People in the 13th century classified their world so that every being had its place in a universal system. Their world included some strange creatures.

People back then had big enough imaginations to envision a lot of bizarre life forms. So where were they coming from when they carved these on Rouen Cathedral in France?

A previous article on medieval philosophy explained that folks who built Gothic cathedrals saw them as depictions of the whole universe in which everything was in its place. And they meant everything. Several writers in the 13th century created huge encyclopedic books. St. Thomas Aquinas published his Summa Theologica, which integrated Christian doctrine and ancient philosophy.

Vincent of Beauvais also went after universal and comprehensive knowledge when he published his Great Mirror. This collection of books put all the beings that God created, all moral instructions, and all historical events in their places in the cosmos.

People who built Gothic cathedrals were doing the same. They saw the universe as a hierarchy of beings which God created. Nine levels of angelic souls hover over us, and beasts and demons grovel below us. So these strange-looking creatures in the photos are part of this divine hierarchy. They fleshed it out for the local townsmen. But there were higher levels in this schema.

Such as the world that ordinary folks live in. The south portal of the Basilica of St. Denis, in a suburb a little north of Paris, has two vertical lines of people doing their daily jobs. Here, bakers earn their daily bread with the dignity of a nobleman. All the most essential occupations are assigned a place in the universal system.

I took these photos outside the cathedrals. All these beings represent worldly life. But the cathedral builders, Aquinas, and Vincent of Beauvais didn’t want us to stop there. People in the 13th century linked the beings in the universe with metaphysical ideas that you have to climb higher to reach.

Gothic cathedrals and basilicas gave working stiffs like us an honored place on their outer walls. But folks in the 13th century conceived occupations in a different way. They saw things, less as independent entities than modern Westerners have, and more as parts of a larger system of the universe.

These different labors were thus seen according to a mathematical system: the 12 months of the year. Each month had its characteristic work, such as sowing and harvesting.

So each side of the south portal of the Basilica of St. Denis contains six labors. But the number 12 was very sacred, and it had other meanings.

Emile Male, in his classic book, The Gothic Image, wrote that folks in the 13th century saw symmetry as an expression of divine harmony. Thus it was no accident that there were also 12 patriarchs, 12 prophets of the Ancient Law, and 12 apostles of the New Law. 12 is the product of 3 and 4. 3 is the number of the Trinity, and Plato said that the soul has 3 components. 4 is the number of elements (earth, water, air, and fire). So 12 links the spiritual and material worlds, and the Old Testament and the New Testament. It’s thus natural that the rhythms of nature’s months and humanity’s labors echo this divine order. All domains reflect each other.

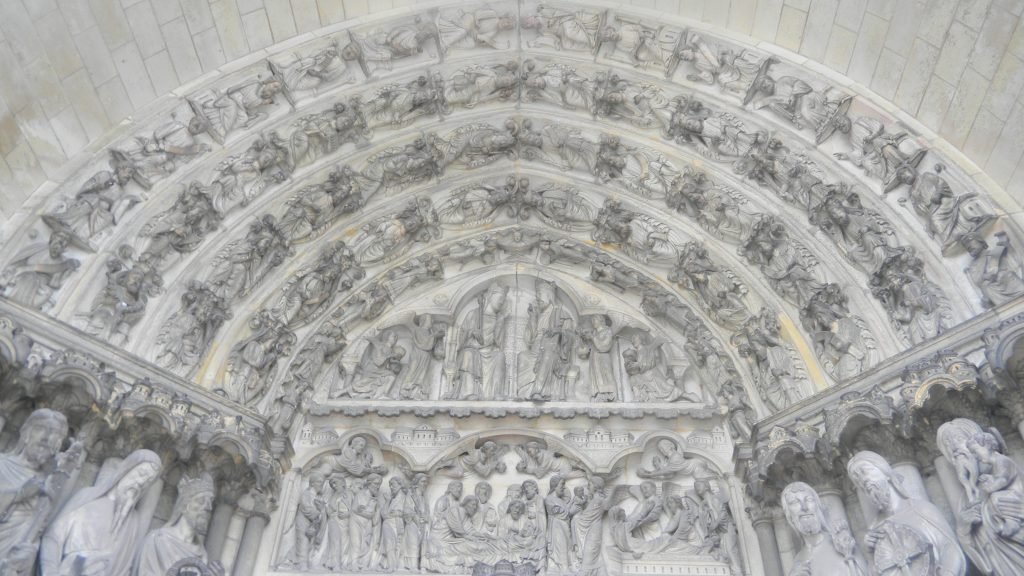

Male wrote that medieval folks found 7 to be the most captivating number. It’s the sum of 3 and 4, and it thus also unifies the spiritual and material worlds. There are 7 planets, 7 sacraments, and 7 stages of human life, and each stage has its own virtue. Universities taught the 7 liberal arts. Cathedral makers personified the virtues and liberal arts and sculpted them over the entrances (like at Rheims above, where you can see three paired rows of beings forming an arch over the narrative scenes; more paired rows of personifications hover over the entrances below). There were also 7 tones in the Gregorian musical scale.

Medieval scholars found all sorts of numerical values in the Bible. Gideon traveled with 300 companions because ancient Greeks wrote 300 as the letter tau (T). Since the letter T is in the form of the cross, Gideon prefigured the life of Jesus. Many other Old Testament stories did too.

All those sets of 7 mirrored the 7 days of creation which the Bible describes. We thus see a beautiful example of a matching set of 7 figures over Laon Cathedral’s main entrance (in the outer set above).

Nine was another especially sacred number. It’s not only 3 squared; it’s also the number of types of heavenly beings. The first photos here are of monstrous creatures in the bottom levels of God’s hierarchy of creation. Medieval folks also imagined many levels above us in a spiritual hierarchy: Seraphim, Cherubim, Thrones, Dominions, Virtues, Principalities, Powers, Archangels, and Angels.

The above shot brings us from the lower beasts outside of Rouen Cathedral to the divine order inside of it. The Gothic cathedral expressed ideas of a sacred order in which all the diverse beings exist. This order is characteristically Western by being symmetrical and linear. As you can see in Gothic logic, the segments in cathedrals like Rouen are logically related, and they proceed in a line towards Christ.

Art that Cambodians and Indians made at the same time didn’t stress this much linearity and logical clarity. Their art reflected the exuberance of their tropical climates and ancient traditions of venerating gods in the sky and the fertility of the earth. The Gothic cathedral builders also represented a holistic and spiritual universe, but they used thought patterns well established in the ancient West to order it.

This is an inspiring aspect of cultural studies–you can see patterns from cultures’ ancient pasts, and they take on new variations as times change. When you compare different cultures, they shine on each other as gloriously as Gothic stained glass windows. The heavenly beauty that their builders dreamed of is right here in the world.