It’s easy to take the importance of agriculture for granted, but composers of the Rigveda didn’t emphasize farming. They inherited the traditions of their animal-herding society as they migrated from Central Asia into northwestern India, and praised horses, swift chariots, and large numbers of cows. Greeks at the same time were highly focused on the sea, commerce, and farming, and the convergence of all three helped keep their philosophers oriented to what’s visible and within human scale while Indians became highly developed at thinking about invisible energies flowing throughout a vast universe.

Hesiod, who wrote Works and Days around 700 BCE, had Greek farmers’ experiences in mind when he said that Zeus ordained hardship for humanity. He claimed that his own brother, Perses, tried to confiscate most of their inheritance by bribing the local authorities, and explained that there are two kinds of strife in the world. The bad type causes wars, but the other is good. Potters, carpenters, and bards must compete with each other for livings, and this makes people useful by punishing laziness.

Hesiod then gave advice about living off the stingy soil. Assemble a team of two oxen, which should be male and nine years old for an optimal mixture of strength and obedience. Get a forty-year-old man to help you; he will still be strong enough to follow the plow all day, but without a young man’s urge to seek excitement with other youths. Plow in the winter and spring. Then pray to Zeus for the ground’s fertility and to Demeter for abundant crops, and begin planting.

Dress warmly during the cold months. Wear shoes made from an ox’s hide, line the insides with felt, stitch the skins of firstling kids together for a cape, and put on a felt hat to keep the rain from soaking your head. Walk past the blacksmith’s place, where idle men linger and gossip.

When spring comes, begin pruning your vines. This is a particularly busy time, so get up early and work late. But when the thistle blooms and the crickets are chirping in the trees (in mid-summer, when the heat is most oppressive), you can relax a little. Otherwise, the torridness will exhaust you. Then, when Orion and Seirios arrive in the middle of the sky, cut grapes from their branches and bring them home. Expose them under the sun for ten days, then put them in the shade for five. Afterwards, press them into jars. Then begin your seasonal plowing again.

Hesiod thereby took his readers through the annual agricultural cycle. His horizons focused on daily life on the small farm. Like the Iliad and Odyssey, his perspective was centered on the oikos (the home) rather than the Rigveda’s abundant energies. Hesiod’s and the Homeric poems reinforced each other as mental horizons for ancient Greeks.

Hesiod often sounds cranky and opinionated, and he distrusted women, believing that they’re undisciplined and devious. But he had several positive qualities that Greeks considered exemplary. He was proud of his independence and disliked overbearing nobles. He valued honesty, hard work, proactive planning, and self-reliance. He thus became a model for the sturdy, plain-spoken Greek farmer.

He also valued conventional piety. His writings don’t honor a class of priests, focus on unseen metaphysical energies, or detail elaborate rituals; he was religious in a more down-to-earth way. He recommended offering prayers as you cross a river, respecting Zeus, and giving him sacrifices. His rituals were usually simple, only requiring people to take a quick break from their chores.

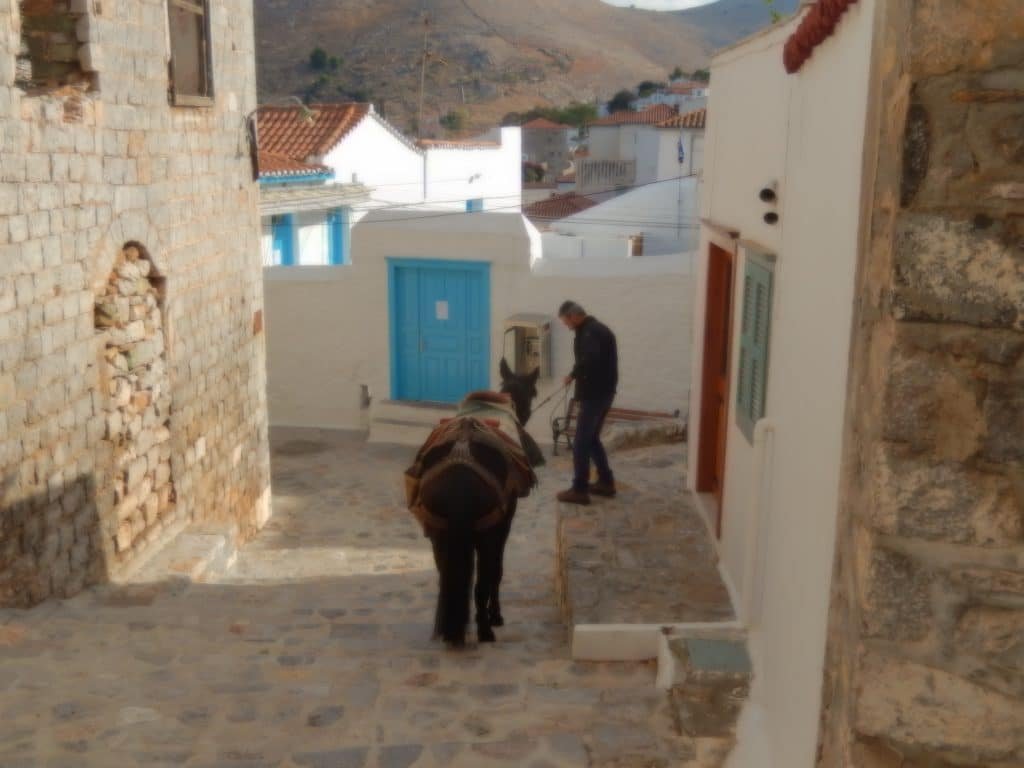

Although ancient Greek farmers wished their soils were more generous, I found beauty in the countryside that was as inspiring as what I’ve seen in the Himalayas. I think a fifty-something Greek mechanic at a gas station in Silicon Valley had this beauty in mind when he said, “Greece is the best place because it has everything: land, water, and mountains.” What struck me was the splendid balance between all domains. Gently rolling farmlands, rugged mountainsides, and seascapes were mixed so that they were in scale with each other. I never saw the overwhelming growth of vegetation in Southeast Asia or the barrenness of Middle Eastern deserts. There seemed to be a perfect balance in nature so that all things limited each other and coexisted in a proportioned harmony.

Hesiod expressed this love of distinctions in his Theogony, which details the creation of the universe and society. In the beginning, all was an undifferentiated void called chaos. Broad-breasted Earth then emerged as a solid ground for the gods. Tartaros opened up as a murky pit in the ground. After these initial dramatic distinctions, Night and Erebos came from Chaos, and Night then gave birth to Day and Aither after she and Erebos made love. Earth bore starry Heaven to cover her and provide a home for the gods.

Hesiod didn’t sing about Vedic energies ranging throughout the universe; he focused on distinct regions and sharply distinguished them from each other as opposites: Chaos and stable Earth, visible Earth and murky Tartaros, Earth and Heaven, and Night and Day.

He seems to have generalized the clear divisions people saw in their environment as the basis of the universe.

The first known Greek philosophers also emphasized contrasts between proportioned opposites. It’s not known if they read Hesiod, but he was as widely appreciated in the Greek world as the Homeric poems were. They at least must have heard people discuss and quote him. As highly curious people, they probably did read him. His work, the Homeric poems, seafaring, trading, and agriculture converged into a cultural environment that shaped what people discussed and the concepts they used. The West’s orientation to distinct and visible objects, proportion, and sharp contrasts was already in place before the first known Greek philosophers pondered the basis of reality. This orientation seems self-evident to many Westerners because billions of experiences converged and resonated with each other, and it has been reinforced throughout history since then. But we’ll see in the next article that a dramatically different mixture of experiences converged in India when Hesiod was praising hard work on the farm and emphasizing sharp distinctions.