France’s King Francois I played a leading role in importing the Italian Renaissance to his land while reigning from 1515 to 1547, and his physique and personality ensured that he would do it dramatically.

He was over six feet tall and full of energy, libido, and ambition. The painter Jean Clouet portrayed Francois (above) projecting so much self confidence that even his athletic frame and full beard seem too small for him. As he tried to extend his persona beyond all physical limits, he helped expand France’s horizons to the Italian Renaissance.

Francois wasn’t just a physical phenomenon; he loved art and talks with learned people. So he went the extra mile for culture. Francois brought every Italian painting he could get his hands on to France, transformed the Louvre from a fortress into a luxurious palace, and gave Leonardo da Vinci a home in his last years.

Francois’ court moved around the country a lot, so he bejeweled it with a network of Chateaus. In them he met his officials, hunted, womanized, and patronized art. Poetry, song, sporting matches, and revels became fashionable as the king traveled between palaces to govern his realm.

The palace of Fontainebleau (above and below) was one of his pride and joys. He enlarged it by building a long gallery between the royal apartments and a monastery that Louis IX founded in the 13th century. Inside that row of windows on the middle floor (below), he commissioned art that set standards for how France would enter the modern world and make Western culture more creative.

King Francois I was attracted to two contrasting personalities. The Italian painter Raphael was the paragon of taste and restraint. His proportioned works set standards for classical balance, which no one has ever bettered. But the other painter was a rebel.

Rosso Fiorentino reacted against Renaissance ideals of measure by painting the opposites: bright colors and intense emotions. Some people thought he was perverse, but he helped establish mannerism as an artistic style. Francois brought every Raphael picture he could grab to France, made Rosso his principal painter, and put him in charge of decorating the Fontainebleau’s great hall (above). Magic was bound to happen.

Francois commissioned Rosso to fill it with paintings. He had other artists add statues and plasterwork. The paintings are challenging; they’re crammed with symbolic meanings that historians still haven’t agreed on. Francois also kept scholars around, including one of Northern Europe’s most renowned humanists, Guillaume Bude. The dense scenes evoke over-busy male brains–guys discussing big and useless ideas long into the night over generous amounts of alcohol. But France’s mental horizons were growing beyond its medieval past, so we can understand the enthusiasm that went with the discovery of the Italian Renaissance and ancient art.

The Royal Elephant which Rosso painted (above) suited those imaginations, the king’s desire to project his own image, and Rosso’s itch to flout conventions.

The painting is an allegory of Francois’ good rule. He’s the elephant–since antiquity this noble animal had symbolized royalty and wisdom. The stork behind his left front leg stands for filial piety.

Saturn’s three sons stand around the elephant, and they represent elements: Fire (Jupiter), Water (Neptune), and Earth (Pluto). The revelers on the left side of the painting might symbolize bestial passions, which the wise and mighty elephant overcomes.

There are plenty of other symbolic images around the elephant.

Francois was doing a similar thing that the Elector of Heidelberg did at Heidelberg Castle. Both used figures from the classical and Christian worlds to project themselves as the world’s best rulers. This was common in 16th century Europe as cities, literacy, commerce, and court bureaucracies grew. Francois was using every symbol he could to bolster his image in an increasingly complex world.

His method contrasts with the Elector of Heidelberg’s simple linear order. Francois’ style may seem bombastic today, but they engage the viewers’ emotions as well as their intellects. Rosso Fiorentino is in full flight in the below scene. The contorted bodies and white-knuckle emotions are the mannerist style, and they dramatize the death of Adonis.

Some modern scholars claimed to finally understand the paintings’ complex symbolism. Many scenes are of death and misfortune. They might have symbolized the dangers of letting your passions run wild.

But the above painting is about the education of Achilles. The best fighter from ancient Greece’s earliest written epic, the Iliad, is learning fencing, swimming, lance throwing, music, and hunting. This scene might illustrate the importance of learning.

The art historian Erwin Panofsky saw a pattern in these paintings. The death and destruction stuff is more concentrated towards the end of the hall by the royal apartments. Scenes that show the universe in order are more numerous near the chapel’s end. Francois might have wanted his visitors to feel a spiritual transformation as they walked from his living quarters to the chapel.

That’s pretty in theory. But in reality he instigated wars that exhausted France’s finances. But many French people adored him over the ages because he represented glory and style. And though he was a bad student of his own art, it did some glorious things for France and Western civilization.

Classical sculptures pose between many of the paintings. They range from self-confident beefcake–

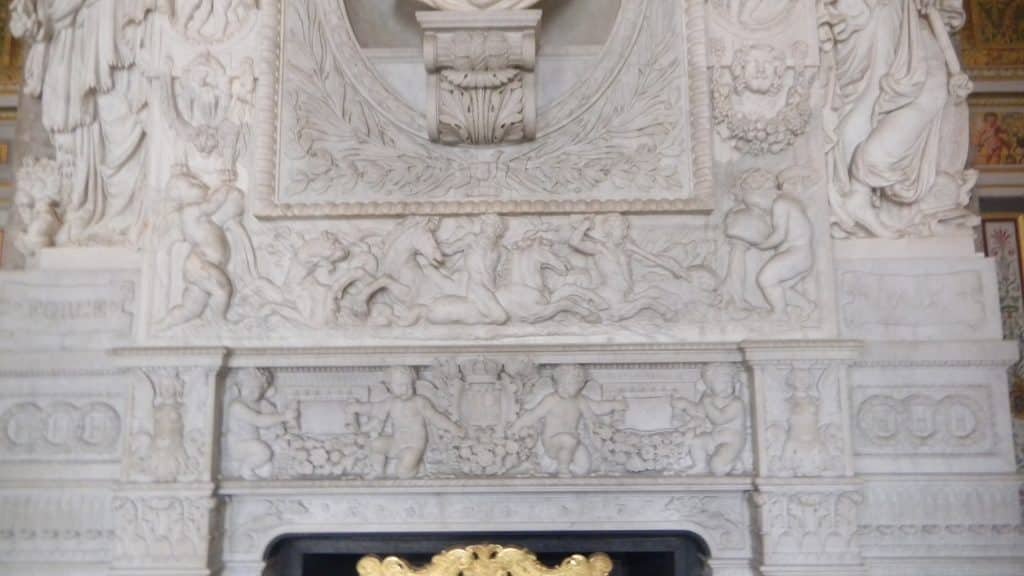

to pinchable cherubs (sculptures of cute babies in their birthday suits were fashionable in ancient Rome).

Francois spread many facets of the Italian Renaissance at once. In his enthusiasm for it, he collected and produced every type of image he could and gave Western culture many gifts. Linear perspectives and themes from ancient Greek myths added to Northern Europe’s horizons. At the same time, French culture blended with them to give the West new ways to represent reality.

Artists in Rosso’s wake developed the Fontainebleau School. They used dramatic colors, but in soft and playful ways. They went for grace more than Rosso’s intensity and added whimsy to Raphael’s classical proportions.

You can even see whimsical colors, human forms, and architecture in the ancient Roman scene above.

French joie de vivre didn’t come from Italy–it was in full glory in High Gothic Style. But it got a huge burst of energy when Francois imported Italy’s expressions of both rationality and fancy at the same time. French culture favored both in different times–the former during Louis XIV’s reign at Versailles and the latter in modern art.

This happened in literature too. All that cultural abundance is probably why my hair was standing on end after exiting Francois’ palace and exploring the grounds.

Francois patronized Rabelais for ten years, who had been an unwanted child that was forced to live in a monastery. But he grew into one of the most learned people of his time and a literary genius, mastering Latin, Greek, and Hebrew and reading widely in history, geography, jurisprudence, and literature. The cultural historian Jacques Barzun noted that Rabelais expressed the world’s abundance by:

- Measuring things with huge numbers, including the 9,764 theses that Pantagruel posted (95 were enough for the fastidious Martin Luther), distances in travel, populations of newly discovered lands, and war casualties.

- Enormous lists of things.

- Floods of words, including synonyms for things, ideas, sensations, and parts of the body. He also created unknown compounds from Latin, Greek, and French.

His linguistic exuberance and joy in the world’s variety matched Shakespeare’s. Barzun wrote that Rabelais leaves the reader exhilarated and that he expressed the dawn of modern Western culture. He traveled an astronomical number of miles beyond that monastery, with eyes and ears wide open.

In the mid and late 16th century, the poet Pierre de Ronsard expanded ways to appreciate nature and express love by adding modern words with Greek and Latin roots and resurrecting the 12-syllable line, called Alexandrine. In the later half of that century, Michel de Montaigne wrote details about his own thoughts and feelings and expressed his appreciation of a world of many cultures and nations. Both writers expanded perspectives of the outer and inner world.

Francois imported everything he could from the Italian Renaissance, and France’s artists and writers synthesized them with their own culture and enhanced the West’s ways to perceive, create images, write, and think. We’ll explore France’s heritage from the 17th century in a later article. Much of the world is still basking in it.