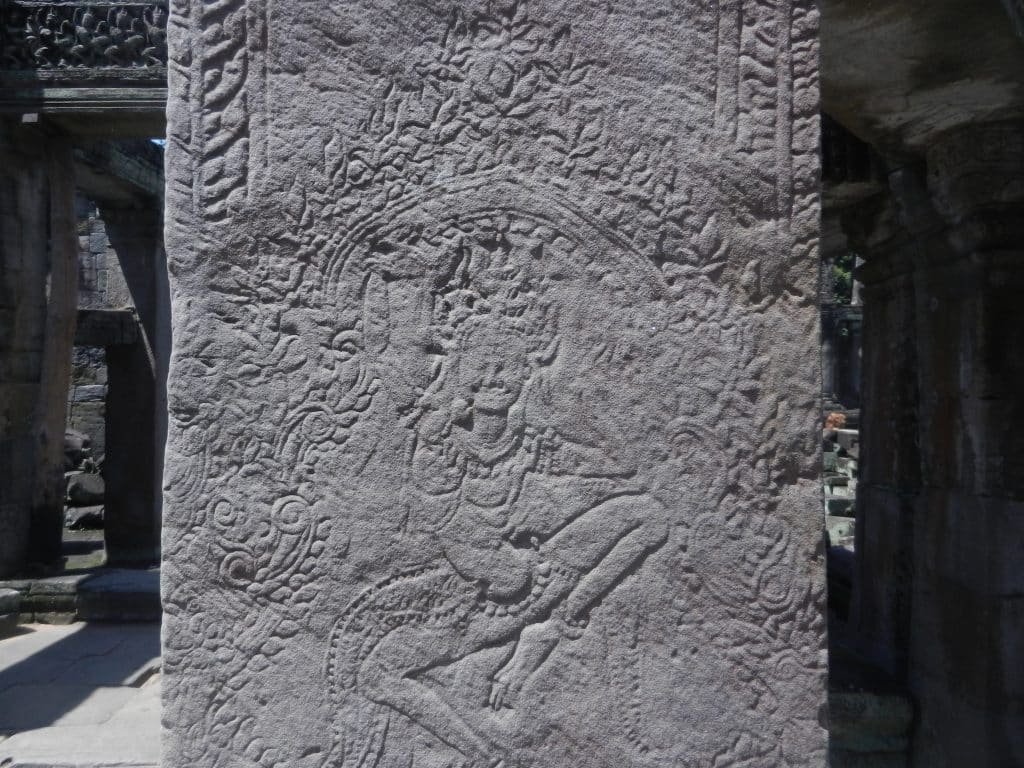

But the two foundations aren’t all muscle. Soft sides balance their crowded architecture and oceanic spaces. Both contain an assembly hall just in front of the central section (called the Hall of the Dancers), with energetically dancing devatas carved on the pillars and lintels.

Each of the four outer walls has an entrance in the middle. Columns flank the wide walkways that lead from each door to a square open space in the center. The pillars are straight and stately, but the hall isn’t huge. If dancers performed there, it gave them a dignified and well-proportioned setting.

Khmers held myths about apsaras (celestial dancers for the gods) emerging from the ocean of milk as the gods and demons stirred it to create the cosmos (many joyfully glide over the snake-pulling scene on Angkor Wat). Khmers thus found it easy to associate dance with the basic patterns of energy that brought the universe into existence. Since the Hall of the Dancers in both of Jayavarman’s complexes is east of the central section, the sun greeted it as soon as it rose. But since both establishments were mainly for Buddhist worship, the art historian Hiram Woodward thought that dancers might have enacted the Buddha’s birth. Both of these themes are about creation. Dancers might have embodied nature’s life-giving energies in these handsome rooms. If so, their symmetry patterned performances in ways that strengthened the empire’s order.

The bases of many buildings in both complexes rise in tapering sections with sumptuously carved vegetal designs covering them.

This custom of constructing ornate plinths follows Indravarman’s Preah Ko. The bottoms of these two temples rise in several curving sections that make them seem to bloom like flowers.

The walls that rise from them are equally opulent.

The lower steps of many Khmer temples from Preah Ko to Jayavarman VII’s works elegantly curve into a point in the middle so that they resemble lotus blossoms and flames when you look down on them. The architects of these two complexes surely didn’t imagine my old sneakers treading on these sacred spaces.

Ta Prohm’s inventory included musical instruments which complemented the visual feasts. Both complexes thus used multiple senses to blend elegance and sensuality to the extent of making residents feel that they were in the gods’ palace.

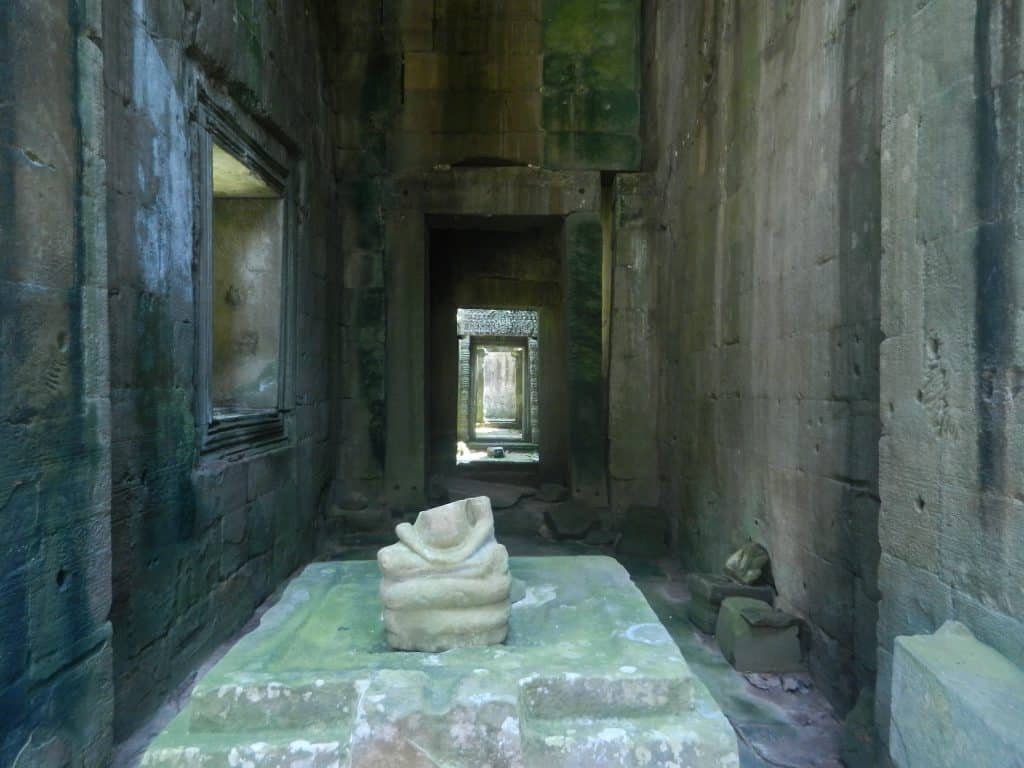

But the gods’ living quarters were cramped. There was no place within the central section’s network of halls and shrines with a view of more than a fraction of the whole complex. After I walked through the Hall of the Dancers, the construction became denser. The central tower isn’t nearly as lofty as Angkor Wat’s and the Bayon’s. The latter two monuments also limit each perspective to a fraction of the whole when you’re in one of the courtyards, but they draw your gaze to the middle spire, which symbolizes the heavens. But because the symmetry in Jayavarman’s two establishments is strictly horizontal, it doesn’t as strongly encourage people to visualize a loftier place that integrates the universe. Both complexes combine regularity with obfuscating complexity and otherworldly elegance. Each had several small courtyards that were combined into a square pattern, like the one in Phrah Khan.

Gleaming pools surrounded the shrines and wall sculptures.

These courtyards dazzled the people who lived at the complexes while preventing them from viewing the whole area.

The corridors in both are very long and narrow. They’re too constricted for groups of students and teachers to saunter and hold informal conversations. They were not meant for free exchanges of ideas and wisecracks. Because they’re arrow-straight, the gaze is hemmed in and forced into one direction. They were good areas for solemn processions and quiet meditations rather than inquisitive student life.

The two complexes did blend faiths more tolerantly than medieval Europeans did at that time. Though Jayavarman was a Buddhist, Preah Khan contains large sections for Shiva, Vishnu, and royal ancestors. The king had no qualms about including every religion that his people followed.

Each temple housed hundreds of statues of gods, bodhisattvas, and ancestors, but many of the long, straight corridors meet at 90 degree angles, and their intersections are small rooms that served as shrines that held a statue.

The corridors and shrines thus formed a grid of squares and rectangles.

This made me wonder if the cults’ rituals were tightly coordinated with each other. Jayavarman was open to all religions in his land, but both complexes gave me the impression that he wanted to control them with a firm grip. I felt that the temples that were supposed to embody paradise were equally focused on his centralized power. Since ancient times, Cambodians had mixed many faiths, ideas, and art forms. But Jayavarman VII devoted so many resources to huge monuments that projected his authority that he might have limited his people’s creativity by not sanctioning alternatives. The amount of building and the innovativeness of royal art sharply declined after the 13th century.

I felt mixed emotions while exploring the two complexes. Their combinations of size and ornateness are spellbinding. But the narrow corridors and courtyards felt constricting. These huge temples/learning institutions represented apex of one of the world’s greatest empires at that time and the beginning of its decline.