Back to Europe. After exploring Indian and Middle Eastern art, where better to land than one of the most influential churches in history. The abbey church of St. Denis is no less than the birth place of Gothic Style, which is one of the world’s greatest art forms.

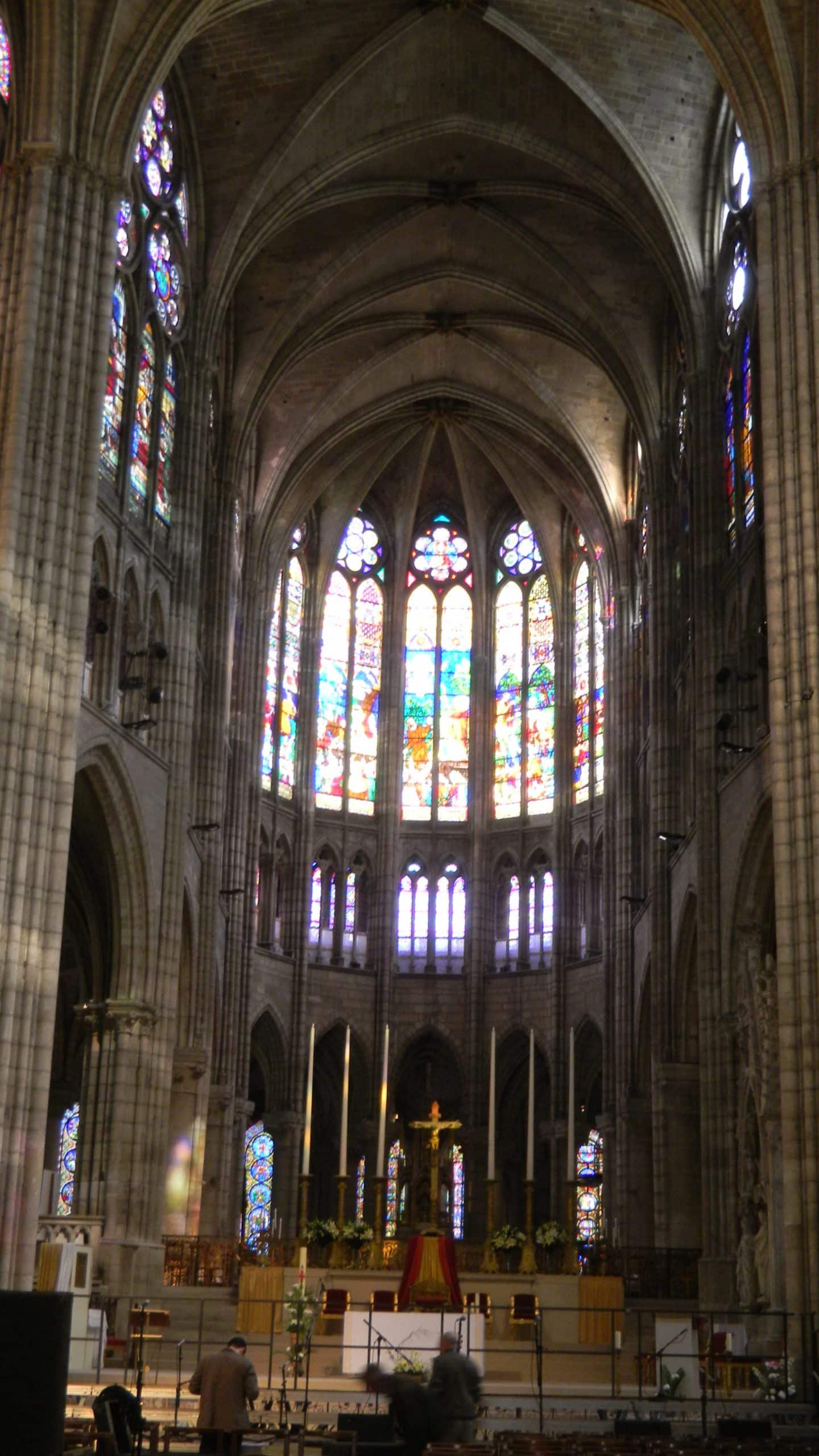

Above, you see a stunning contrast with the vast panoramas in Indian art, in which all life forms are integrated. Here we see Western culture’s use of lines to clearly partition domains in an order that’s rational and proportioned. But at the same time, these lines rise into the heavens far above, and aspire for a spiritual realm where shining light replaces the firm columns. This is one of the most inspiring things about Gothic style–the lines that divide the building try to transcend themselves and reach a more heavenly existence. The architects wanted to stress a linear order that rules the universe (a focus inherited from ancient Greece and Rome) and overcome it at the same time. Gothic churches portray both the proportioned material world and the heavens.

The frieze at Mamallapuram, in India near Chennai, is similar and different. It too expresses a spiritual realm in which all things are integrated. But it does so without the firm lines and clear proportions–it does so without the ancient Greek legacy.

And it does so without raising the spiritual world so far above us that we have to strain our necks to see it. The Catholic tradition says that there is only one locus of divinity–access to the spirit is through one god, one savior and one church. But the Mamallapuram sculpture portrays a life force that all are integrated in, and which has many openings. So the world is more unified than hemmed in by lines, and more vast than proportioned.

But I’m racing ahead. Most of what you see in the photo of the church of St. Denis was actually built about a century after Gothic style was born. As beautiful as the above work is, the most historically interesting parts of the church are at the two far ends–the mid section we’re in was updated a little later.

The first Gothic facade differs from Indian art’s panoramic perspectives. The West advanced beyond its simple Romanesque forms in its own terms.

This was the first part of the church that Abbot Suger remodeled as he pioneered Gothic style. A new world was about to open up.

The entrance was the first that expanded from the flat Romanesque planes and synthesized sculpture with the architecture.

The Last Judgment (pictured above) over the main entrance begins to bring the stones to life. But it doesn’t show all life forms integrated in a field of energy, as Indian art works like Mahamallapuram do. It:

1. Centers you on one great figure: humanity’s one and only savior.

2. Portrays all figures in the scene in geometric order.

This geometry is like the facade–proportioned. The facade is divided into three sections by huge wall buttresses. The Last Judgment is over the middle door, so the entire facade focuses your gaze on Jesus, and this all-important event. The Last Judgment is a once-and-for-all affair. Christianity doesn’t believe in the vast temporal cycles of repeating eras, or in long processes of reincarnation that much Indian thought has focused on.

As the West moved from Romanesque style to the more life-like images of Gothic style, it used the ancient Greek focus on linear order and static geometric ratios. Before the late 20th century, it was common to sharply divide the ancient, medieval and modern eras. But there’s a lot of continuity in the entire Western tradition. All eras have enjoyed linear and rhythmic clarity.

But Abbot Suger was pioneering new standards of realism, and the entrance facade of St. Denis was only a beginning. We’ll enter the church in the next post on Gothic Style and see that this developing realism was more complex, and potentially troublesome, than Suger probably imagined.