INTRODUCTION

I thought I found heaven on earth during a round-the-world trip back in 2007, even though the world has been hellish for so many people. The variety of cultures that I explored on that journey (in Southeast Asia, East Africa, and the Middle East) showed me a way to think about our planet which schools don’t typically teach. The diversity of societies’ ways of thinking showed me that most of us learn only a sliver of our potentials for well-being. Before leaving for those places, I studied them as deeply as I could, and that made my adventure so enjoyable that the most apt description of it was “paradise on earth.”

But since that trip, ecological destruction has worsened, America’s and many other countries’ politics have become more divisive, gaps between the rich and poor have widened in many nations, a pandemic has been raging around the globe, and several countries are building hypersonic nuclear missiles that will be able to cross an ocean in less than 30 minutes.1 How can a person who talks about heaven on earth not be as kooky as a squirrel on meth?

But my travels and studies have shown me that this question is based on a perspective that comes from looking in the wrong direction. These problems began with views of the world that were narrow and fragmented to begin with. Back in the 1970s, the physicist and systems theorist Fritjof Capra wrote a book called The Turning Point, which warned that humanity was polluting the planet so much that its consumerist lifestyles and international political rivalries were unsustainable. He condensed our problems into three words: a crisis of perception—people see the part more than the whole. Corporations and authoritarian governments have spewed carbon, sulfur, and methane into the atmosphere, hacked down rainforests, and dumped cancer-causing chemicals into rivers with the myopia of a toddler wetting his own bed.

On the heels of the 1970s, deregulations during Ronald Reagan’s administration, increasing corporate control of America’s economy and politics, and an explosion of dumbed-down pop culture followed. The Federal Communications Commission deregulated television so that slogans, fragmentary images, and extreme political messages increasingly pervaded the country. The right-wing religious extremism of Jerry Falwell and R. J. Rushdoony grew into a nationwide movement.2 At the same time, many of America’s schools failed to give students big perspectives that included histories, cultural nuances, and ecological implications. In the late 1980s, a survey of college freshmen found that most did not know when World War Two, World War One, and the American Civil War occurred. Haynes Johnson’s book Sleepwalking Through History details this convergence of perspectives that combined materialism, greed, and right-wing religious extremism.

Timothy Snyder, in Road to Unfreedom, wrote about the loss of newspapers with full-time reporters and editors who verify facts. Today many towns and cities across America lack a credible news source with professional standards of objectivity. Residents have instead often relied on talk radio and social media groups that place their political biases over larger and more inclusive perspectives.

Hedrick Smith, in Who Stole the American Dream?, chronicled the increasing power that corporate lobbyists have wielded in Washington, D.C. since the early 1970s, and Niall Ferguson, in The Ascent of Money; A Financial History of the World, detailed the rising dominance of finance in the world. Both trends have often converged into cramped perspectives that place short-term profits over the ecology, culture, and people’s full humanity.

We need radically new thinking that is much more encompassing, and which sees the whole as primary. We’re saddled with our earth-in-the-balance problems because this whole hasn’t been appreciated to the extent of becoming prominent enough in our perspectives to guide political policies and personal choices. People have brought the world to the brink of several catastrophes because they’ve lacked holistic views of it and have often focused on narrow visions of money, status, and consumerism.

But what is this whole? How big is it, and how inspiring can it be? What ways of thinking can enable us to appreciate it as fully as possible?

Since there are thousands more cultures than most people have been taught to appreciate (the Canadian anthropologist Wade Davis has calculated about 14,000), the world’s ecology of societies and ideas enables us to be godlike by being able to mentally fly at will to any place, savor its cultural wealth, synthesize ever larger perspectives, and share them with others to nurture ever more creative and compassionate societies. The educational resources to make the world heavenly are already here, but most schools teach little about them and corporate media occlude people’s views of them.

The philosopher Alfred North Whitehead wrote that the European philosophical tradition, which America has inherited, is mainly a series of footnotes to Plato. Although people now have access to societies all over the world, most largely think with ideas that were established 2,400 years ago. My travels gave me a model for a newer, bigger, and more inclusive way to see our field of connections, which puts all cultures on an equal footing so that we can deeply enjoy them and synthesize them into higher levels of creativity. Perspectives from these heights can help us cooperate globally, think holistically and flexibly to keep our planet livable, and build societies that can enable their majorities to reach their full potentials for well-being.

Perspectives that my round-the-world trip and later journeys gave me were on a different scale than any convention I learned in school. Seeing so many unique cultures in succession was much richer than the experience of traveling to a different place, expanding mental horizons to its society’s thought, and calling it ultimate truth. The experience was of a continuous expansion so that an increasing number of places reflected each other. It’s common to say “think bigger” without really appreciating what “bigger” really means. The term is often used in relation to conventions, as the next step ahead. This keeps us largely bound to the same perspectives and concepts. Instead, we can repeatedly soar beyond our current perspectives and concepts with the ease and joy of a god as we deftly explore one culture after another.

My previous book, Thinking in a New Light, offers a simple way to savor and synthesize different cultures so that we can free ourselves from one system of ideas and reach our full potentials for big thinking. This book does the same, but with other places’ traditions. More than half of the first book focuses on Southeast Asia because most people have had little exposure to its cultural depths, and I fell in love with the region’s beauty and diversity. It was exhilarating to be immersed in seemingly exotic ways of thinking, feel at home in them, and realize that they’re as rich as the Western philosophical tradition. Most of my prior book compared that region with Western conventions and showed how to synthesize any perspectives so that thinking becomes a dance all over the world, which revels in all societies’ traditions. The first half of this book travels to ancient Greece and ancient India (which together have greatly influenced the thinking of more than half the world’s population) and compares them. In the mid-first millennium BCE, thinkers in both areas asked a question that the Mundaka Upanishad succinctly posed: Through what, when known, does all become known? Thoughtful people in Athens, Western Turkey, and Southern Italy were also seeking the ultimate principles of the universe, which can give people the most comprehensive knowledge of it. We’ll journey through these ancient Indian and Western cultural landscapes and appreciate how the societies and their natural environments encouraged different questions and answers. We’ll then explore several other cultures’ ways of thinking about the world, including African and Chinese. Our journey will enable us to achieve greater independence from any society’s conventions and blend more ideas into views of the world which are so big that we can leap from region to region at will, push the boundaries of human experience off the scales, and enjoy perspectives that no culture’s mainstream has yet known.

Leaping as easily as a Greek god can inspire us to behave more like highly evolved souls than predatory animals. We can transcend conventional mental limits, choose the concepts we think with, blend them in ever more ways, and enjoy conceptual breakthroughs whenever we want. We can also become godlike in a sense that Christians, Hindus, Buddhists, Muslims, and Jews have honored. By understanding all people more fully, we can develop more compassion for all and deepen love for them.

In the 17th century, Rene Descartes concluded, “I think, therefore I am.” But a mystic who practiced yoga from Indian traditions thought that he had it backwards; the sequence of ideas should flow in the opposite direction: “I am, therefore I think.” India’s spiritual heritage, dense extended family networks, and vibrant natural landscapes which envelope communities in searing heat and pounding monsoons have often encouraged people to assume that embeddedness in the environment is more primary than a single ego that’s differentiated from it. A self is immersed in an abundant web of spiritual energies, personal relationships, and natural phenomena. So what is your starting point when thinking of the basis of a person’s existence? Is it the individual’s integrity as a unique thinking subject? Is it the whole environment? It depends on the assumptions you start with, and different cultures encourage diverse initial perspectives and fundamental ideas.

Other cultures have shown even more ways to think of the person’s source of being. Traditional societies throughout sub-Saharan Africa have often treated the community as the basis of reality so that many people there have been inclined to change Descartes’ statement to “I belong, therefore I am.” The Nguni word ubuntu has sometimes been translated into English as, “We are, therefore I am.” In Africa’s challenging lands, with few long and permanently navigable rivers, many disease-carrying insects that have limited the numbers of beasts of burden, and predatory animals that can crush a lone traveler’s bones to the marrow, people have traditionally seen the community as the basis of well-being.

So one of the main questions that philosophy began with (What is it, which once known, makes all things known?) provokes the deeper question, Who wants to know? And this provokes the even deeper question, How is this who constituted? Different cultures have held different dominant assumptions about what a person is, the source of a person’s identity, what is most important to know, and how to acquire that knowledge.

When we consider the world’s variety of cultures, thinking can expand from one question to an examination of why that question has been considered fundamental, and to explorations of assumptions that other societies have held. In Thinking in a New Light, I called this expansion looking At,With, and Beyond. We can combine:

- Looking At (perceiving and thinking about a thing or environment according to your culture’s conventions),

- Looking With (examining why your culture has emphasized those conventions), and

- Looking Beyond (exploring other cultures’ conventions).

This deceptively simple extension of thinking, if repeated so that it includes more and more cultures, can enable us to regularly gain new perspectives, synthesize more ideas, enjoy more types of beauty, deepen empathy with more people, and savor the infinite abundance in societies, people, and natural landscapes. We can more fully appreciate our planet and all the beings we share it with rather than shoehorn it into one system of categories and reduce it to means for making money. Thought in today’s global civilization can now be updated to, “I think, therefore I love.”

The first country I visited after Southeast Asia (Mauritius) is an excellent place to begin looking At, With, and Beyond. It’s small, remote, and not well known. But folks from many cultures have settled there, and it thus showed me that even a little island that most don’t think about can be a launching pad for one perspective of the richness of our planet and ourselves after another.

Mauritius is on the other side of the world from my home in California. It’s about 500 miles east of Madagascar, and its population includes people whose ancestors came from India, Continental Africa, Europe, the Middle East, and China. I was curious about this country’s eclectic cultural landscape. Since California is also known for ethnic variety, I felt both kinship with and curiosity about the most distant inhabited place in the world from my home.

I instantly liked the Mauritians waiting at the gate in Kuala Lumpur’s airport. They clustered in small families, and all spoke in soft voices. Many gently tended their children. My only worry was they all spoke French, and as a West Coast boy, I wasn’t used to hearing it. I had read that people throughout the island can use English, but they prefer the more musical tongue. That made sense to me because the language’s soft cadences and poetic ambiguities mix well with Mauritians’ suavity. It can express many of their feelings. People there often speak English in business settings. Whether I would mangle French beyond recognition or blurt out American English, I felt that my tongue would be two left feet.

I hoped that wouldn’t limit my ability to relate to the locals, because Mauritians value intimacy. A code of conduct in a tourists’ guidebook said that it’s okay to lounge on the beaches, but the people will bare their souls to anyone interested in speaking with them.

The soul baring began as soon as the plane took off. The man next to me was about sixty, tall, thin, and ethnically Indian. The aircraft had sat at the gate for 30 minutes after the scheduled departure time. He fumed over a government official boarding just before we left and figured that the pilot had waited for her. He asked the stewardess and she confirmed his suspicion. He turned to me and said, “You see! I knew it was that woman getting preferential treatment! This happens too much in Mauritius!”

He sloshed back several little glasses of wine and whiskey after take-off and chattered nonstop. He warned me that Mauritius is not the congenial mixture of cultures that I had read about. It’s strictly divided into different ethnic communities. Hindus are the most numerous (with 49% of the population) and they’re much wealthier than black people on average, so they have often dominated politics. The government tries to please them and has often let Blacks struggle. “We are always walking on eggshells.” He griped about political divisiveness so much that I couldn’t tell whether he was being objective or indulging in an alcohol-fueled rant.

So I received two contrary descriptions of Mauritius before arriving. Several books praised its friendliness and tolerance, but this man emphasized its ethnic clashes. As a business professor at the University of Mauritius, he was well educated, so I had to give his opinion weight.

The island looked heavenly enough from my window. Rolling carpets of light green sugar cane fields alternated with jagged mountains, and the sparkling ocean surrounded all landforms. It seemed like a pristine Hawaii before its 1960s tourism boom.

Sega music leaped through the speakers as soon as we landed. This is a polyrhythmic style of singing which was developed by slaves and their descendants many generations ago. Some newer performers have mixed it with reggae and created a style called seggae. Many songs rail about social injustice and others celebrate good times, but all can make you want to flex every joint in your body. My lively seat mate, the views from the plane, the jubilant singers, and the bursting rhythms mixed into a pulsating introduction to the country.

The beats continued when a customs official asked me to open my bags. “Why do you have so many books?”

“I’ve been traveling in Thailand and Cambodia, and I bought them there.”

“Why don’t you buy electronic books?”

We discussed the merits of printed and e-books, and agreed that physical books can make readers feel more engaged with the content. I had never had a philosophic chat with a customs official before. Most strictly focused on doing their duty and avoided projecting their personalities. This man and the business professor confirmed that human interaction is paramount in Mauritius. I was sure that I was going to like the place no matter what the business professor had said.

The taxi ride to my hotel was about 40 miles over winding roads that shimmied through sugar cane fields. Steep serrated mountains towered beyond the dense masses of stalks, and many slopes rose at 70-degree angles. Their dark blue-green hues contrasted with the cheerful light green that enveloped us. They seemed to stand as sentinels around the joyful verdant growth. The island emerged from huge underwater volcanic eruptions millions of years ago, and it rises directly from the Indian Ocean’s floor. I thus saw many contrasts between craggy peaks and well-nourished soils with cane swaying in the breezes. Even the land dances.

We were heading for a small town on the southwestern coast, called Tamarin. The Southwest is the least affected by tourism. Farther north up the coast is Port Louis, the capital and the island’s largest city, with about 150,000 souls. The resorts are mostly concentrated around the northern end. Mine was the only one in Tamarin. The quiet two-lane road from the airport made me look forward to a more authentic introduction to the country.

After dinner I strolled across the road to the beach and waded into the water. No one else was around. I looked up at the flickering stars and savored the idea of being on the other side of the world. Some of my fondest boyhood memories are of walking on Californian beaches with my dad. We gazed outwards and discussed distant lands and past times. I was now as far as possible from where we stood without going into space, as though our explorations were climaxing. I would find that Mauritius can satisfy any wide-eyed child’s imagination.

My first morning there already showed that this little island has many sides. It began beautifully. I climbed into a rickety old bus that chugged up to Port Louis. We rode through verdant countryside and small, intimate towns. The homes were painted in soft yellows, pinks, greens, and baby blues, and most were single story and flat roofed. Trees and thick shrubs surrounded them with greenery. All the life-affirming colors whirled as we rode by. The other people on the bus were young Black Mauritians, and they were as soft-spoken as the folks at the gate in Kuala Lumpur’s airport. The civility and welcoming surroundings made me think that people don’t need much money to be happy on the island.

But Port Louis sometimes showed a stern face. I took a taxi from the bus stop to the harbor, which boasted a new shopping arcade in a long newly constructed brick building. It was spiffy but antiseptic, like most American malls. A slick intercity highway streaked next to the harbor, and a walkway tunneled under the road. When I exited on the other side, I was in the city’s center. It bustled with Blacks, Indians, and Middle Easterners, but everyone looked deadpan serious. The natural surroundings were enchanting because the town sits between the ocean and jagged mountains, but the people were all business—few smiled. Why?

The city has several sections within easy walking distance from each other. There’s a small downtown with a few modern skyscrapers that rise about 20 floors, so they’re not tall enough to block views of the mountains or cast dreary shadows on the streets. A long, straight park stretches through its center, but the people sitting on the benches looked more serious than I’d expect in a recreational zone.

I thought the district just north would be more fun because it was full of little mom and pop shops which combined into a feast of colors and flavors. Displays of produce in every shade of green, red, and yellow glinted next to little clothing stores, restaurants, and candy shops. But few people within sight smiled, so the whole town felt jarring after my first experiences in Mauritius. Several days later I told a woman in Tamarin that few smiled in Port Louis, and she said, “People up there are too busy to smile.”

A little east of the shopping district is the city’s main mosque, which was built in the mid-19th century in a fusion of Arabic, Indian, and Creole architecture, and a small Chinatown spreads next to it. The latter wasn’t as lively as I expected. Its center was mainly a cluster of restaurants and little grocery stores. The Chinese in Mauritius are known for keeping a low profile. Many came from Hakka-speaking regions on China’s southeastern coast in the 1940s to escape the ravages of World War Two and the fighting between Maoists and Chiang Kai Shek. Many have lived quietly as merchants, and some have recently become IT professionals. With few people outdoors, Chinatown felt like a quiet suburb.

After eating lunch in one of its restaurants, I walked inland and was outside of Chinatown within a few blocks. The streets inclined slightly, and the neighborhood was clean and cozy. Two-story duplex homes in soft whites, greens, and yellows lined the narrow road I walked on, and many had French balconies with ornate black wrought iron railings. The area looked homey and I greatly enjoyed the quick succession of Islamic, Chinese, and French architectural styles, but I still didn’t see any smiles.

I continued up to a dark grey stone fort that haughtily presides about 250 feet above the town. The British built it when they ruled, and it’s the best easily accessible place for a bird’s eye view of Port Louis. The scenery was spectacular. Downtown was on my left, and its skyscrapers sparkled in front of the mountains. The ocean spread in front of me, and cumulus clouds tumbled over it as playfully as dolphins. Tree-lined residential areas rambled on my right, and more rugged peaks thrust behind me. All aspects of the natural and human landscape were in scale with each other and varied enough to seem as though they were dancing.

But a short and portly black female guide in her fifties approached me and described a more divisive society. Most people lived in their own ethnic group’s section. A lot of Muslims and Chinese reside around Chinatown. Hindus live in the wooded northern area. Blacks and Creoles are crammed into the foothills behind us. You can recognize their neighborhood because a large percentage of their houses are unpainted—they can’t afford the paint. The city suddenly seemed full of narrow mentalities that fell short of the surroundings which mixed so many different cultures and natural landscapes.

The anthropologist Thomas Hylland Eriksen, in Common Denominators; Ethnicity, Nation-Building and Compromise in Mauritius, saw many ways in which different ethnic groups in Mauritius are divisive. Managers prefer to hire people from their own because they trust them more. Although younger folks increasingly marry outside their cultures, many parents frown on it. Some Indian elders ask, “Why can’t you find a nice Hindu girl?”

But Eriksen also saw several ways in which cultures have recently been mingling. Young people dance together in nightclubs. Most families own TVs and watch many of the same shows. The education system is standardized, although not all ethnic groups have equal say about the curricula.

So the country is in a dynamic period. Old prejudices linger, yet people share a multiethnic landscape with richness that rivals the land’s beauty. But the island’s recent history suggests that there’s a lot of inertia to overcome.

The divisiveness I saw in Port Louis reflected some of the country’s past. Europeans used to rule Mauritius, and they created a plantation economy. The place has thus been burdened with a legacy of rifts between a few wealthy families and poor laborers.

Arabian traders discovered the island in the Middle Ages, and Portuguese landed there in the early 16th century, but neither stayed permanently. The Dutch were the first to settle. They named it after Prince Maurice of Orange, who led their revolt against Hapsburg Spain in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. They introduced sugarcane and began to import slaves from Madagascar and Java. But they focused more on larger and more lucrative places like Indonesia, and abandoned the island in 1710.

The French followed and renamed the place Isle de France. They developed it more by building Port Louis and a network of roads. But the system of plantations with a small circle of elites over slaves toiling in the fields was strengthened.

Enter the British. They took over in 1810, during the Napoleonic wars. They allowed the French plantation owners to keep their holdings and language, and liberated the slaves after England’s parliament passed the Slavery Abolition Act in 1833. Many former serfs built ramshackle houses in places no one else wanted. More sugar refineries were constructed, and Indian immigrants provided most of the labor. Visitors on the island found them living in crowded shacks with dirt floors. Gandhi was appalled by their plight when he went there in 1901; more than 300,000 sweltered under the beating sun.

So baggage from a long-established plantation system has retarded cultures’ mutual appreciation. People became used to being divided in a hierarchy with Whites on top sipping cognac on their breezy verandas, Muslims and Asians as respected merchants and middlemen, and a majority of Blacks, Creoles, and most Indians grinding out meager livings on the bottom.

The country’s economy and living standards have improved greatly since Mauritius became independent in 1968. In the 1980s the World Bank called Mauritius an economic miracle. Textile plants, light manufacturing, and tourism were first established. The government then helped IT, finance, and other high-tech industries to propel the country into the digital age.

But many people still hold us-versus-them mentalities. Hindus have benefited the most from the economic growth, and they have often dominated the island’s politics. Many are guarded about their newly won status because they’re conscious of their former underling positions. Some Blacks and Creoles resent them and say that they’re money grubbing and devious. Some Hindus and Muslims look down on them and accuse them of being lazy and hedonistic.

But I frequently saw opportunities to transcend these vulgar ethnic stereotypes and narrow focuses on class. I hopped into a taxi back to Tamarin, and the congenial grey-haired Indian driver sped out of town and took a narrow road that corkscrewed up one of its southern hills. Rain had briefly fallen in the morning, but the clouds had scattered and the sun shone in full glory. The weather often changed quickly throughout my stay. I’d suddenly be caught in a downpour and it would immediately clear up. The untrammeled sun then blessed the freshly cleaned fields and homes so that everything glistened. Scenes changed rapidly on the island. Storm and sunshine; town and country; sugarcane fields and craggy mountains; land and ocean; and Hindu temples, Christian churches, and mosques alternated in pulsating rhythms.

I found Tamarin more relaxing to amble through than Port Louis. A few hundred single family homes speckled it. The beach was long and narrow, with many trees providing shade. Houses lined the ocean front that the resort didn’t occupy, and little boats rested bottom-up in the sand. Inland, narrow streets climbed uphill for three or four blocks to the intercity road. The town became popular with surfers from other countries in the 1970s, but this was the off season and I never saw a single person on the waves.

Two mom and pop grocery stores supplied the town with its daily needs. The bigger one occupied a corner on the intercity street, and a middle aged Chinese couple ran it. On one of the roads that descended to the beach, a thirty-something Black woman owned a tiny store no bigger than an average living room. She had the sweetest eyes and smile though her economic situation seemed humble, so I usually bought groceries from her.

Light green fields carpeted the land across the main road, and they slowly rose uphill to the base of a steep and jagged mountain. The town seemed idyllic, with a long, shady beach on one side, a majestic peak on the other, and a placid neighborhood in between. This was the easygoing Mauritius I was hoping to find.

And while there, I saw how magnificent the whole world is. The island encapsulated many of the problems with today’s narrow thinking, but it also showed ways to overcome them and develop bigger perspectives that can allow us to revel in our full humanity.

PART ONE

THE SEA AND THE FOREST

HUMANITY’S ANCIENT GREEK AND INDIAN ROOTS

CHAPTER ONE

EXPLORING THE DEEPEST SOURCES

Hindu temples in Mauritius rise from the dense sugarcane and project gods in bright reds, blues, greens, and yellows. Walking around them makes it easy to feel that these profusions of images empower the vegetal growth. They also connect this little island with the immensely vibrant cultural landscape of one of humanity’s most influential civilizations.

Westerners can find Indian temples overwhelming. Forms and gods seem to stick out in every direction. I once heard an elderly woman in Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum tell her companion, “I don’t understand Indian religion. There are too many gods.” Indian temples seem to be the opposite of a Greek temple’s clear and static geometric forms. The proportions and regularity of a Greek temple’s base, portico, roof, and lines of columns make it seem like the perfect distinct entity. It’s complete, independent, and permanent. It expresses the order that endures as everything else in the world changes. But so many images and forms project from many Indian temples that a lot of Westerners find the buildings baffling.

Copiousness has been one of the most central ideas in Indian art and thought. It’s reflected in countless temples, sculptures, paintings, festivals, fabrics, cuisines, aromas, and sounds. All project abundance that dwarfs the individual entity so that it seems engulfed in an immeasurably larger field of energy. This all-encompassing vitality has been one of the most prominent ideas in India’s history. It has had subtle metaphysical expressions and it’s also very sensual, so it allows room for all mentalities. Comparing Western traditions rooted in ancient Greece and Indian traditions has given me many of my most pleasurable experiences while exploring different cultures.

Each of the four times I visited India, something happened between the airports in Singapore and Chennai which made it clear that I was entering another world, which was especially lively. The first time (in 1995), I flew from San Francisco to Hong Kong, and then on to Singapore. So far, I was surrounded by ethnically Chinese people and Caucasian Americans. The colors, aromas, and sounds were subdued according to Confucian and classical Western balance.

I then reached the gate in Singapore and sat down, and two Indian women in their thirties soon arrived and took seats across from me. Their saris blended into a kaleidoscope of flickering golds, browns, reds, yellows, blacks, and glass inlays. Their sons played together on the floor, and the two women, who were formerly strangers, started talking about them. All at once, I saw barriers between colors and between people open up into a larger field which seemed more effervescent than any distinct entity.

A small elderly man sat next to me on the flight to Chennai during my second trip. When I opened my passport for the number to write on my arrival card, he leaned over my picture and stared at it. Every time I was about to enter India, I got a message that personal space was going to be a luxury.

After retrieving my baggage at Chennai’s airport during my first trip, I stepped out the door and into the parking lot. It was around midnight and the whole area was full of people slowly milling around in the languid air. Streetlights and cars’ headlights shone in the thick mixture of dust and smog, giving it a soft glow. From the ground to the sky, all matter seemed densely packed, but the people’s gentle bearing and the area’s shimmer made the environment feel like an all-pervasive spiritual oneness. It was equally chaotic and serene.

The day I arrived during my last trip, I took a taxi to a five-star hotel to ensure a full night’s sleep after the three international flights. Next morning I took an auto rickshaw to a school on the outskirts of town, where I would spend the rest of my visit. Auto rickshaws have two wheels in the back and one in the front, and both sides of their passenger compartments are open. I always enjoyed riding in them because nothing obstructed my views of the scenery. The drivers were often quirky men. Some gabbed, others sang, and one drove me into a military base, where I had to explain to the stern-faced guard who stopped us that I didn’t know why he brought me there. There’s never a dull moment in an auto rickshaw.

The driver motored me along a narrow, bumpy dirt road. Flat-roofed homes and shops in off-white, soft blue, and light yellow hues, which were caked with brown dust around the edges, lined both sides. Palm trees enveloped them in thick greenery. Fabric stores displayed their wares so that purples, reds, yellows, and greens glimmered. A butcher shop open to the street displayed a line of enormous sides of buffalos and pigs. The crows landing on the counter to snatch morsels made me eager to stick to a vegetarian diet. Cows, cars, trucks, and carts often clogged the road; motorbikes and pariah dogs nimbly wove between them. Two gray-haired men stood in the middle chatting, and my driver plowed between them, forcing them farther apart. One pressed his hand on the side of the vehicle and exclaimed, “Please!”

This density of life was dramatically different from the human-scale patterns I often saw in Mauritius. It seemed all-enveloping and full of energy that was too profuse to measure. This abundance which dwarfs all individuals has ancient roots, so we will venture into some of their deepest sources. We’ll compare them with some of ancient Greece’s most ancient cultural roots and find that remote antiquity profoundly influenced ways in which people from both traditions have thought ever since.

W.K.C. Guthrie, in The Greek Philosophers from Thales to Aristotle, noted that each epoch’s philosophic discussions are largely governed by assumptions that are seldom or never mentioned, let alone questioned. But noticing your own and exploring others’ assumptions (looking With and looking Beyond) is a crucial skill in a globalized world in which people in different cultures need to understand each other. It is also necessary for appreciating our whole field of connections (seeing the whole rather than the part, as Fritjof Capra wrote). We’ll begin to find how deep unquestioned assumptions are in this chapter. This will help us to explore our own and other societies’ ideas more objectively and to see infinitely beautiful cultural landscapes reflected in them. We’ll find that what seems most obvious is limitlessly abundant.

A.L. Basham, in The Wonder That Was India, wrote that many ancient Indians saw brahman as a hidden potency that pervades nature and energizes it.1 The word brahman is neuter rather than masculine or feminine. Romance languages (including Spanish, French, and Italian) differentiate masculine and feminine nouns and give them different endings. The neuter case is neither, so it’s easy to see brahman as more primary than gender-based distinctions.2 It’s the unity which the cosmos emerged from before energies differentiated into the forms and things around us, and it still exists within each.

The word brahman also means to expand, to issue forth, and the power in mantras in the Vedas, so it’s also the emanation of the universe’s energies after its initial unity. Its root, bhr, also meant to make strong and solid. Brahman is thus both the primeval unity before creation and the energies that have empowered creation. This vitality still exists in and infuses all beings. Surendranath Dasgupta, in his history of Indian philosophy, thus called brahman both transcendent and immanent.3 In contrast with ancient Greeks’ love of proportion and static forms, brahman expresses a profuse outpouring of life from a prior unity, as well as that unity’s continuing existence in all present life forms. It’s all things in the universe and also the ground of their existence. Brahman became one of India’s most influential ideas, and it underlies much of its art and thought.

Brahman unifies two ideas that many Westerners have found contradictory: unity and an enormous multitude of existences. It pertains to the entirety of creation rather than being concentrated in any single entity. Opposites are unified in this field instead of seen as distinct, as Greek temples and statues of gods and distinguished people are. The whole field is the main reality, and it’s constituted by the energies that animate all forms and things.

Yes, the religion that’s most widely followed in India (Hinduism) has many gods, but they emerged in the same field and express its enormous variety of forms and personalities. Many mystics thus say, “All the gods are One.”

Where did this focus on abundant flow of energy within a unified field come from? The natural landscape was one of its main influences. Things often seem to happen on a cosmic scale in India. While living in the school outside Chennai in 1996 (it was called Madras then), I always got up around 6:00 a.m., stepped out of the dormitory, and ambled to the showers, which were about 600 feet away. I arrived in Chennai in late summer, when temperatures skyrocketed during the day. The weather was already warm at dawn, but comfortable as long as I walked slowly. The air was still and the neighborhood was quiet. The area was rustic then; most homes had thatched roofs and dirt floors. This time, when night transitions into day so that both are equally balanced, has been considered ideal for meditating. The environment is tranquil, like the prior unity that everything differentiated from.

But it was already hotter when I finished my shower. Sweat began to drip from my temples and the back of my neck as I strolled back to the dorm. High-pitched nasal voices of female singers began to emanate from local farmers’ radios. Pariah dogs yapped and cows mooed. It felt hotter every 30 minutes.

By noon the sun blazed in full majesty. The road teamed with motorcycles, cars, donkey-pulled carts, pedestrians, bikes, cows, dogs, and goats. The aromas mixed truck exhaust, animal dung, and spices—a concoction that’s probably burned into my brain for the rest of my life. The neighborhood now bustled with all of nature’s life forms. The energy that the universe came from flowed in full abundance.

The morning thus seemed like a microcosm of creation. I was first immersed in the unity and peace before all the universe’s patterns emanated, and then became part of an infinitely profuse river of life.

Locals joked that Chennai has three seasons: hot, hotter, and hottest. But in December (during the same trip), the monsoon roared in. Sheets of rain slammed the dorm walls, and wind ripped panels off the main hall. The water quickly rose to the middle of my thighs. Wading in its cool caresses felt soothing until a groundskeeper warned me about poisonous snakes. We all finally evacuated to an apartment building on higher ground.

When the rain subsided, three other young American men and I walked out to the main road. We felt giddy after being cooped up, so we decided to ride into town for dinner. The area was now cleaned of the grime that normally gave its light colored buildings dark brown frames. A dead cow sprawled on the roadside, and a lone baby goat frantically called for its mother. But the water drops on the trees and bushes sparkled under the triumphant sun, and the area looked fresh. The cycles of nature in this ancient land had turned. The old had passed away and life was renewed.

When we reached the main road, I spotted my regular auto rickshaw driver, Surya. He was yacking with a few other drivers, and one of my companions remarked in his Alabama drawl, “Hey! Surya’s drunk!” When Surya realized what we were laughing about he exclaimed, “No! No! Surya no like drinks! Surya clear! But today, fight with wife and I’m having some feelings.” We threw caution to the wind and insisted that he drive us anyway, since auto rickshaws don’t go very fast. Surya sang and we helped him navigate—“Here comes a bus, Surya.” We all had a lot of laughs that evening. Emotional patterns in India often reflect nature’s copiousness. Many people feel fully and sometimes express themselves without as much reserve that folks from many Northern European and East Asian cultures expect.

Sanskrit has several beautiful words for free-flowing emotions. Mudita is a sympathetic joy, which you feel by delighting in other people’s joy. Prasanna means clear and bright, and it also refers to feelings of pleasure that ripple to more and more people. These positive emotions are less bound to the ego than most American and English concepts of emotion; they instead seem to extend throughout the environment.

Many of India’s early artistic images portray its environment’s abundant fertility:4

- A linga is a phallic statue that’s supposed to be swelling with the energies that infuse the universe, generate vegetal growth, and encourage human and animal births. Heinrich Zimmer wrote that the phallus was a common symbol in the Harappan civilization, which flourished between 2600 and 1900 BCE. Linga cults are still common in India, Nepal, and large areas of Southeast Asia.

- Nagas, according to Zimmer, were also honored in remote antiquity. They’re mythical serpents that dwell in and guard rivers and ponds. Serpents are easily associated with abundant fertility. They flow like water by slithering and shedding their skins whole. People also associate them with the earth’s power to engender vegetal growth, because they penetrate the ground and emerge like a plant. Their long, tubular forms and sliding, undulating motions make it easy for folks to associate them with sex. In many ways, they represent nature’s mysterious procreative energies.

- Zimmer said that tree worship was already ancient when the story of the Buddha meditating under a pipal tree and attaining enlightenment spread. Pipal, banyan, and fig trees have been highly honored in India. All have especially copious root and branch systems, and their profuseness is easily associated with an abundant universe full of life-giving energy.3

- Zimmer wrote that mythical nature spirits called Yakshas were already popular in ancient India. They live in hills and trees, and guard precious jewels and metals. By the late first millennium BCE, people in much of India honored them, and many still do, associating them with prosperity, fertility, water, and protection.4 Ancient Indians made lots of terracotta statues of them. The females have rounded bodies and large breasts and hips, and they undulate as though they’re dancing. Vegetation often surrounds them. Plentitude, the growth of plants, and motion thus mesh in these images so that they’re easily associated with the bountiful flow of energy from the universe’s initial unity.

This mixture lived on in some of the most famous early Buddhist stupas (mounds that contain relics of the Buddha and of deceased religious dignitaries). The four high entrance gates at the main one at Sanchi brim with sculpture of floral motifs and dancing women. The stupa at Amaravati (in the southern province Andhra Pradesh) was covered with scenes of curvy human bodies that were densely packed, and which moved like foliage blowing in the wind. The religion that says that life is full of suffering and which proclaims that we must sever our attachments to the world emerged in an older field of meanings that was so immersed in abundant life that people sometimes expressed these ideas in its terms.5

So ancient Indians made many images that expressed nature’s dramatic gushes (what A.L. Basham called intense vitality6). They did this in many media. These art works and the natural landscapes probably strengthened people’s assumptions that reality is basically a profuse and unified flow of energy which is so bountiful that it flouts the proportioned forms that ancient Greeks resonated with and embodied in their sculpture, ceramics, painting, and temple architecture.

In The Speaking Tree, Richard Lannoy wrote that one of the main characteristics of Indian art is the appearance that all human, animal, vegetable, and mineral forms derived from the same substance.7 He felt that temples and other buildings look as though they grew from the soil. In contrast with the static and perfect forms of Greek temples, many traditional Indian buildings seem to be integrations of all forms and beings into a single energy, and this energy is in perpetual motion.

One of my favorite experiences of this architecture was at Mahabalipuram, which is about 45 miles south of Chennai. The Pallava Dynasty, which ruled much of southeastern India from the sixth century CE to the ninth, carved a 152-foot-long frieze on a cliffside in the seventh century. It either represents a story from the Mahabharata in which Arjuna (Krishna’s student in the Bhagavad Gita) practices austerities to persuade Shiva to give him a weapon called the pasupata, or it’s about the descent of the Ganges River, which originally flowed up in the sky. In the latter story, the ocean had dried up and all the gods, people, animals, and plants were withering. A saint named Bhagiratha practiced austerities to bring the Ganges to earth, but the river was so powerful that it would have split it. The saint was able to convince Shiva to let it fall onto his head so that it would cascade from his hair.

The cleft in the middle of the frieze is possibly where the river would have flowed down to earth. Nagas undulate in the middle of it, and creatures ranging in size from elephants to rats face it. Several features of the frieze thus support the second interpretation. But whether Pallava kings used one tale or the other, or both, they illustrated it with an abundance of life forms, from a cat and rodents at the bottom to celestial beings in flight at the top. All are in motion, and they’re integrated within an animated field which includes an enormous variety of species in the universe’s flows of energies.

Near this frieze, I spotted a baby goat scratching its side against a three-foot-high ancient stone statue of a monkey. As soon as I pointed my camera at them, two girls (one about six and the other about four) scooted next to the statue and posed. I often experienced this dense integration of life forms from different species and eras in India.

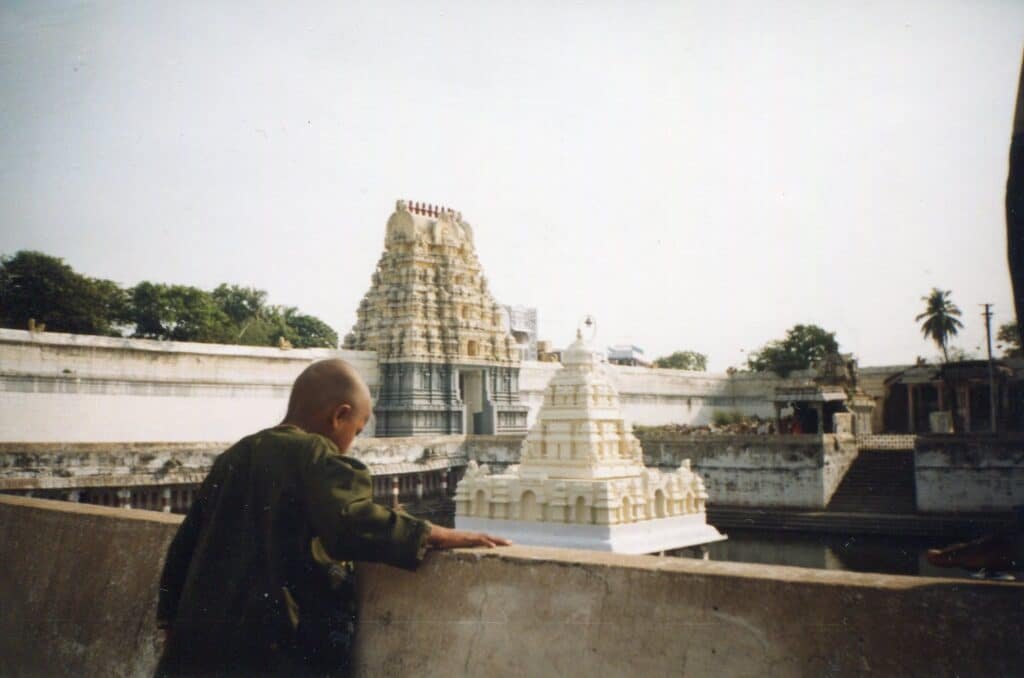

In Bangalore in 1996, I was walking through a temple compound with a high gopura (gate tower) that had many levels of carved gods while the whole area was enveloped by dragonflies slowly floating around. Their gossamer wings glistened in the afternoon sun. The countless thousands of delicate flying creatures and the abundant forms on the temple seemed to mesh into a limitless field of shimmering energies. The dragonflies’ relaxed speed made the abundance feel gentle and all-embracing.

The historian Stanley Wolpert wrote that everything exists in India, usually in magnified form.8 Things are not merely how they appear on the surface; they seem to be manifestations of a much vaster energy. Fans of Western art sometimes say that they lack the exquisite proportions of the Parthenon, but the liveliness of their environment can inspire as much wonderment and give as much pleasure as you join all other life forms and revel in its vibrancy.