Ancient Greeks had a knack for describing concrete events that were bound to specific locations, even when the Odyssey described Odysseus’s travels through the western Mediterranean and when Herodotus expanded geographic horizons to many more cultures.

Herodotus came from a town on Turkey’s southwestern coast, Halicarnassus (the above shot is of Poros, which is a good modern representative of Greek communities that have hugged the sea), and was captivated by the visible world’s diverse places. He wrote about Egypt, Persia, India, Scythia, and Mediterranean societies, describing their customs, histories, and natural features. He traveled to many places and relied on people’s reports about other locations. Some tales are more reliable than others, but he evaluated them and was as objective as he could be. Edith Hall, in Introducing the Ancient Greeks, said that his narratives are so colorful that they have enabled ancient Greeks and Persians to still remain living presences. His description of Spartans’ heroic last stand at Thermopylae and of the Persian king Xerxes ordering the Hellespont’s waters to be flogged bring the ancients to life. Herodotus began the West’s tradition of vivid historical writing, which Thucydides strengthened by detailing the Peloponnesian War.

Indians at that time (the fifth century BCE) were spreading stories about their own historical events. Bards were singing tales that praised kings and glorified their military victories. Stories about the kingdom that the Kuru clan ruled, which was based in modern Delhi’s area, became the core of the Mahabharata. People today still find details about members of the Pandava and Kaurava branches of the clan engaging. They fought over the throne, and tales about them have provided examples of how and how not to live. An elderly man told me that his parents would say, “Don’t be like Bhima” when he was a boy. Bhima was an especially strong warrior, but he had a fiery temper.

However, so many didactic teachings (including the Bhagavad Gita) and so many stories from other places and times were added to the core narrative that they finally dwarfed it by the fourth century CE. The Sanskrit professor E. Washburn Hopkins wrote that the Mahabharata seems like a collection of strings wound around a nucleus almost lost sight of. While Greek historians’ mental frameworks remained bound to specific places and times, the Indian epic expanded into the whole universe. Its temporal framework extended beyond the local events and into a much longer cosmic history and its succession of eras.

The American poet and literary critic Kenneth Rexroth, more comfortable with Homeric human-scale stories and sharp outlines, wrote “The Mahabharata is as inexhaustible and as exhausting as India itself.” But many Indians have found the epic inspiring. Because it’s all-enveloping, it conveys the deepest meanings of the universe. Rexroth felt that the epic lacks perspective because it includes an overwhelming number of substories and subplots, but its perspective is more on a vast and all-inclusive whole than one place or time. Its association with the whole universe has enabled Indians to see it as part of the Vedic tradition, and it has been called the Fifth Veda.

Buddhist and Jain histories emerged in the late first millennium BCE, but they told conflicting stories about religions that kings followed in order to justify their own belief systems; they were less interested in describing events or places apart from their religious agendas. Greeks found recent events in distinct locations fascinating enough on their own, without extending them into religious or vast cosmic frameworks.

The Iliad ends with the Greeks’ funeral for Hector and the Trojans tearfully treading away. The Odyssey concludes with Odysseus regaining his home. The Aeneid foretokens the founding of Rome and the glorious reign of Augustus. The poem exalted him as the culmination of history as much as his statues did.

In contrast with these definite endings and their physically tangible settings, the Mahabharata’s victorious family decided to renounce the world’s politics and left the entire area where the fighting took place. They trekked into the Himalayas, four of them fell dead one by one, and the lone survivor was taken directly to heaven. The epic’s focus thus expanded into a spiritual journey so that the previous warring and the material goods that a lake of blood was spilled over were rendered trivial.

Several other Indian literary classics were extended many degrees beyond a single plot, and the Puranas have been some of the most honored. Brahmins began writing them in or around the fourth century CE, and they portray all cosmic and human history. To be classified as one of the 18 major Puranas, a text must describe five different subjects: the creation of the universe, the recurring processes of creation and destruction, the universe’s eras, histories of political dynasties, and royal genealogies. No particular plot or place is central. Instead, the entire universe’s history is the main idea, and each story is merged into this much larger field. History doesn’t focus on events that occurred within the writer’s lifetime as the books by Herodotus and Thucydides did; its processes are instead expanded into the vast cosmos.

The Puranas and the Mahabharata mixed texts from many political states and literary genres into sweeping narratives. The Ramayana also expanded from a core story into a narrative that was several times longer. According to the Sanskrit scholar John Brockington, it was initially a collection of ballads that bards sang about Rama’s military exploits and other adventures, and the linguistic evidence indicates that its oldest parts were composed in the fifth century BCE. Over time, the hero was more widely venerated and more stories were added. By the time scribes were writing it down, they included every scrap they could find, which came from different areas of the subcontinent. Then in the first to third centuries CE, Brahmins took control of the narrative from the kingly and military class that composed it. They focused on linking Rama’s identity with Vishnu’s and expanding the story’s meaning to cosmic proportions.

Westerners have often followed the three unities that Aristotle said that tragedies should adhere to:

Unity of action. There should be only one plot.

Unity of time. There should be only one temporal setting, which ideally is within 24 hours.

Unity of place. The action should take place in one location.

But Indians have assumed that the locus of unity is the whole vast universe, including all of its cycles of creation and destruction.

This expansion of narratives into many domains beyond a single story also happened in Buddhist traditions, even though the Buddha is supposed to have taught simplicity. He recommended living a balanced existence by following the Noble Eightfold Path: right views, right aspirations, right speech, right conduct, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness, and right concentration. All will help us refrain from harming others and forming attachments to the world, which will impede our liberation from it. But between 300 BCE and 400 CE, the Jatakas were composed. Each is about a previous incarnation of the Buddha, and there are more than 500 of these narratives. So the life of the prince who renounced his inheritance to find liberation from the world expanded into a huge panoply of lives that was as abundant as the palace he left.

The Buddha’s past incarnations were very diverse and colorful. Bhuridatta was the son of a naga (a mythical serpent) king. Wishing to be reborn into Indra’s heaven, he gave up the throne and entered the human world to become a monk. But a Brahmin called Nasada captured him and displayed him in villages around Varanasi to collect money. Bhuridatta’s family learned about this, one of his brothers assumed the guise of an aesthetic, and a sister took the form of a frog and hid in the chignon at the back of her brother’s neck. They found their brother in Varanasi, where he was put on view. His family rescued him and brought him back home; he was ultimately reborn in Indra’s heaven.

In another Jataka, Nemi, a pious king of Mithila, traveled up into the heavens and discoursed with the gods. A lot of other Jatakas sound like folk tales. Temiya hoisted a chariot over his head with his own hands to prove his strength and avoid execution. In another Jataka, Mahajanaka endured a shipwreck and was saved by a goddess. The collection of Jatakas blends a wide variety of tales of the fantastic. They make up an immense field of many types of lives which the Buddha had passed through.

Hinduism then regained strength with a vengeance. The Gupta Dynasty and the Vakataka Kingdom, which together spread over most of India from the north (Gupta) and the central/Deccan region (Vakataka) between the early fourth and early sixth centuries CE, patronized its practices and gave them many new expressions.

Both kingdoms were usually tolerant, so they also sponsored Buddhist art, but their kings often focused more on Hinduism and many Puranas were redacted then. Several were dedicated to an incarnation of Vishnu or Shiva, and these texts dramatically contrast with the dominant Christian theology that emerged in the West around the same time.

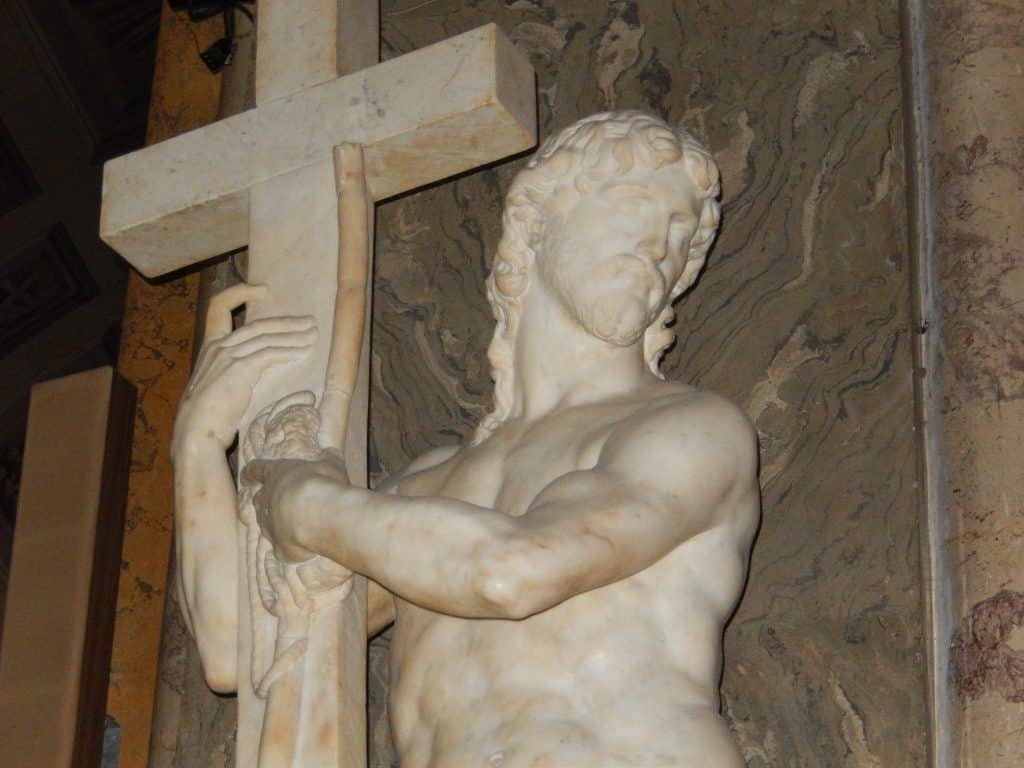

Jesus is the only son of God. He lived and died once for humanity’s salvation. The Old Testament prefigures the New Testament, which details Jesus’ life. He fulfills God’s glory and love. The ultimate expression of God’s power and love is the begetting of a son who saves the people He created from their own sins (the statue in the below photo is by Michelangelo).

This linear view of time became central in the West after ancients had seen time as recurring cycles, but Indian concepts of time were expanding into ever larger repeating cycles. Indians developed a massive corpus of literature around ideas of gods undergoing many incarnations within them.

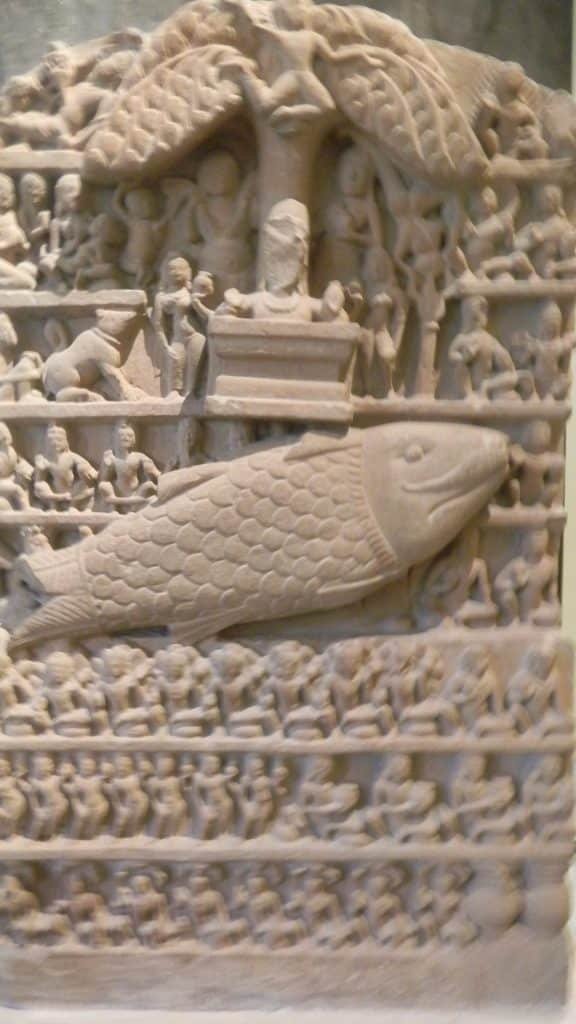

Vishnu was a solar god in the Rigveda, which mentioned him much less often than Indra and Agni. But the Puranas extended his existence into ten imaginative incarnations:

Matsya: A fish that saved the first person on earth, Manu, from drowning during a deluge.

Kurma: A tortoise that allowed himself to be used as a pivot when the gods and asuras (often translated as demons) churned the cosmic ocean to obtain the elixir of immortality.

Varaha: A boar that rescued the earth from the demon Hiranyaksha, who hid it in the primeval waters, by lifting it from their depths on his tusks.

Narasimha: A half-man/half-lion hero who vanquished a demon king called Hiranyakashipu. The evil monarch was Hiranyaksha’s brother, who tried to avenge his death by persecuting Vishnu’s devotees.

Vamana: A dwarf who conquered King Bali (who had usurped Indra’s powers) by duping him into letting him rule the area he could stride in three steps. He suddenly grew to encompass the whole universe.

Parashurama: A hero that killed a thousand-armed king who stole his celestial cow, which could grant all wishes.

Rama: The hero in the Ramayana.

Krishna: Arjuna’s chariot driver in the Bhagavad Gita, who taught him about the universe and the way to salvation. Some lists instead include Krishna’s elder brother, Balarama, who was a plowman that was fond of wine, as Krishna enjoyed women.

Gautama Buddha: The Hindu tradition’s enormity engulfed him too.

Kalki: The future incarnation of Vishnu at the end of the current series of temporal cycles. He will appear on a white horse, brandishing a blazing sword at the end of our temporal period to punish sinners and purify the cosmos for its next rejuvenation.

Like the collection of Jatakas, this sequence of incarnations transcends many times, places, and life forms. Some incarnations vary in different texts, but all detail a long sequence of lives. Boundaries between stories, between their settings, and between characters are flexible enough to allow many identities and places to merge into a larger field that encompasses the whole universe.

Ancient India and ancient Greece held different basic assumptions about narratives. The field that gives them their meanings was often temporally and spatially localized in Greece and expanded to the entire cosmos in India. These different assumptions about the locus of meaning converged with many other aspects of culture, including language, music, architecture, the natural environment, and mythic gods. Narrative structures and ideas of time and space can seem so basic that they’re not questioned, but they’re characterized by the whole cultural landscape.