During the Axial Age, in the mid-first millennium BCE, some of humanity’s most influential teachers lived, mental horizons in the West, the Middle East, India, and China expanded to more lands, and ideas were more regularly shared across borders. People often looked for basic principles to comprehend all this novelty and uncertainty with. But attempts to completely define all of nature fostered schools that didn’t get along with each other. “My concept of truth is the best, and you’re educated to the extent to which you agree” became dominant in discourse. People began to shoehorn nature and thought into different ideologies, disciplines, and religions. Each often became its own horizon–each claimed to completely own its subject matter. To know something in one way often precluded knowing it in other ways. Assuming only one foundation of thought as valid drew deep fissures between ideas that are compatible with it and all other ideas and modes of experience.

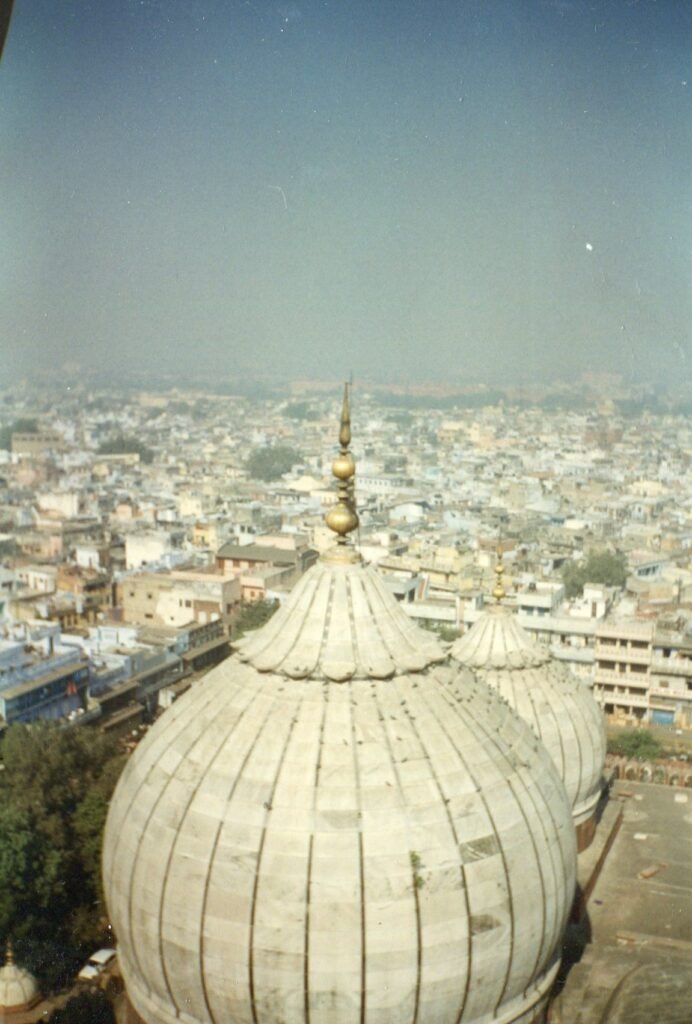

But pause between the feeling that the universe is unified and wanting to grasp the most basic principles that the unity is based on. Look Beyond, and see the beauty in another world-view, for example Islamic culture. The delicate patterns on the inside of a Mosque’s dome reflect the idea that all nature has been created by God, and all these patterns revolve around the center of that dome, as all nature and humanity revolve around God. Five times every day, the members of the House of Islam face Mecca in this spirit. Nature is unified, and all of its lifeforms submit to the infinitely glorious god who created it.

The Maqaam in music also reflects this, as dozens of sequences of scales are patterned in ways that resemble circles, stars and polygons Different points in these shapes are correlated with astronomy. All these scales are thus part of a larger cosmic unity, as the Islamic community is, and as the forms inside a Mosque’s dome are. The oud (below) is played throughout the Middle East, and some music theorists there felt that it has healing abilities. I can see how people can believe that, since its soft tones and light body make it seem to send caressing vibrations through the body.

This sense of unity is also reflected in the first statement that a believer proclaims: La ilaha illa Allah—there is no god but god. Though not all cultures’ mainstreams would agree that this is the prime statement from divinity about itself (for example, the Upanishads say tat tvam asi—that art thou–divinity is not distinct from creation), we can appreciate the sense of unity in this statement and how it reflects many aspects of Islamic civilization. The Arabic statement has an alliteration and rhythm that make it feel as though it’s the totality, just as a dome, the facing of Mecca, and the Maqam are. All these modes reflect each other in a world-view whose richness can be beautifully contrasted with linear perspectives that the West has emphasized, including three-dimensional perspectives that Florentines articulated in the 15th century.

Look Beyond again and explore an equally rich cultural landscape. Thai culture, like many in Southeast Asia, often prefers to avoid absolutes. A lot of Buddhists in Thailand would find the contentiousness of the three great religions from the Middle East harsh and uncouth. Harmony, gracefulness, politeness, and the enjoyment of the moment are where the unity of society and nature hang together. Thai architecture, sculpture, and painting portray some of the most graceful curves and pleasing colors imaginable.

The most exemplary geometry is not as linear as it was for ancient Greeks; it’s conceived more in terms of grace. It emphasizes what is pleasing and what fosters polite behavior that promotes harmony in society and nature. Thai architecture, sculpture, and painting have the same avoidance of blunt surfaces that people usually prefer in behavior.

One of the prime manifestations of divinity is rice. The earth becomes pregnant, and from her comes the food that sustains people and the social harmony. Some traditional Thai thought has seen food as one of the five basic elements! This might not be one of the most accurate ideas from physicists’ perspectives, but it might be one of the happiest, and one that easily interweaves with the focus on politeness, graceful forms, Buddhist merit, and the enjoyment of the moment.

Some historians have noted that this emphasis on graceful forms is ancient. Dhida Saraya noted that the Dvaravati civilization began to flourish more than 1,500 years ago in the southern part of the Chao Phya basin. This civilization was an association of cities and villages that mixed people of many ethnic groups and formed trading relationships that extended to India and into lands in modern Burma and Cambodia, and which adapted Buddhist and Hindu art and ideas from India. They adapted several Indian styles, from the Guptas, Amaravati, the Pallavas, and the Ajanta caves. Saraya noted that the Dvaravati synthesized all these influences and ethnic groups in a relatively tolerant society and a sense of grace. This tolerance and synthesis of several ethnic groups and artistic styles into cultural patterns that have emphasized grace and the enjoyment of the moment also characterized later Thai societies (such as Sukhothai, Ayutthaya, and early Bangkok), and these patterns have thus been reinforced as mainstream.

Look Beyond yet again. Many African cultures value vibrancy over static definitions, and they see the community as the prime locus of unity. To place everything under one system of definitions would take the vitality out of living. According to some anthropologists, a lot of thought patterns are organized around rhythm, sound, and touch, and thought is not as dominated by vision or abstraction as it is in the West.

Now look With, and if you have identified with the West, the static forms and ratios that it has often emphasized can become even more beautiful. I stood in front of the Parthenon in Athens, admiring the balance in its refined forms, and they became increasingly luminous as I compared them with other cultures’ ideas of balance. All places reflected each other as I stood in front of Athena’s home.

See how the world begins to shine? If you’re more oriented to motion than vision, see how cultures around the world can dance with each other in limitless ways? Doesn’t’ it seem that each way of perceiving has so far only seen a miniscule part of the whole, and that there is limitless potential for adding richness to perspectives?

As you continue to combine looking At, With, and Beyond, these three modes keep enhancing each other’s capabilities by enabling you to be increasingly open to new perspectives. And they bring out more aspects of all cultures. They also encourage people to see more types of connections in nature and to imagine ways that different cultural patterns can mix.

The historian of religions Karen Armstrong wrote that the Axial Age’s leading teachers emphasized higher standards of ethics, which extended to all people rather than to only members of one’s tribe or network of family and friends. As looking At, With, and Beyond grow together, people’s horizons can continuously open, and this can increase compassion for others. They can also appreciate living systems ever more deeply.

So we are at the threshold of an Axial Age that can immensely eclipse the previous one. The internet and today’s regular contact between cultures allow us to expose and share wonders to degrees that the past Axial Age could not have imagined, if enough people become inspired to make the effort.