My attraction to northern Thailand strengthened when I visited minority groups in the hills. Many non-Thai minorities live in northern Thailand, and they offer a treasure-trove of customs. The largest group is the Karen, who probably migrated from southwestern China or southeastern Tibet to Burma and Thailand. Lahu and Akha people live at higher elevations. Hmong people also reside in Thailand; some were already there when King Mangrai ruled at the end of the 13th century, but most came within the last 200 years. Many Hmong are refugees from battles between Burma’s government and Shan groups fighting for independence near the Thai border. All these cultures add to Lan Na’s diversity of lifestyles.

Sadly, a lot of minorities have been exploited. Big companies have bought a lot of land in the north for tourist resorts and large-scale farming. They have taken common woods that locals used to use, and this has left many without enough land to feed themselves. Other minorities have lost their homes through legal manipulations that they don’t understand, and some have been forcibly resettled.

My taxi driver wheeled out of Chiang Mai and up into the hills. He hung a left onto a narrow dirt road that twisted for about a mile, stopped in a small clearing, and pointed to where I should walk. A path led through thick brush and into a compound of low stilt homes. Each was a typical Karen house, with a bamboo floor, wooden frame, thatched roof, and no outer walls. People cooked and ate in its single spacious area during the day, then unrolled mats in it for the night’s sleep. Five middle-aged and elderly women sat on the outer edge of a home. They wore bright red and blue striped sarongs and blue tops, and some of their mouths were red from betel chewing.

A lot of Karen live between worlds that are hard to integrate. They traditionally stress harmony with spirits, village leaders, and neighbors. Many villages have a person who leads their rituals, and he watches members’ behavior to keep it within communal rectitude. The ancestral guardian spirit (bga) provides protection and comes to the aid of all members of the lineage. The oldest woman in the lineage officiates at an annual rite to preserve the relationship with the spirit, and all members are expected to attend. Karen strongly disapprove of divorce and adultery. Both require expensive rituals to restore order, and transgressors are sometimes run out of the village because violating marital ties offends ancestral spirits. But the modern world has ruptured this mixture of coziness and caution. Missionaries converted many Karen to Christianity, and others embraced Buddhism. Since Karen typically live in the lower elevations of uplands (around 2,000 to 3,000 feet), they reside between the Thais on the valley floors and other minority cultures higher up. They thus often serve as go-betweens. Many work in lowland towns and periodically return to their communities. How did this contrast between a conservative culture and recent dislocations affect the people in this village?

The one person who spoke English was in her mid forties. She told me that she had married a Thai man and then divorced him because he drank too much whiskey, and that she didn’t have any children. Without a family, she represented her people’s traditions to modern tourists and commuted to Chiang Mai for a class on becoming a guide.

The other women were elderly and seemed more settled in traditional life. They were so cheerful that they reminded me of carefree schoolgirls. But an old man who joined them seemed traumatized. He was practically toothless and dark green tattoos covered his chest. He said nothing and his eyes appeared forlorn. I wondered if he had been forcibly uprooted from his world. Did he suffer in Burma? It seemed indelicate to ask.

My guide then walked with me to a village of the Lahu people. This ethnic group migrated into Burma and Thailand from southwestern China. Most of them don’t form clans; small families are their main social groups. The Lahu honor village and nature spirits and stress communal harmony by giving them offerings to avoid conflicts. They prefer to keep things safe and familiar and avoid wandering far outside their community, where spirits can be more dangerous.

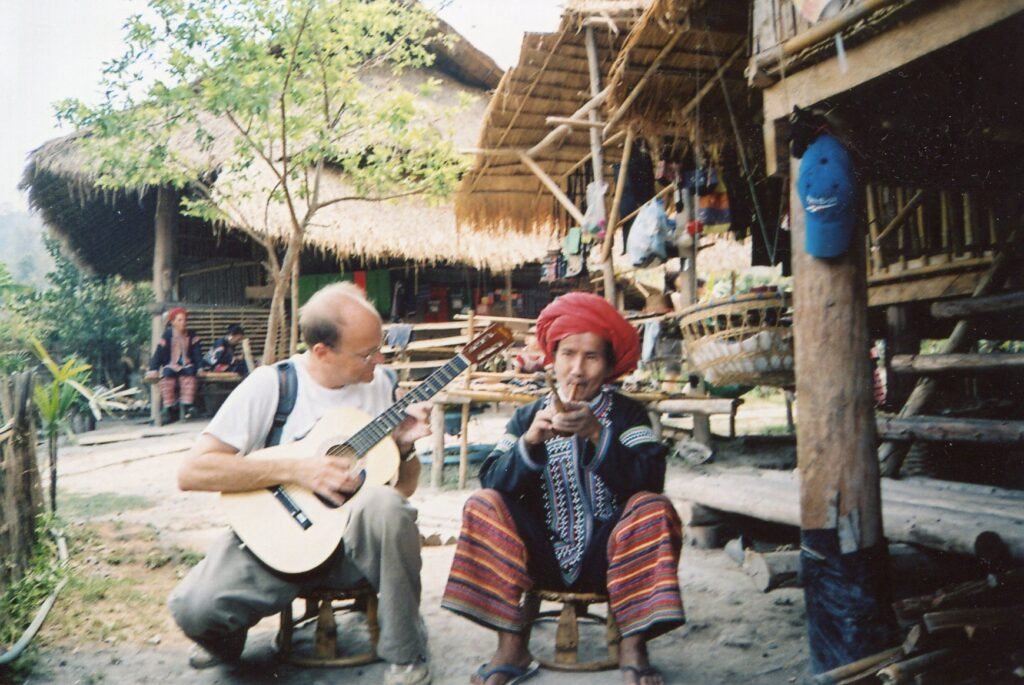

I played guitar for an elderly man and wife, and he dashed into their home and brought out a small mouthorgan. Many people in mainland Southeast Asian hills play them, and they’re popular among the Lahu.

Some of their priests perform on five-foot-long pipes in ceremonies. We sat shoulder to shoulder and played a few tunes. He then stood up and began to dance in steps that seemed preplanned rather than improvised. Lahu enjoy dancing during their traditional New Year festivals, when people go to nearby villages to share food and dance. This affirms communal harmony. Maybe this man’s hoofing brought back happy memories; his mellow smile suggested so.

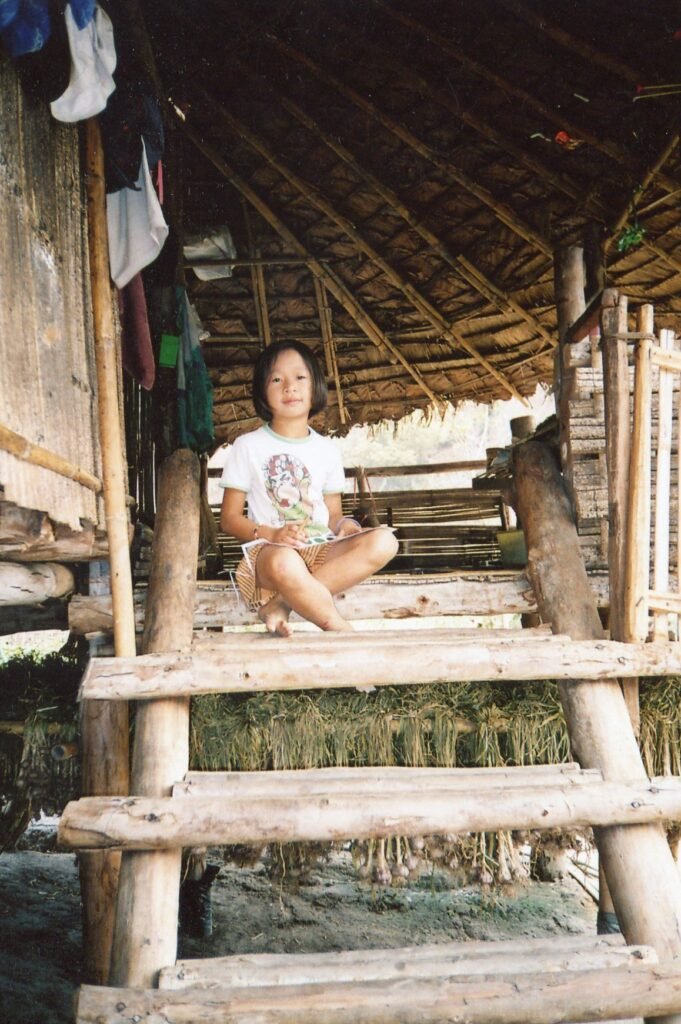

My guide and I then walked uphill and arrived at a circle of one-room houses on low stilts, with bamboo walls and thatched roofs. About 12 teenage Padaung girls with shiny brass rings around their necks sat under tiny pavilions in front of the houses. Most were knitting and politely smiling, and two were reading fashion magazines. Some impoverished parents sell their daughters to be manufactured as “long neck” people. They’re forced to squeeze the rings around their necks, which depress the shoulders so that they appear long. This is an old custom among Padaung tribes in Thailand and Burma (they’re a subgroup of the Karen). Some reasons that have been cited for it are feelings that it makes women look graceful, associations between their long necks and dragons (which some Padaung venerate), and men’s desires to make their women unattractive to other tribes so they won’t abduct them. There’s no consensus about a single reason, but when a Padaung girl is two to five years old, the first few rings are placed around her neck with a ceremony (some girls wear a single piece, which is coiled around several times). A new circle is added every year until she becomes an adult.

One girl was playing a homemade guitar with only four strings and a rough-hewn body. I sat with her and jammed along. Three of them played and all could position their fingers into chords quickly, so they had spent time practicing. One smiled when I strummed the same chord at the same time. I then sounded higher notes that harmonized with hers.

The girls only knew a few chords; they had not learned scales or higher notes than ones played near the end of the neck. But as I walked back to the Karen village, high tones rang through the brush. The lack of tempo made me think that one of them was experimenting. It seemed that she hadn’t thought of playing anything besides chords and low notes before and that she was discovering a new dimension of music. I enjoyed thinking that I had added something to their lives.

Back in the Karen village, a burly young man with a deep and soft voice said, “We have been hearing your guitar all day. Will you come into our home and play for us? We will cook dinner for you.”

It was another typical Karen house, on three-foot stilts, with a bamboo floor, wooden frame, thatched roof, and no walls on three of its sides. I had to get used to the floor’s bending as I walked on it, but I soon enjoyed the rhythm because I felt in harmony with nature. The open sides of the house allowed us to see neighbors’ homes and the trees that surrounded us. This was one of my deepest impressions from that day: being immersed in nature and the community, with no walls between places. As in perspectives in Thai wats, paintings, and neighborhoods, everything mingled in a flow that was both animated and soft. Even the floor rippled like a river. Millennia of living in such surroundings probably encouraged people to develop and emphasize this kind of perspective in their arts.

The elderly Karen women I had met earlier were sitting on the floor knitting, chatting, and giggling. One got sleepy and curled up where she had been working. She woke up about an hour later, picked up the bright red and blue threads, and started to knit again. There was no time clock or factory supervisor, only family and friends. Of course I was only seeing the happy sides of traditional village life (there were no dangerous animals around), but I longed for more when I got back to town.

Many Thais do too. They created a popular genre of music about a villager moving to Bangkok to find work and missing the country. Since the big city has grown severalfold since 1970, lots of Thais have heartstrings attached to the old farmlands. The dining room of my hotel in Bangkok displayed a large painting that looked just like the view from the inside of the Karen home I was in. I always lingered on it before heading out to the busy streets.

My Karen hosts brought me one of their traditional meals: rice with an assortment of vegetables and sauces to pour over it. They served it on a large banana leaf. I had eaten on them in southern India and always had to make an effort to avoid spilling food on my lap because they were so flimsy. But I enjoyed this timeless village experience because all objects came from nature.

As I was eating, the wife of the Lahu man that played the mouthorgan slowly walked over from their village. Her stiff waddle suggested arthritis. She stood by the edge of the house and watched us for a while, but spoke a different language and thus couldn’t communicate with anyone. She left after a few minutes, looking bored. Life seemed good for some of the Karen, but the Lahu woman had fewer people to relate to.

The man who offered me dinner was going to walk to his father’s village the next day, and he invited me to join him and sleep there. Alas, I had to fly down to Bangkok two days later, but I was happy to see that he still lived a traditional life, and that he had a direct bearing that exuded peace. My guide then sat down with us and leaned over a worn paperback book to study for her class. She was now wearing jeans and a bright red T-shirt.

So the site was neither idyllic nor sordid. Most people welcomed my extensions beyond tourist-actor roles. They also enjoyed sharing music. Their degrees of happiness and abilities to preserve their pasts seemed to differ, but I felt deep respect for all of them because of their dignity.

The day also transformed my perceptions for a while. When I returned to Chiang Mai, the city that I formerly thought swung looked like a giant octopus. Streets with wall-to-wall concrete buildings lining both sides seemed like tentacles spreading all over the land. What I had found vibrant now looked monstrous.