Ancient Egypt was more than pyramids. I found the little things under the surface as impressive.

By the time kings were building the great pyramids around in the mid-third millennium BCE, artists sculpted and painted people in families showing each other affection. Husbands and wives drape an elegant arm around each other and look forward with contented expressions.

And no DVD and potato chips! People did like their beer though. A man wrote that kissing his wife made him feel drunk without the spuds. Children sometimes hold their parents’ legs.

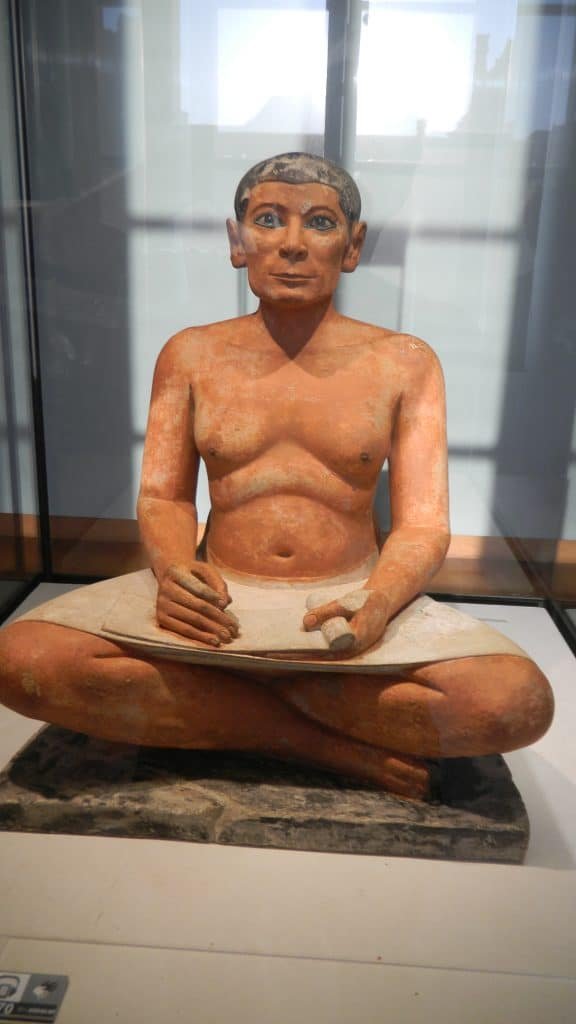

Several realistic sculptures were made of scribes.

This gentleman looks as proud and alert as we would expect an intellectually prestigious official to be.

Minoans fashioned images that were as life-affirming around 1500 BCE, but they were influenced by Egyptian art that was already 1,000 years old. After their world collapsed, Greeks didn’t attain comparable levels of humanity in their art until the Homeric texts were composed, from 800 to 650 BCE. Why was Egypt special in this regard?

Egypt was already ancient when the pyramids were built–people gathered in villages and then towns along the Nile for more than 2,000 years, and they had to cooperate to take maximum advantage of the Nile’s flooding every year.

These mores were expressed in new media when Egypt organized into a large kingdom that was unified by a royal court and writing:

1. By the Fifth Dynasty, wisdom literature emerged. Texts encouraged people to respect others, speak softly, and avoid gluttony and drunkenness. Wisdom literature became widespread in the Middle East, and the Old Testament’s Book of Proverbs is in this tradition. Both contain aphorisms about proper conduct (the Book of Wisdom expands this simple form into long passages about the importance of knowledge of Yahweh). Egyptian families today still stress the importance of being quiet and respectful.

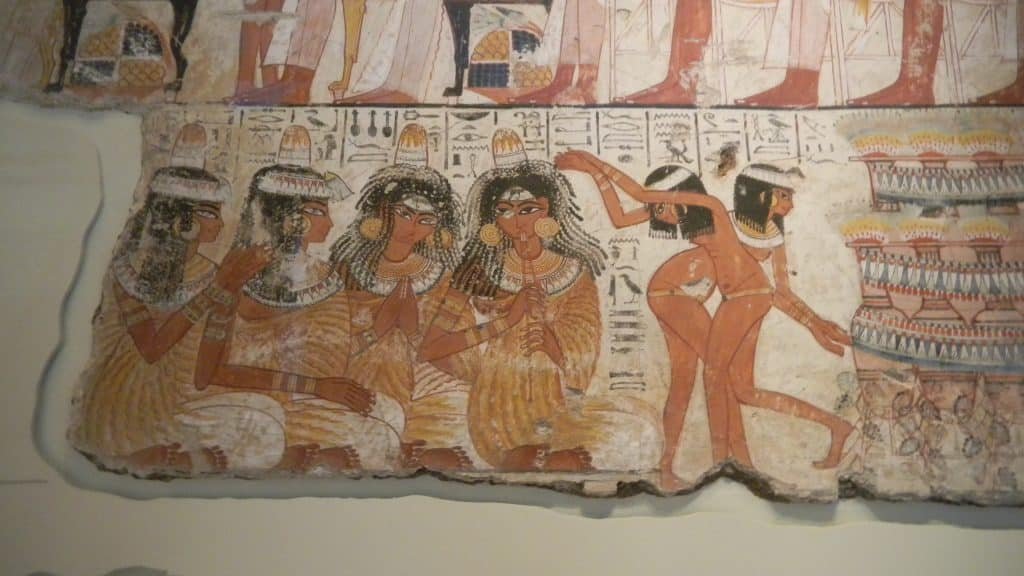

2. Painting and sculpture became more realistic in the third and fourth dynasties, and people in the upper levels of the state’s hierarchy were shown enjoying comfortable and quiet lives with their families. People enjoy lots of food and fineries, but they’re restrained and elegant to an extent that rivaled Classical Greece’s ideals.

By the time that the pyramids were built, scribes were outlining the importance of proportion. Artisans used a grid for the standing human body that had 18 squares. But their renditions of people were anything but cold. Though the sphinx in the above picture is in the guise of the Eighteenth Dynasty queen, Hatshepsut, it follows conventions set during the Fourth Dynasty, around 2500 BCE. The face is rounded in a way that makes it both strong and gentle. This became an ideal for representing the monarch in the Old Kingdom and New Kingdom. The ruler embodies Ma’at, the sacred order that the universe and the state depend on. This order is portrayed as beautiful and soft.

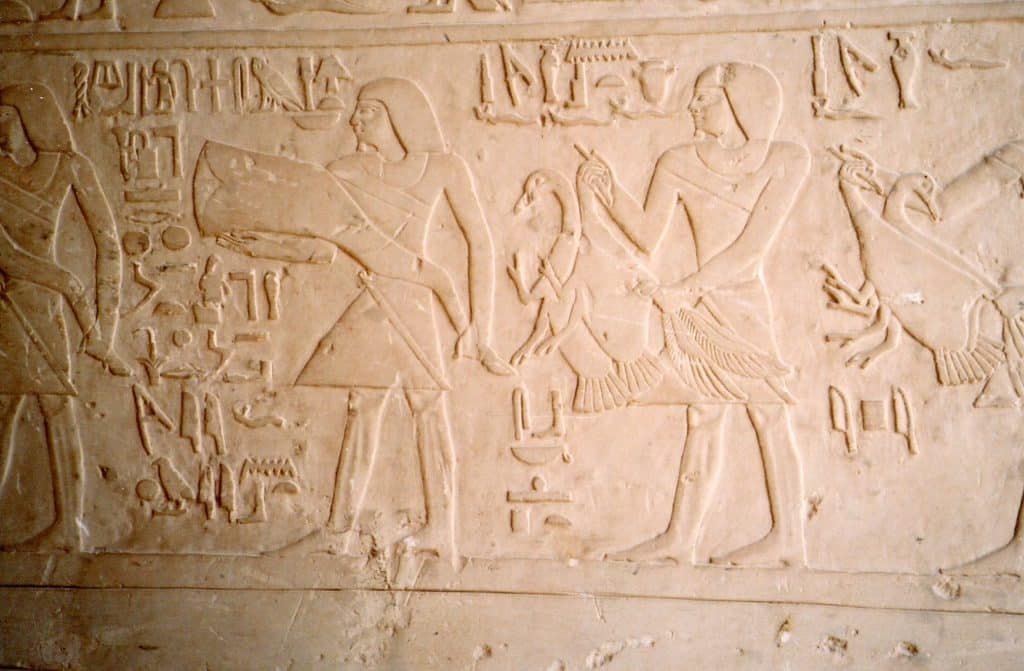

Above, we see these softened forms in the birds’ bodies that are carried for a departed elite at Saqqara during the Old Kingdom. You can see equal elegance in the people’s gaits and in the symmetry of their spacing. The procession carries food for the soul in the afterlife, but it’s conducted with refinement that transcends the narrative. Everything has a symmetry that embodies Ma’at.

The false door at the center of tombs also treated symmetry in a spiritual way. A stone rendition of a door was the tomb’s focal point. It carried an offering table scene and the name and titles of the tomb-owner. Owners also used them for brief statements about their moral worthiness. One man wrote, “I spoke truly, I did right. I spoke fairly, I repeated fairly.” The words have the symmetry of carvings.

One more ingredient helped unify Egypt: hieroglyphs. They still enchant people all over the world.

Sumeria (an equally ancient civilization, in modern Iraq) also created a writing system, but Egypt’s has a magic that still captivates people. What is it?

We have some clues in the above photo from the temple of Amun-Re at Karnak. The three symbols that are repeated emblazon lots of temples, tomb walls and texts on papyrus rolls. The cross with the loop on top was called Ankh, and it embodied the force of life. The crooked staff to its left stood for Was, which meant well-being. The pillar to the Ankh’s right, with the rings at the top, symbolized djet, which meant eternity.

All three composed a dream team of what ancient Egyptians aspired for. These symbols are often repeated many times in hieroglyphic writings. They were often used in magical formulas, which priests chanted.

Beauty was a key aspect of these formulas. The hieroglyphs in the photo are finely proportioned. Their spacing is equally elegant. Back in the day, they were painted in bright colors.

Above, we see the djet symbol repeated by the court where King Djoser conducted the Sed festival. This rite boosted the ruler’s sacred power after 30 years of rule.

Images’ symmetry helped enable magical potency to promote this statewide wellness. Temple artists learned a series of proportions and interrelations to produce scenes and hieroglyphs that represented a world that was idealized and eternal. According to Stephen Quirke, in The Cult of Ra; Sun-Worship in Ancient Egypt, a correctly proportioned image that was ritually created became a permanence (mnw, from the word mn, which meant to remain or endure). The Egyptologist Jan Assmann also noted that permanence was a central concept for ancient Egyptians, and that djet also had this meaning.

People likely believed that images’ proportions strengthened the world’s order through sympathetic magic. The Egyptologist Ogdon Goelet wrote that word, image, and the portrayed object were unified in Egyptian thought. According to the Egyptologist David P. Silverman, heka (divine energy and magic) and hu (divine pronouncement) enabled the creation of the universe, and they still empower it. Correctly fashioned hieroglyphs and other images were believed to structure them to maintain the beautiful world that Egyptian artists imagined.

So Egyptian hieroglyphs don’t just describe a world of beauty and order which people hoped would last forever. They help structure ensure its creation and ensure its maintenance. Beauty was power in ancient Egypt.

These hieroglyphs became a sacred court tradition that lasted for more than 3,000 years. Ancient Egypt did have other writing systems, which were more mundane. But scribes learned hieroglyphs as the eternal order of things, and they never deviated from it.

Egyptian hieroglyphs expressed and created a world of harmony and tolerance. Their forms still work magic all around the world–I met many people in who wanted to go to Egypt.

Egypt’s ancient art forms can help guide people today. Balanced perspectives, rather then extreme opinions, are needed in democracies. The harmony of the whole, rather political factions and cronyism, is a great ideal for the state and the ecology. Humanistic portrayals of people, instead of reductions of humans to data, can encourage more compassion. Egypt’s past can help people build a prosperous and equitable future. We all need this ancient land’s secret sauce as much as ever.