The first time I arrived in Bangkok, it seemed to have its own logic—or illogic. Gleaming skyscrapers were unevenly spread among low-rise apartments, single-family homes, and golden temple roofs and spires. The winding streets looked haphazard. I could see why many Westerners find this city enigmatic. There were no linear perspectives of enough of the whole to give me an idea of how the place ticks. The densely packed mishmash of buildings and undulating streets suggested a different way of thinking.

Bangkok is a fairly new city, even newer than Silicon Valley’s San Jose. It was founded in 1782, after Burmese armies had sacked the wealthiest and most politically powerful Thai city, Ayutthaya, in 1767. The horrors of the sack made old traditions seem like a lost haven. The siege dragged on for more than a year and ended in Burma’s ruthless destruction of the city. its dreamscape of golden spires collapsed into heaps of burnt bricks.

Siam was orphaned—she had no king, court, or capital. The sudden scarcity of food split up families. Many monks were unable to eat and had to disrobe and find employment in the lay world. People even ransacked wats’ libraries for cloth that had protected the hallowed scriptures.

A charismatic military leader named Taksin then drove out the Burmese, who had gotten into a war with China which they had to divert resources to. He also moved the capital south, to the other side of the river from where modern Bangkok would soon rise (pictured below). This area was closer to the sea and thus to international trade routes. Thais could more easily buy arms and escape if the Burmese invaded again.

Taksin is a complex figure for Thais. They admire him as a great general, but after taking the throne, he believed that he was a divinity. He forced monks to worship him and demoted those who refused. Taksin had hundreds flogged and forced into hard labor. French missionaries wrote that he spent his time praying and fasting in order to be able to fly. His conduct was especially disturbing to Thais because many believed that the impiety of Ayutthaya’s elites had brought the old kingdom down. He was a tremendous general, but while on the throne, he and the noble families who led society lacked empathy with each other. Thais needed a ruler who embodied the best aspects of their past but got one who represented a world out of joint.

The people rebelled against the tax farmer of Ayutthaya for being especially rapacious. Because Taksin had appointed him, locals associated them with each other. The officer that the court sent to quell the uprising joined it and called for Taksin’s overthrow. The rebellion met little resistance, the old nobles spearheaded a palace coup, and the great fighter who saved Siam during its darkest hour was executed.

Thais then invited a man who had distinguished himself on the battlefield to be the king. Chaophraya Chakri reigned from 1782 to 1809 as Rama I, and he was the first in the Chakri Dynasty. Recently deceased King Bhumibol (honored below) continued the line as Rama IX.

The new king immediately started to rebuild his country. After only one month on the throne, he moved the capital across the river to its current location on the east bank. Burma also had a new monarch and seemed ready to pounce again—the east side was easier to defend. It would launch another invasion in 1785, which the Thais rebuffed. The Chakri Dynasty’s prestige grew.

Rama knew that the old traditions were political unifiers. He thus continued associations between the monarch and Vishnu (the universe’s preserver), which Angkor Wat’s builder and Ayutthaya’s kings had projected. Since the mythological Rama was an incarnation of Vishnu, the king wrote a Thai version of the Ramayana and organized performances of it. The palace sponsored troupes of dancers who dramatized it. This tradition still thrives; the kids below were rehearsing for a performance.

Rama also quickly strengthened the monkhood and ensured that the most pious and educated led its hierarchy. He built several monasteries in Bangkok and brought hundreds of old Buddha statues to them from Ayutthaya and Sukhothai. Because many animistic cults and rituals had grown into Buddhist practices during Ayutthaya’s history, Rama sponsored a grand council to establish a definitive corpus of Buddhist scriptures. He also had several Theravada works translated into Thai from Pali. For the lay world, he revived state ceremonies from Ayutthaya. The new monarch tried to revitalize the past and purify it from the decadence which he felt had weakened Ayutthaya.

Bangkok’s three central building complexes brilliantly reinforced Thai traditions as the new city developed. They have combined into a characteristically Thai concept of space. One is the Grand Palace, which stands next to the river and projects a shimmering skyline of golden spires (below).

The second, Wat Pho (it’s more formally known as Wat Phra Chetuphon), spreads out immediately south of the palace so that it continues the ethereal forms.

Wat Arun (above) is the third, and it rises directly across the river. It’s dominated by a lofty stupa which begins as a broad base and steadily becomes narrower until it seems to dissolve into the heavens. In the midst of today’s smoldering traffic and concrete sprawl, this structure seems to radiate enduring grace.

These three monuments have provided exemplary forms in the city’s heart. Rising within sight of each other, their towers flow together as people walk, boat, and drive by. Their lilting and glowing interplays straddle the river as it carries elegant boats. So the old traditions of creating infinitely varied flows of graceful shrines, slow processions, and water from Ayutthaya, Sukhothai, and Lan Na thrive in the big city. As in older Thai art, perspectives meander through slowly moving forms and images. While grids of straight streets in many Western cities give you a big perspective of the whole and allow you to analyze it from an abstract distance, Bangkok’s three central monuments immerse you in a field that seems gentle and ethereal. Streets are often smoggy, congested, and loud, but this core of sacred buildings opens views into enchanted landscapes.

I stepped into a boat to cross the river for a closer look at Wat Arun (above). Many long and narrow vessels taxied between both sides and between ports on the east bank. For a humongous city bisected by a river, Bangkok has few bridges—Thais still seem psychically connected to boats on waterways. Four monks in orange robes boarded and sat next to me. Their repose and rippling gowns blended with the breezes and gentle water as we slowly approached the wat.

Wat Arun presides by the dock. This masterpiece soars over 200 feet, and it’s surfaced with white stucco and covered with pieces of broken porcelain shaped as flowers with sinuous lines and long points.

They add speckles of bright red, yellow, and green to its surface.

Four smaller spires surround the central tower, and the contrasting heights make it appear even taller and broader. The below photo shows one of them from the central spire.

Wat Arun is both otherworldly and monumental, and since it balances heaven and earth while rising from the rippling waters, it integrates all domains. Many Bangkok residents consider it their favorite temple in the city.

Back on the other side of the river, I headed for the palace (the above shot shows it from Wat Arun). Amulet sellers spread their wares on tables and mats over long stretches of sidewalk that run north from the palace.

Locals wear some of them on chains for good luck, and the assortment I saw was huge.

Buddha statues, Hindu gods, phalluses, and portraits of the king and holy men flickered together as spritely as Wat Arun’s porcelain. Customers often choose a certain amulet for a specific need. Some buy the phalluses for fertility, and many of these charms bear inscriptions that are supposed to increase their potency.

Amulet shoppers clogged the sidewalks into gridlock, showing that animistic beliefs are alive and well in the modern city.

A plain white wall encloses the palace and conceals splendors that people could never imagine from the street. The first courtyard that visitors enter is a large rectangular open space. On the left is the entrance to Wat Phra Kaew, which houses the hall of the Emerald Buddha, Thailand’s most revered statue.

A large cloister with a mural of the Ramayana surrounds the hall. Its scenes of court life are so numerous that I felt that the Chakri Dynasty was making a political statement.

Kings sit in front of gilded halls and pavilions with steep gabled roofs, and courtiers kneel before them in sparkling golden gowns.

These elegant gatherings seem like the height of civilization. They dramatically contrast with battle scenes, giant monsters, and animated natural landscapes.

The new monarchy seems to have been distinguishing its own goodness from dangers outside of its embrace. This courtly refinement was the standard that would safeguard the new country.

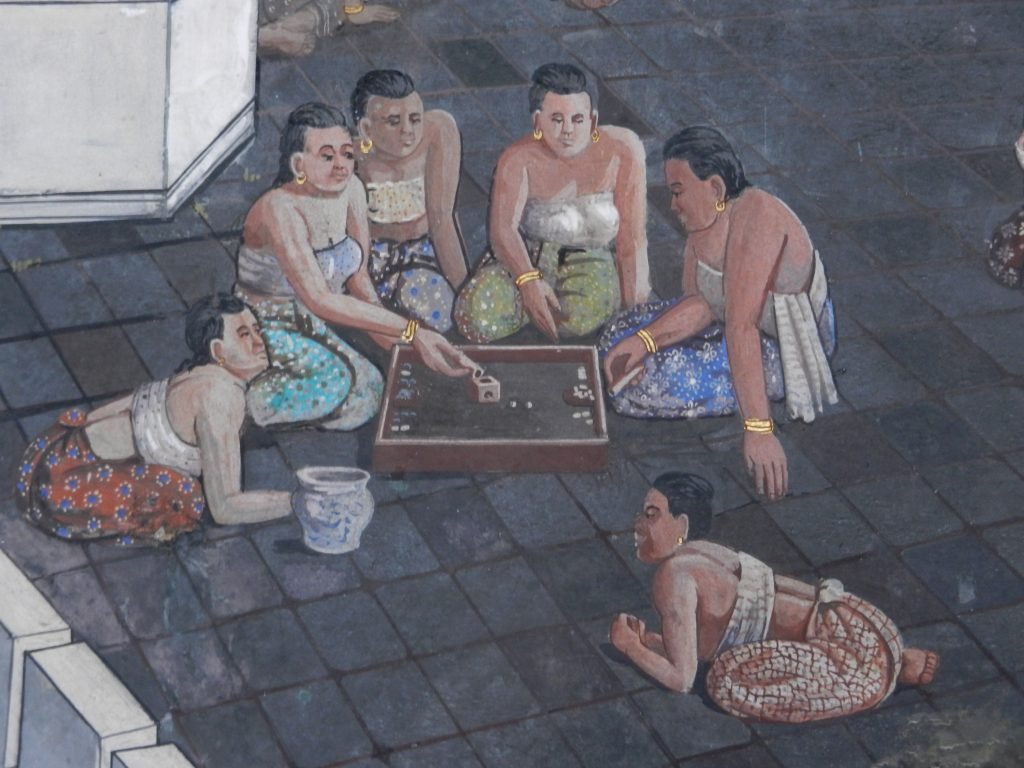

Some scenes lighten the seriousness with images from ordinary life.

Women bathe, a man buys fruit, a boy rides a water buffalo’s back, and a deer drinks from a pond covered with lily pads. Like the Buddha, the royal court rules gently.

Thais especially venerate the Emerald Buddha. King Rama I installed it in Bangkok in his drive to restore traditions, and it is supposed to have magical powers that protect the country.

I found the Emerald Buddha hard to see. It’s a little over two feet tall but it sits on a lofty gilded throne in a long hall (the above shot is of a replica up in Chiang Rai). Far more noticeable than the Buddha’s features was the dense crowd of Thais paying homage. They quietly lined both sides of the hall and slowly proceeded through, perhaps hoping to receive some of the statue’s grace. It is clothed in an outfit that matches each of the three seasons (hot, cool, and wet), and the king and his family have changed it in solemn ceremonies—only they can touch this statue.

The Emerald Buddha has a legendary past. It was sculpted from jade or jasper quartzite in the earthy Lan Na style and discovered in a wat in Chiang Rai in 1434 when lightning struck a stupa that encased it (pictured below).

People thought it had miraculous powers, and they took it to a succession of northern Thai temples until the Laotian king Setthathirat carried it to his kingdom in the 16th century. It remained in Laos until the Thais conquered much of it during Taksin’s campaigns, and they brought it back to their own realm. This story and tales of other Buddha statues’ journeys to different temples have circulated in Thailand, helping to ingrain these sculptures into people’s traditional ideas of geography. Many of the most revered statues have been copied several times, and the power of the original has been ritually transmitted into the newer statues, which were set up in other temples, including the one in Chiang Rai. When I visited it, it was housed in its own building, presiding in a tall pavilion on a high platform, and both were decorated with gold filigree to maximize the statue’s dignity. Eminent Buddha statues form a field of grace, and their benevolent energies help keep the kingdom in order.

The Emerald Buddha is thus associated with many concepts that have been dear to Thais, including etiquette, ritual, the Buddha’s compassion, and the political center as a space that radiates positive energies. Rama I linked royalty with these ideas by installing the statue at the palace and enacting ceremonies to care for it. He masterfully combined many ideas from the past with the new monarchy and city.

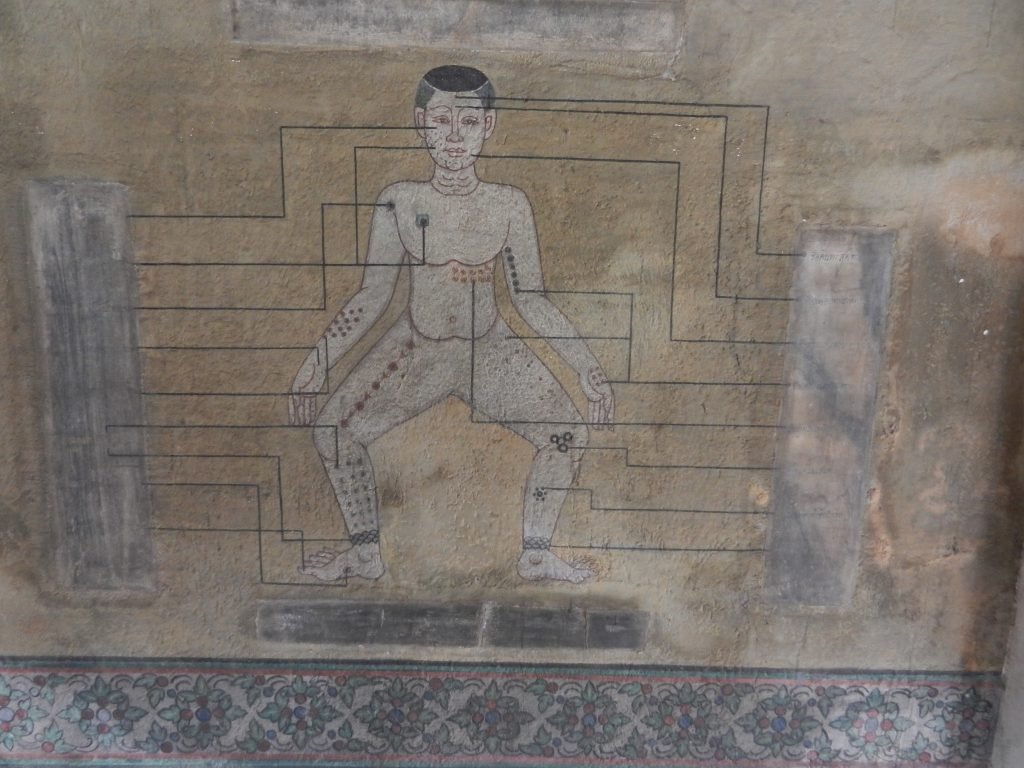

Thailand’s heritage glows as much at Wat Pho. In the early 19th century, King Rama III spread time-honored Thai knowledge by establishing this wat as a key center of education in religion, astrology, traditional medicine, and literature.

People who went there found a wealth of old Thai art forms as examples of what harmonizes the world. Four tall and narrow stupas punctuate it, and each honors one of the first Chakri kings. The spires flicker with inlay and a different color dominates each one (blue, red, yellow, and silver). About 70 smaller stupas which house the ashes of other royals surround them. This group grounds the Chakri line in the old forms of narrow and sinuous towers that seem to dance as you walk around them. But one of Wat Pho’s forms especially stands out.

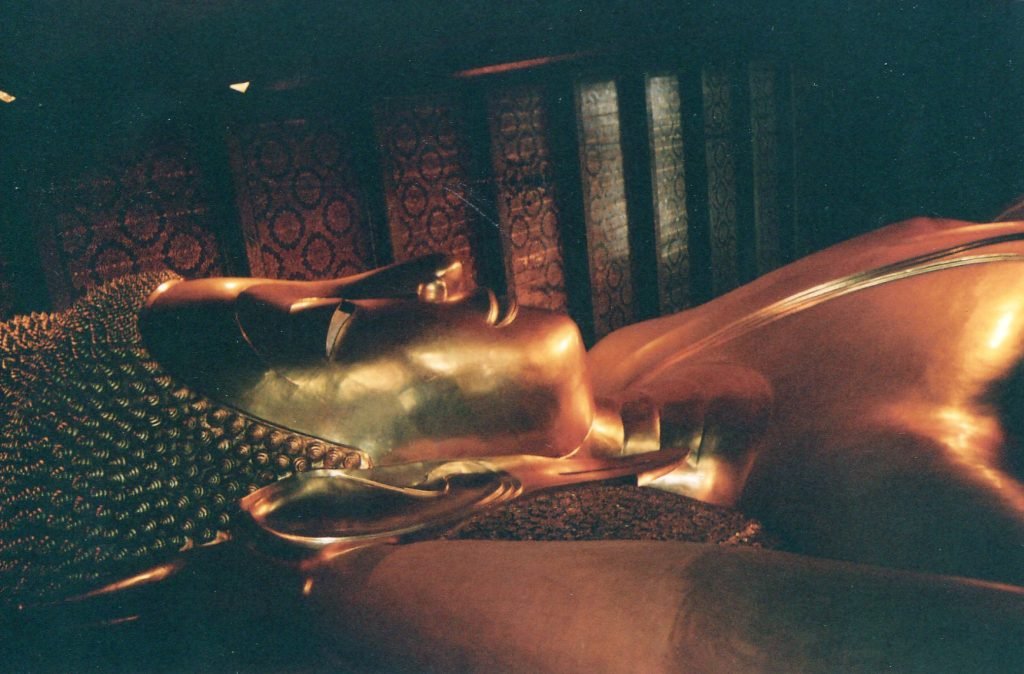

A sleeping Buddha that is 150 feet long and 50 feet high resides in one of Wat Pho’s halls. This is one of the most popular Buddha postures in Thailand. Wat Pho’s statue is one of the smoothest-looking monuments I’ve ever seen. Although it’s enormous, the lines delicately curve and the gold leaf that covers it makes them appear as soft as silk.

The soles of its feet contain an artform that deserves its own article.

Bangkok’s first kings used several ideas to restore the past as people recovered from the Burmese invasion. Statues, footprints of the Buddha, wats, the royal court, paintings and performances of the Ramayana, rivers, and old aesthetics centered on gentle and animated flows reinforced Thailand’s ancient heritage. The city sometimes boils and festers, but people are still often reminded of their traditions.

All these places surrounded people and made up a common perspective of the world as Bangkok became increasingly modern.

More skyscrapers keep mushrooming up, but boating on the river makes them seem more playful than Manhattan’s or Chicago’s.

And many locals are quick to get in the spirit.

Staying in Bangkok or the rest of Thailand shows that space is more than an abstract three-dimensional grid. Interactions that are both graceful and fun make space meaningful. Many Thais become uncomfortable with mechanical regimentation and excessive seriousness. No wonder why a lot of Western visitors decided to move there.