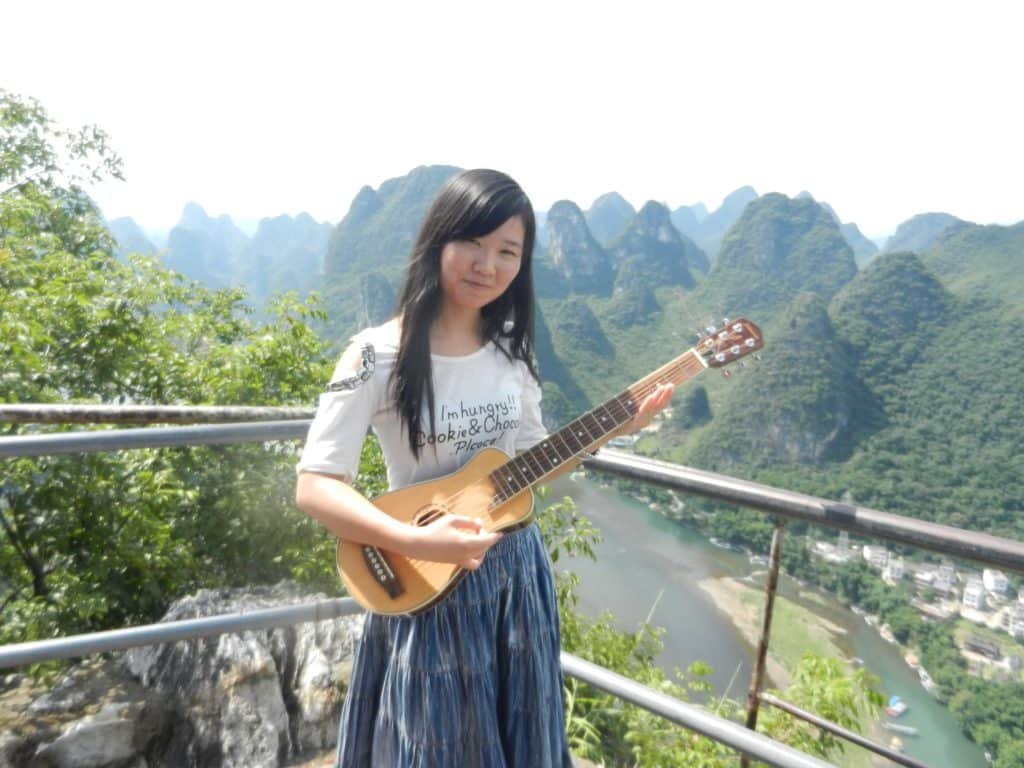

If you play a portable musical instrument, carry it as meticulously as your passport if you travel in China.

Strangers often sat with me to listen. The guy above and a friend stopped and asked to be photographed with me while I was jamming in Hangzhou. But I found that people in China listen in ways that reflect their ancient cultural wealth.

My playing style and their expectations about music differ, and we had some great intercultural exchanges.

My playing has an American approach. I often think of a statement by Jimi Hendrix that what goes on “between the notes” matters the most. It’s still crucial to know the notes. A rock guitar teacher wrote that you have to learn the rules before you break them. But I often play in between–I usually obey the rules, but add jazz chords and different notes than what’s in the current scale. Most of the best classic rock, jazz, blues, country, and funk musicians take this approach–expressing your individual feelings and personality is what music is about. But the people I met in China listened with different concepts of music.

While playing in a small park in Zhengzhou (a city with a history that goes back to the Shang Dynasty), a teenage girl sat by me and listened through five or six songs. She said, “It’s different. Does your guitar play scales?” I plucked some to show her that it does. I found that Chinese listen more for what’s collective and established. They often use music to relate to other people and feel in harmony with society. This way of listening was established in ancient times. They don’t have as many traditions of expressing what’s individual and beyond conventions as Americans do.

But things are changing in China. Almost everyone seemed to enjoy my music. My playing isn’t out there; I keep it close enough to conventions to sound warm.

So lots of young people praised me for my own songs and my solos over well-known tunes. Many youths in China’s cities are curious about the rest of the world, and my audiences liked to hear music from another continent, but while keeping one ear aimed at their own traditions.

Beijing’s Summer Palace sparkled on the clear June day. But the music I began to hear made it even more magical.

Several female voices in angelic harmonies breezed through the pavilions and greenery. Was I at the gates of Heaven?

I followed the sound and found this group of elderly women singing in a pavilion’s shade. They noticed the guitar I was carrying and invited me to join them.

I was more than happy to, but I didn’t know any of the songs they were singing. They were all Western, but most were ballads from the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century. They might have expected me to know the American songs that they sang, but I didn’t have the heart to say that they were from long before my generation. So I improvised melodies over them and tried to make as few messes as possible.

I must have fouled the air they had sweetened with plenty of errant notes. But they always made me feel welcome. One even got up and danced to a slow jazz song I had written.

When I played guitar in public places in China, young people often approached and sat down to listen. Several who played basic guitar asked for a lesson.

Bongo drums are also popular. I saw stores in several provinces selling them, and folks have a good time with each other by beating them together. They’re easier to play than a guitar, so more can make music in a group. A young woman heard me play a bongo drum and requested a lesson, and her studiousness impressed me. Before we started hitting the skin, I spent several minutes explaining percussion theory, and she listened attentively. I then described some of the mechanics of drumming, saying that they’re mostly in the wrists. I wondered if she would become bored with all the pre-bashing talk, but she kept asking more questions. After showing her some basic rhythms to practice, I started to eat lunch. She remained next to me and kept practicing. I finally had to stop the lesson when she said that her wrists were beginning to hurt. I told her that musicians should immediately rest when they begin to feel pain, otherwise they can get RSI, which can be excruciating and crippling.

Later in Lijiang, Yunnan, I had to stop a guitar lesson when another young woman said that she was beginning to feel discomfort in her wrists. I found that a lot of people in China deeply appreciate music, and it was always a joy to teach them because they were such eager students.

While walking through a crowded Beijing park one evening, I stopped to watch three locals play bongos. One immediately pointed to my guitar and asked me to join them. After we played a few songs they invited me to dinner. We walked a few blocks to a favorite restaurant of theirs. The room was only about 600 to 700 square feet, and we could barely squeeze around the one table that had a little open space. After enjoying the copious amounts of food in the cozy crowd, they said that they wanted to take me to another place without telling me what or where it was. They bought some roasted chestnuts, we hopped into one of their cars, and drove for about 30 minutes until we reached another restaurant. This one was much larger and we seemed to be the only customers. We carried our instruments inside, went into an upstairs room, and sat around a low wooden table. One dumped the chestnuts onto it, and we played in the quieter surroundings.

I played a song that I had written, which was classic rock in style but with some unusual chords for that genre. She swayed to the rhythm, and when I finished, one of the women asked me if I wrote it. I had never mentioned composing music to any of them, so I wondered how she got that idea. It seemed that she saw compatibility between the music and something she read in me.

The city of Kaifeng was high on my list of places to visit on this last trip through China.

It presided as the capital of the Northern Song Dynasty.

Tribes from the north called Jurchens sacked it in 1127 and forced the royal court to move south to Hangzhou. Since then, the Yellow River flooded Kaifeng several times. But the modern government has tried to recreate some of the Song Dynasty’s atmosphere in its 11th-and 12th-century glory days. After dinner, I carried my travel guitar through a public park by a lake with several pagodas around the shore.

Two elderly male erhu (a two-stringed bowed instrument) players invited me to sit and perform with them. They then asked me to come back the next evening. When I arrived, a traditional folk singer was with them. Middle-aged and about five-foot-ten, she had a big and lush voice. I sat next to her and improvised as she performed. Hearing her up close while savoring the pagodas’ silhouettes against the setting sun felt like a deep immersion in the Song Dynasty’s cultural life.

She then asked me to sing and handed over the microphone. I said that I don’t sing well but she kept insisting. The only songs I have experience singing are classic rock, so I chose a ballad by Jimi Hendrix called “The Wind Cries Mary.” A spacey hippie tune thus wafted over the waters in what used to be China’s cultural capital. But the song’s music is slow and wistful, so it mixed with the pagodas, indigo waters, and sunset into an ethereal atmosphere. Combining reading about China with appreciating music from many times and places enabled me to enjoy an immensely meaningful field that made me feel profoundly connected with people in several cultures. Hendrix’s music can blend with Chinese traditions to create magic. I’m a Qufu child.

All these groups of people inherited and have preserved ancient assumptions that music essentially resonates throughout society. No argument from me, since I still treasure the memories of all of them.